Overview

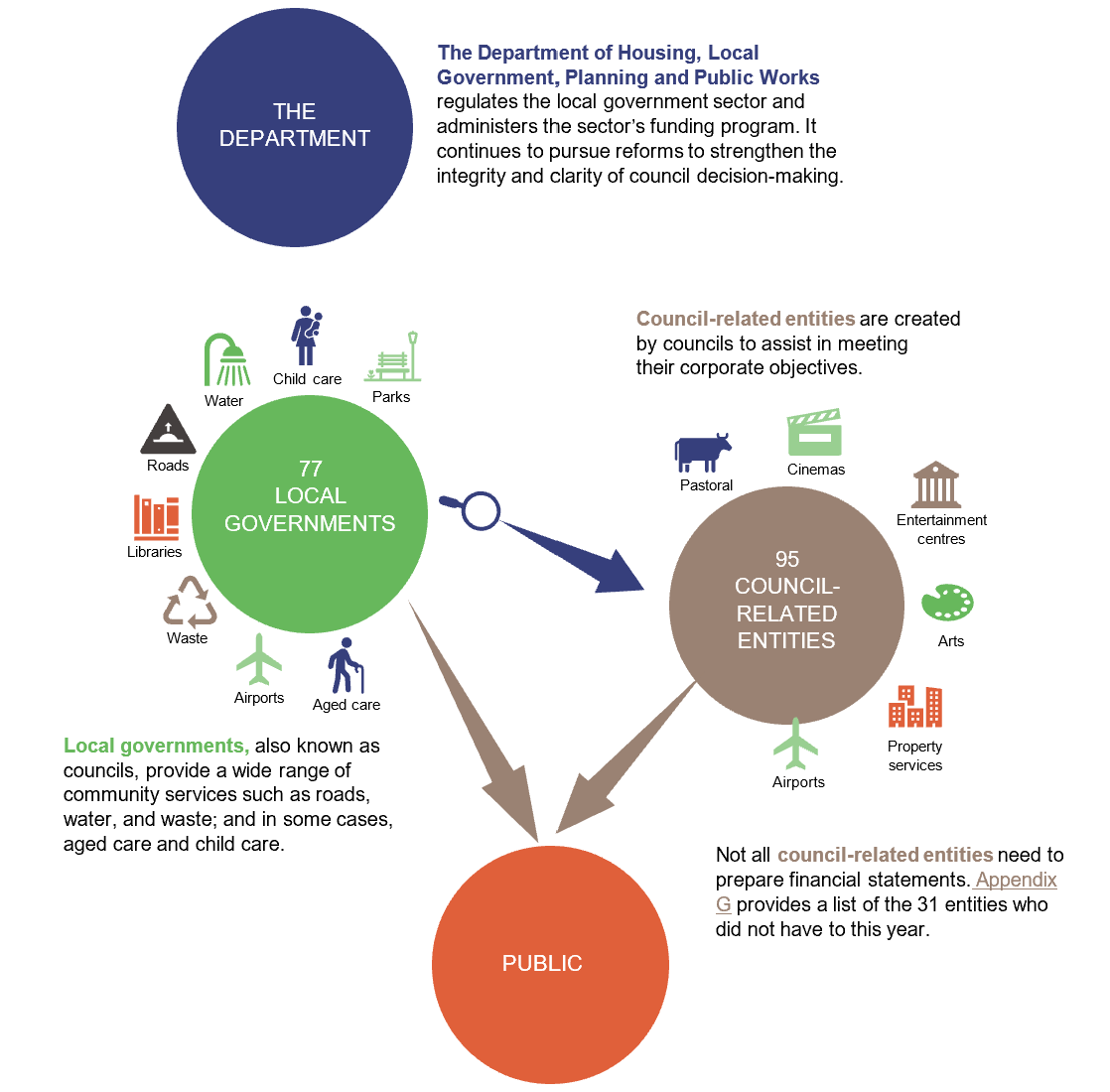

Queensland's local governments, also known as councils, are the first line of connection to our communities. They provide Queenslanders with crucial services such as roads, water and waste, animal management, parks and libraries, and they conduct town and land planning. They have an important role in supporting the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of their communities.

Tabled 29 January 2024.

Report on a page

This report summarises the audit results of Queensland’s 77 local government entities (councils) and the entities they control.

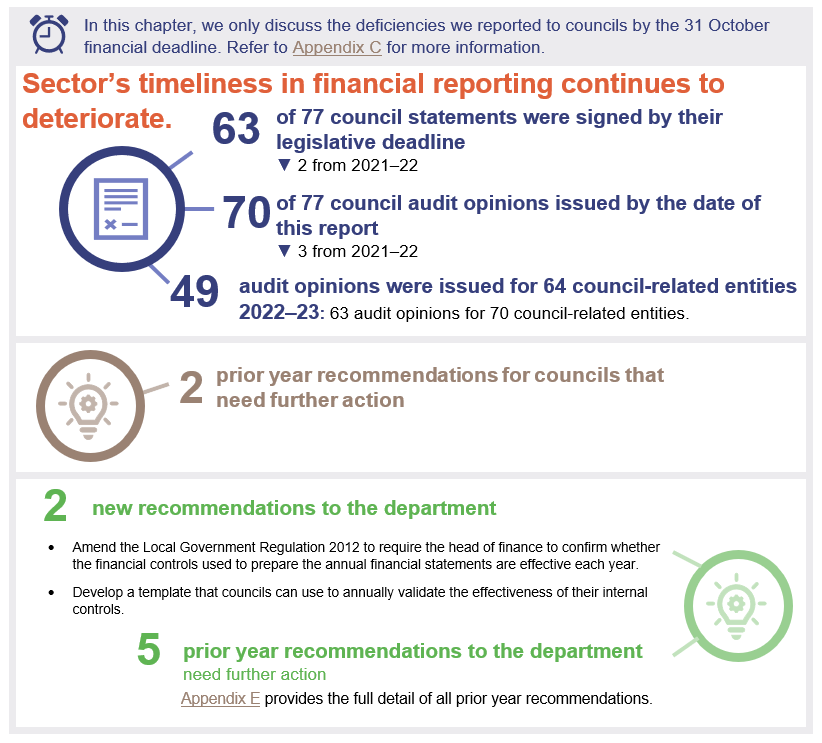

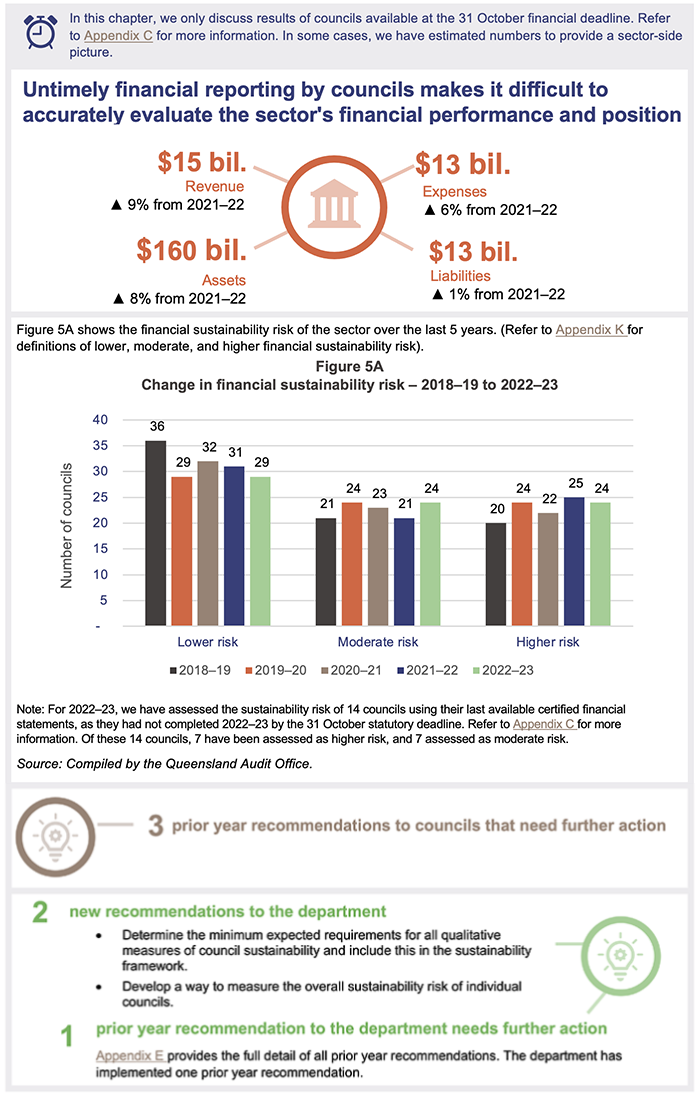

Financial statements are reliable, but less timely

Communities need timely financial information to evaluate their council’s performance – especially when local government elections occur. The next election is on 16 March 2024. Despite this, 14 councils did not complete their 2023 financial statements by their 31 October statutory reporting deadline, and 7 of these councils have still not completed them as at the date of this report.

Of the 14 councils that did not complete their financial statements by 31 October 2023, 10 of these have also missed the deadline in at least 2 of the last 3 years.

Poor accounting practices are the primary driver for councils not being able to complete their financial statements in a timely manner. Being able to attract and retain skilled staff also contributes. Having the right skills and capability in key positions and a strong framework for financial controls would help councils mitigate financial and operational risks.

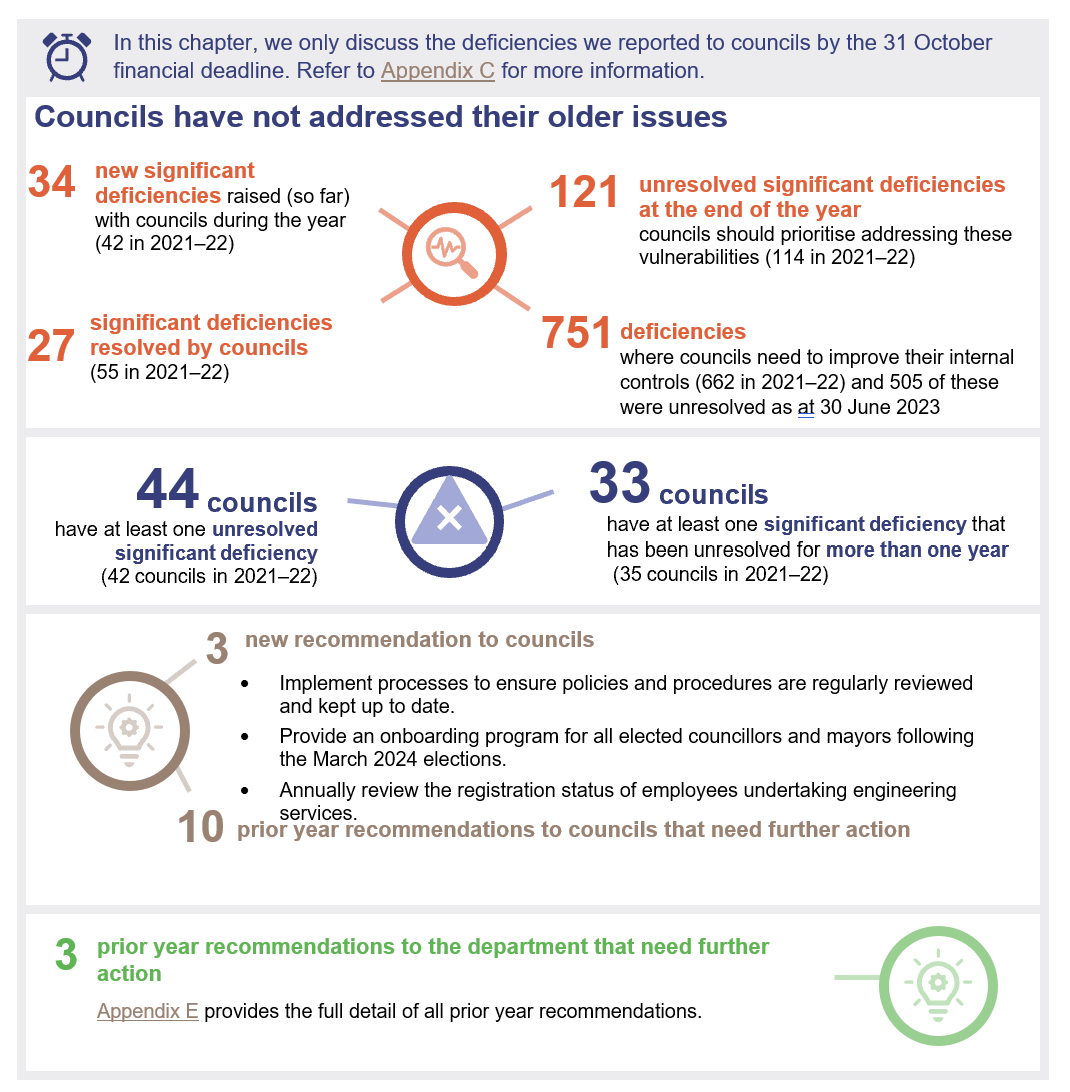

More action is needed on outstanding high-risk issues

There are still 121 unresolved significant (high-risk) issues (2022: 114) at councils. This will increase as we finalise the audits of the 14 councils who failed to meet the statutory deadline. We continue to see a greater proportion of long-outstanding issues in councils that do not have an audit committee or internal audit function.

Councils face many external threats in their day-to-day operations, including cyber security. Yet two-thirds of the sector still has weaknesses in the security of its information systems, and 24 per cent of councils have not provided cyber security training to their staff.

Having good policies and procedures would help councils mitigate some of these external threats. However, 34 councils (2022: 25 councils) either do not have some of their policies and procedures in place, or they are outdated and not relevant to their operations anymore. As a result, some councils may have difficulties transitioning any newly elected members or staff into their organisation.

Having extra advance funding continues to affect results

For the second year, councils have received more of their (federal) financial assistance grants for the next year in advance, and reported this as revenue (as required under accounting principles). Despite this, 24 per cent of the 63 councils that had completed their financial statements by 31 October generated operating losses, and over half would have made losses without the extra funding they received.

Councils need good budget and cash management processes to handle their increasing costs and cope with changes to the timing of grant funding, which is outside of their control.

New sustainability measures are in effect, but the risk framework needs improvement

At 30 June 2023, 48 councils (2021–22: 46 councils) are still at either a moderate or a high risk of not being financially sustainable. The department’s new financial sustainability framework is in place for the 2024 financial year. However, the associated risk framework can be refined to more clearly define how it will help the department, communities, and councils, evaluate a council’s overall financial sustainability risk.

1. Recommendations

Recommendations for councils

This year, we make the following 3 recommendations for councils.

|

Implement processes to ensure policies and procedures are regularly reviewed and kept up to date |

|

1. Councils should regularly review and update their policies and procedures to ensure they are up to date and meet the needs of their operations. Each council should develop a work plan to ensure all policies are reviewed at least every 3 years or when there are significant changes to the council’s structure (Chapter 4). |

|

Provide an onboarding program for all elected councillors and mayors following the March 2024 elections |

|

2. Councils should educate all elected councillors and mayors on matters that are specific to their council, including unique challenges of their council and its strategic objectives and operations. This will ensure there is a smooth transition to the new council. It should also reinforce their understanding of their responsibilities and encourage mayors and councillors to work effectively together and with council staff (Chapter 4). |

|

Annually review the registration status of employees undertaking engineering services |

|

3. Review the registration status of employees undertaking engineering services to make sure they are complying with the Professional Engineers Act 2002. Councils should do this on an annual basis (Chapter 4). |

Councils need to take further action on prior year recommendations

Recommendations that were outstanding in Local government 2022 (Report 15: 2022–23) are summarised in the following tables.

Our recommendation for councils to improve their month-end and year-end financial reporting processes is no longer applicable. This is because it is superseded by our recommendation for councils to reassess the maturity of their financial statement processes and implement improvements.

|

Theme |

Summary of recommendation |

Local government report |

| Governance and internal control |

Assess their audit committees against the actions in our 2020–21 audit committee report (Chapter 4) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

Use our annual internal control assessment tool to help improve their overall control environment (Chapter 4) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

|

Improve risk management processes (Chapter 4) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

|

Have an audit committee with an independent chair. Audit committee members should understand their roles and responsibilities and the risks the committee needs to monitor (Chapter 4) |

Report 13: 2019–20 |

|

|

Establish and maintain an effective and efficient internal audit function (Chapter 4) |

Report 13: 2019–20 |

|

| Asset management and valuations |

Include councils’ planned spending on capital projects in asset management plans (Chapter 5) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

Review the asset consumption ratio1 in preparation for the new sustainability framework. Assess whether the actual usage of assets is in line with asset management plans (Chapter 5) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

|

Improve valuation and asset management practices (Chapter 3) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

| Financial reporting |

Reassess the maturity levels of financial statement preparation processes in line with recent experience to identify improvement opportunities that will help facilitate early certification of financial statements (Chapter 3) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

Enhance liquidity management by reporting unrestricted cash expense ratio2 and unrestricted cash balance3 in monthly financial reports (Chapter 5) |

Report 15: 2021–22 |

|

| Information systems |

Strengthen the security of information systems (Chapter 4) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

Conduct mandatory cyber security-awareness training (Chapter 4) |

Report 13: 2019–20 |

|

| Procurement and contract management |

Assess the maturity of their procurement and contract management processes using our procure-to-pay maturity model, and implement identified opportunities to strengthen their practices (Chapter 4) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

Enhance procurement and contract management practices (Chapter 4) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

|

Secure employee and supplier information (Chapter 4) |

Report 13: 2019–20 |

1 Asset consumption ratio measures how much of council’s infrastructure assets have been used compared to what it would cost to build new assets with the same benefit to the community.

2Unrestricted cash expense ratio measures how much money council has available for its regular expenses and unexpected financial needs.

3 Unrestricted cash balance is the cash reported by a council that is not set aside for specific uses or obligations.

Implementing our recommendations will help councils strengthen their internal controls for financial reporting and improve their financial sustainability. We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix E.

Recommendations for the department

This year, we make the following 4 recommendations to the Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works (the department).

|

Introduce an internal controls assurance framework for councils |

|

4. Amend the Local Government Regulation 2012 to require the head of finance to confirm whether the financial controls used to prepare the annual financial statements are effective each year. The confirmation should be provided to the mayor and chief executive officer each year before they sign the financial statements and should include:

5. Develop a template that councils can use to annually validate the effectiveness of their internal controls. This will help councils and heads of finance identify their key financial internal controls and determine whether these controls have operated effectively throughout the year. The department may benefit from Queensland Treasury’s help, and using practices that are already in place in the state sector (Chapter 3). |

|

Determine the minimum expected requirements for all qualitative measures of council sustainability and include this in the sustainability framework |

|

6. Amend the sustainability framework for Queensland councils to:

This will give councils a clear understanding of the qualitative elements they are being assessed against, and will help councils prioritise actions to improve them (Chapter 5). |

|

Develop a way to measure the overall sustainability risk of individual councils |

|

7. Develop a methodology to determine the overall sustainability risk of councils. The methodology should assess the ratios in the department’s sustainability framework in combination so an overall financial sustainability risk profile can be determined for each council. The methodology should also consider the impact on the overall financial sustainability if any of the benchmarks (identified for each ratio in the sustainability framework) are not met. This will help the department prioritise its resources for councils or groups of councils that need attention more urgently than others. It will also help councils understand what good looks like and how the department intends to use the ratios in total to assess the financial sustainability of councils (Chapter 5). |

The department needs to take further action on prior year recommendations

The department has made some progress in addressing the recommendations we made in our prior reports.

It has published a framework to assess the sustainability risk of councils. However, further action is still required for 9 recommendations, as summarised below.

| Theme |

Summary of recommendation |

Local government report |

| Governance and internal control

|

Require all councils to establish audit committees (Chapter 4) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

Make sure all councils have an effective internal audit function (Chapter 4) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

| Financial reporting and capability within the sector

|

Provide training to councillors and senior leadership teams around financial governance (Chapter 3) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

Measure the effectiveness of training programs provided to councils (Chapter 3) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

|

Provide training on financial reporting processes and support councils in meeting their reporting deadlines in times of need (Chapter 3) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

|

Provide necessary guidance and tools to councils to help improve their month-end financial reports (Chapter 3) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

|

Provide a clear definition of ‘extraordinary circumstances’ for councils seeking ministerial extensions to their legislative time frame for financial reporting (Chapter 3) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

|

|

Financial sustainability |

Provide greater certainty over long-term funding (Chapter 5) |

Report 17: 2020–21 |

|

Information systems |

Develop a strategy to uplift capability of the sector on cyber-related matters (Chapter 4) |

Report 15: 2022–23 |

We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix E.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to all councils and the department. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

2. Overview of entities in this sector

Queensland Audit Office.

3. Results of our audits

This chapter provides an overview of our audit opinions for the local government sector.

Chapter snapshot

We express an unmodified opinion when financial statements are prepared in accordance with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards.

We issue a qualified opinion when financial statements as a whole comply with relevant accounting standards and legislative requirements, with the exceptions noted in the opinion.

We include an emphasis of matter to highlight an issue of which the auditor believes the users of the financial statements need to be aware. The inclusion of an emphasis of matter paragraph does not change the audit opinion.

Audit opinion results

Audits of financial statements of councils

As of the date of this report, we have issued audit opinions for 70 councils (2021–22: 73 councils). Of these:

- 63 councils (2022–23: 65 councils) met their legislative deadline

- 4 councils (2022–23: 2 councils) met the extended time frame granted by the Minister for Local Government (who may grant an extension to the legislative time frame where extraordinary circumstances exist)

- 3 councils (2021–22: 2 councils) that had their financial statements certified past their legislative deadline did not receive an extension from the minister.

At the date of this report, we are waiting confirmation from the minister’s office of the status of extensions of 3 councils. In 2021–22, 4 councils that received ministerial extensions did not meet their extended time frame.

Figure 3A shows the councils that did not have their financial statements certified by their 31 October legislative deadline.

Most of these councils are based in rural and remote areas where the challenge of attracting and retaining appropriately qualified and experienced finance staff is exacerbated. This when coupled with high turnover in finance staff and lower financial statement maturity levels (refer to Appendix J) has made it difficult for these councils to produce quality financial statements to have their audit completed in a timely manner.

Timely completion of the audit of the financial statements relies on both the auditors and council meeting the time frames that are mutually agreed at the start of the audit process. These agreed timelines are placed at risk when there is a delay in the provision of key deliverables to the auditors and/or when auditors are not able to process the key deliverables in a timely manner stemming from the delay in receiving key deliverables. When these agreed time frames are not met, the financial statements certification is delayed, and in some instances the legislative time frames are not met.

| Councils that did not meet their 31 October legislative deadline | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2022–23 financial statements not yet complete because 2021–22 financial statements not yet certified | |

|

|

|

|

1 These 10 councils have not completed their financial statements within their statutory deadline in at least 2 of the last 3 financial years.

2 Although these councils did not meet the 31 October deadline this year, they had their financial statements certified by the date of our report.

Queensland Audit Office.

Seven councils have not provided their communities with current, reliable financial information

When we published this report, 7 councils had not finalised their 2022–23 financial statements – including 4 councils that had not finalised their 2021–22 financial statements. Heading into the March 2024 local government elections, these 7 councils have not provided current and reliable financial information to their communities.

This means their communities cannot evaluate the financial health of their councils and see where public money has been spent.

If these financial statements are not finalised by the election, the 2022–23 financial statements will become the responsibility of the newly elected council.

Financial statements are reliable

The financial statements of the councils and council-related entities for which we issued opinions were reliable and complied with relevant laws and standards.

We issued a qualified opinion for 2 council-related entities – Local Buy Trading Trust (controlled by the Local Government Association of Queensland Ltd) and the Wide Bay Burnett Regional Organisation of Councils Inc. This was because these entities were unable to provide the auditors with enough evidence that the revenue they recorded was complete. We issued a qualified opinion for Local Buy Trading Trust last financial year for the same reason.

We included an emphasis of matter in the audit opinions for 5 council-related entities because:

- 3 were reliant on financial support from their parent entities

- 2 had decided to wind up their operations.

Not all council-related entities need to have their audits performed by the Auditor-General. Appendix G provides a full list of these entities.

Status of unfinished audits from previous years

When we tabled Local government 2022 (Report 15: 2022–23) in June 2023, some councils and council-related entities had not finalised its financial statements for previous years.

At the date of this year’s report:

- Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council had completed its 2020–21 financial statements and received a qualified opinion. This was because it was unable to provide enough information about its lease and motel revenue for us to confirm its revenue was correctly reported.

- Central Highlands (QLD) Housing Company Limited’s 2021–22 financial statements were certified and received an unqualified opinion with an emphasis of matter because the directors decided to cease trading and enter voluntary liquidation.

- Mackay Region Enterprises Ptd Ltd and Whitsunday ROC Limited both had their 2021–22 financial statements certified and received unmodified opinions.

In Appendix I, we have included a list of other councils and council-related entities that have still not completed their financial statements from previous years.

More councils are not prioritising financial reporting

In recent years, we have reported that councils are becoming less timely in completing their financial statements, meaning the information they provide to the public is not current or relevant.

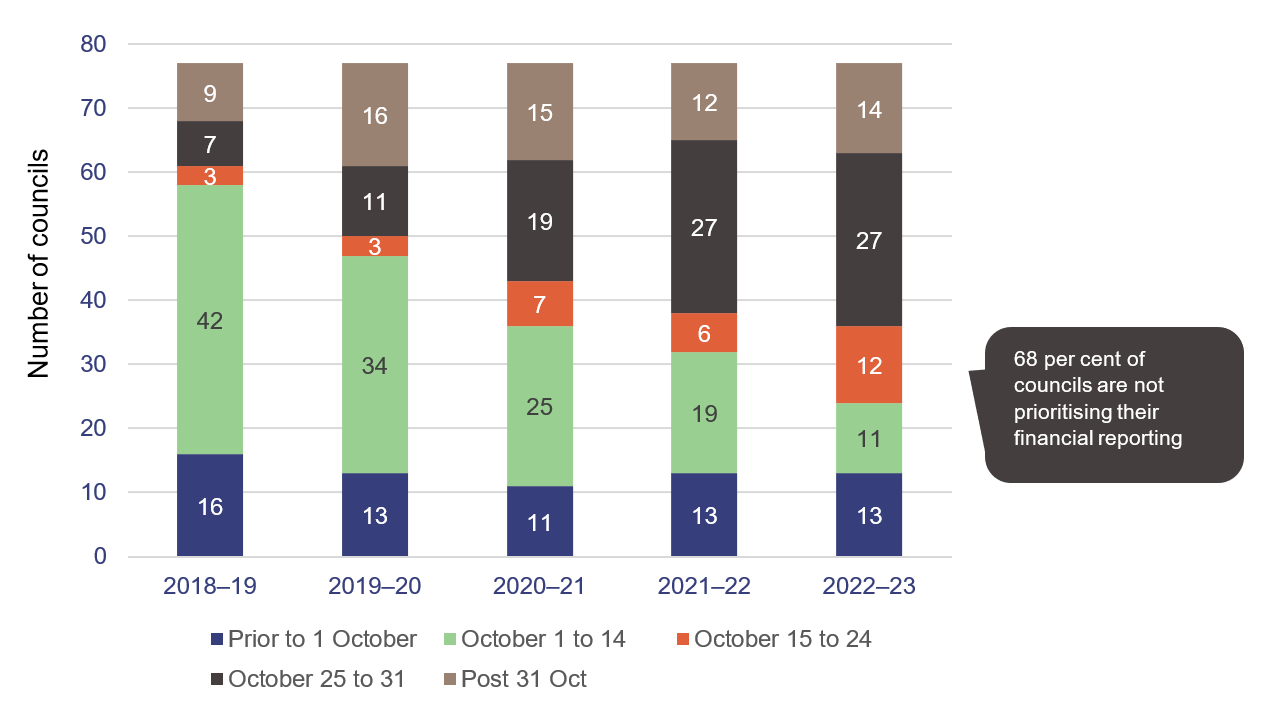

For the last 2 years, roughly half the sector only completed its financial statements in the last 2 weeks before the deadline or missed the 31 October statutory reporting deadline altogether, as shown in Figure 3B. This is a significant decrease from 2018–19 when fewer than 25 per cent of councils were this late completing their financial statements.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

The 31 October deadline for statutory reporting should be considered as a minimum standard rather than the target date to have financial statements completed. Councils should be aiming to bring forward their financial reporting, so their financial statements are completed by early October at the latest. This allows some contingency time should unexpected delays be encountered.

When councils finalise their financial statements very close to the legislative deadline, it puts significant pressure on their finance teams, auditors, and audit committees. This often compromises the quality of the financial information, and increases the risk of errors.

It reduces the time available for councils and audit committees to review financial information and also requires us to complete our audits in very short time frames. In combination, this significantly reduces the time for vital quality control activities and impacts the ability for councils to appropriately consult on key issues.

Timely financial reporting is not just important for financial statements. Without it, management and councillors do not have reliable financial information to help prepare the next year’s budget, and may be making financial decisions based on inaccurate or out-of-date information.

The delayed financial reporting timelines also extend to when councils seek ministerial extensions. As stated earlier, the Minister for Local Government (the minister) may grant an extension to the legislative time frame for certification of a council's financial statements, where extraordinary circumstances exist.

Of the 14 councils that applied for an extension to have their 2022–23 financial statements certified:

- 2 applied after the 31 October statutory deadline

- 10 councils applied for extension in October, of which 7 did not apply until the last week of October

- 5 applied for more than one extension this year

- 6 of the 14 councils also applied for an extension last year.

Nine councils have applied for an extension in 2 of the last 3 years. Four of these 9 councils have applied for an extension in each of the last 3 years:

- Etheridge Shire Council

- Gympie Regional Council

- Mornington Shire Council

- Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council.

In Local government 2022 (Report 15: 2022–23), we recommended the department provide a clear definition of 'extraordinary circumstances'. Our view remains that when councils – and many times the same councils – seek extensions from the minister year after year, it cannot be deemed ‘extraordinary circumstances'.

Factors such as natural disasters and the lack of a skilled workforce contribute to untimely completion of financial statements across the sector each year.

However, the main reason councils do not complete their financial statements in a timely manner is that they have poor processes for financial reporting.

The sector has not improved its processes for financial reporting

In 2020–21, councils self-assessed their financial statement preparation processes using our financial statement maturity model – available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/better-practice.

When we compared these self-assessments to each council's ability to achieve early financial reporting (by 15 October) we concluded that 22 councils had overstated their maturity levels.

Because of this, in Local government 2021 (Report 15: 2021–22), we recommended all councils reassess their maturity levels in line with their recent financial reporting experience. Only 63 per cent of the sector implemented our recommendation.

This year, we assessed the financial statement maturity levels of each council ourselves (see Appendix J for details).

Each council’s desired level of maturity will differ – recognising what might be required for a council in a large city may not necessarily work for a smaller council in a regional town. However, because councils have had stable business models without restructures for more than 10 years, they should be able to at least reach an ‘established’ maturity level.

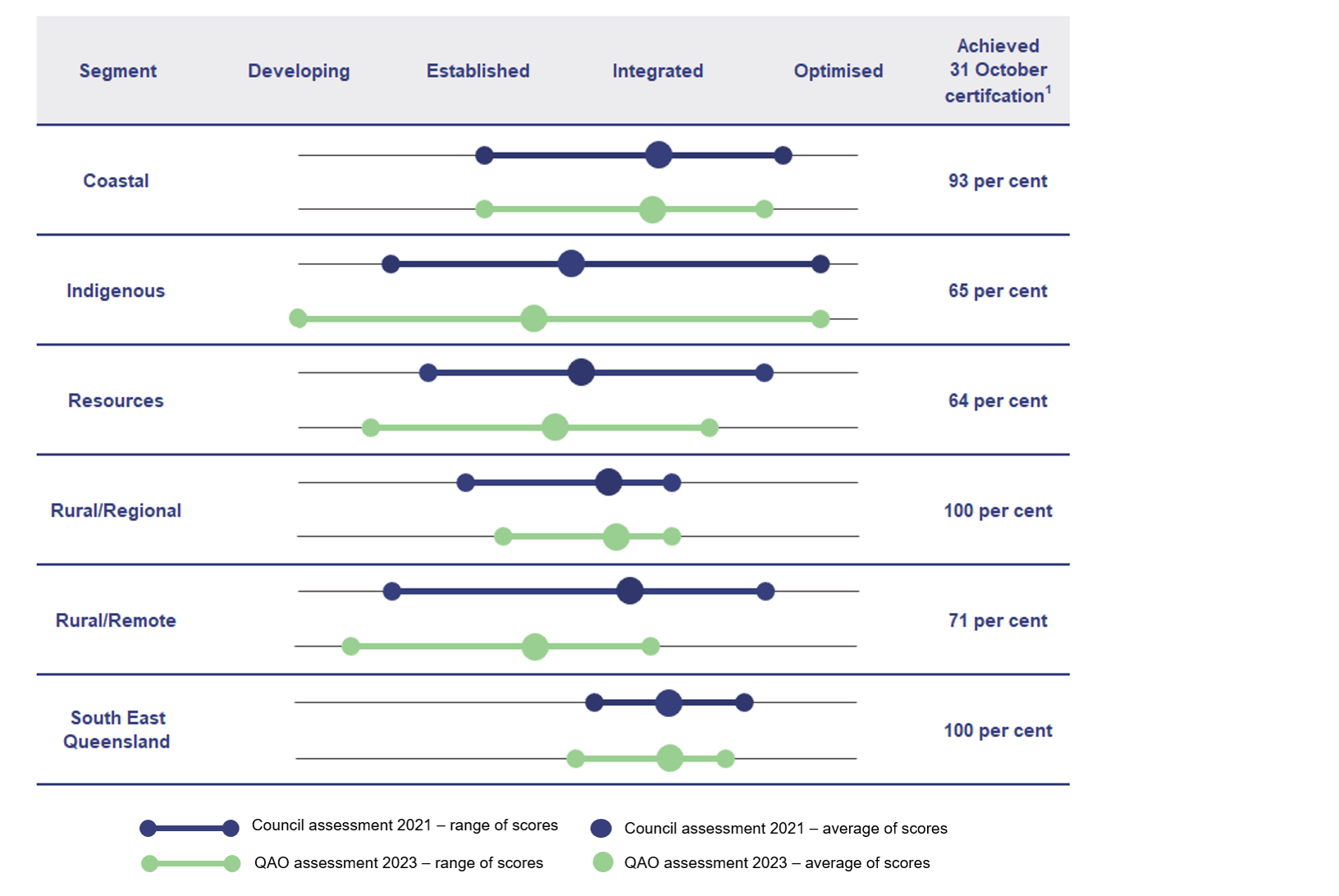

In Figure 3C, we show the maturity levels for the sector at a segment level (as defined by the Local Government Association of Queensland – refer to Appendix B). It shows the results of councils’ self-assessments from 2021 compared to the audit assessments we performed this year.

Note: This graph shows the minimum and maximum score for each component of the model, and the average of all scores. Individual scores for each council vary.

1 Percentage of councils within each segment that had their 2022–23 financial statements certified by 31 October 2023.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office, based on information collected from council self-assessments (2020–21) and QAO assessments (2022–23), using our financial statement preparation process maturity model.

We use 4 levels of maturity, which we define as:

- developing – an entity does not have key components for effective financial reporting, or they are limited

- established – an entity shows basic competency for financial reporting

- integrated – an entity’s financial reporting practices are fundamentally sound, however some elements could be improved

- optimised – an entity is a leader of best practice for financial reporting.

Overall, we found no significant change in the maturity of financial reporting practices at 45 councils (60 per cent) compared to their 2020–21 self-assessment.

However, we noted that our assessment of the maturity of many Indigenous, Resources, and Rural/Remote councils is lower than the self-assessments these councils undertook in 2020–21. This confirms our view that some councils had overstated the maturity of their financial reporting. Councils in these segments also generally have a higher number of deficiencies in their internal controls, and are not timely in their financial reporting.

Both the department and the councils need to take further action to address our recommendations from prior years. These would help councils improve their financial reporting processes. While individual councils should consider their own desired maturity levels, there is room for improvement across the sector as well.

In this next section of this chapter, we discuss the areas in which councils can improve their financial reporting processes.

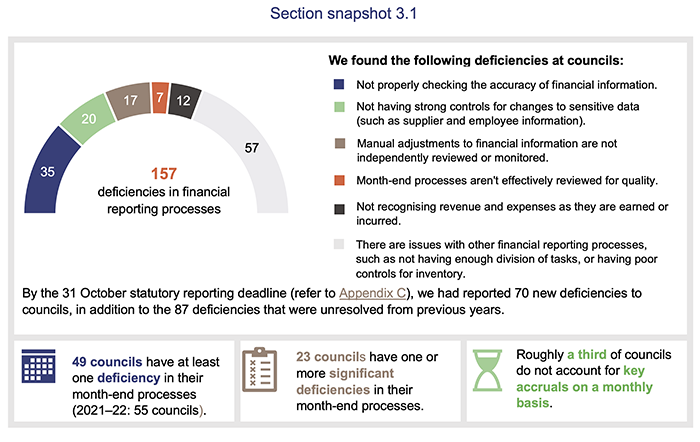

Improving monthly financial reporting process will streamline year-end financial statement preparation

Councils complete processes at the end of each month, and year, to make sure financial amounts are correct for their financial reporting. Examples of strong month-end and year-end processes include:

- checking key financial amounts against supporting documents in a timely manner

- keeping general ledgers up to date

- having staff (independent of those who prepared the month-end financial reports) implementing quality reviews over the reports

- making sure the financial information provided to councillors is complete, by using accrual accounting processes (recognising revenue and expenses as they are earned or incurred, regardless of when cash has been received or paid).

When councils self-assessed the maturity of their financial reporting in 2020–21, they identified that their month-end processes had significant room for improvement. This included 46 councils that did not adopt accrual accounting in their month-end reports. Last year, we gave councils guidance about accrual accounting and how this should be reported in monthly financial reports.

Despite this, we have found roughly a third of councils are still not adopting accrual accounting for their month-end reporting. This means that the monthly financial reports they provide to their elected members and executive staff are not complete and accurate, which could cause councils to make incorrect financial decisions.

Councils whose monthly financial reporting processes are strong, and align with their year-end financial statement processes, find it easier and quicker to complete their year-end reporting processes because:

- errors and issues are generally identified and addressed before the end of the year

- staff are experienced in the tasks required, as these have become part of their routine work each month

- other business areas that the financial reporting teams need information from are familiar with the financial reporting process and time frames.

It is important for councils to regularly evaluate the effectiveness of their internal controls

As well as having strong monthly reporting processes, councils need good internal controls to make sure information used in the financial statements is reliable. It is important they validate that these internal controls have been effective throughout the year.

In the state sector, each financial year – and before management certify the financial statements – Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) at departments need to certify that the department’s financial internal controls are operating effectively. Currently, there is no requirement for heads of finance at councils to provide any assurance to their chief executive officer (CEO) or mayor before they certify their council’s annual financial statements.

Implementing a similar process at councils would improve their financial governance and strengthen their understanding of how effective their internal controls are. This would also provide confidence to the CEO and mayor that the amounts reported in the financial statements are complete and accurate.

|

Recommendation for the department Introduce an internal controls assurance framework for councils |

|

4. Amend the Local Government Regulation 2012 to require the head of finance to confirm whether the financial controls used to prepare the annual financial statements are effective each year. The confirmation should be provided to the mayor and chief executive officer each year before they sign the financial statements and should include:

5. Develop a template that councils can use to annually validate the effectiveness of their internal controls. This will help councils and heads of finance identify their key financial internal controls and determine whether these controls have operated effectively throughout the year. The department may benefit from Queensland Treasury’s help, and using practices that are already in place in the state sector. |

Preparing financial reports requires a wide range of skills

Councils are complex businesses. Preparing their financial statements requires qualified staff with skills that extend beyond knowledge of accounting – including project management, financial management, corporate governance, internal controls, and technology. These skills are obtained through practical experience and through professional qualifications.

As at 30 June 2023, we found more than a third of councils did not have a professionally qualified head of finance. This means they were not accredited by a professional accounting body such as Certified Practicing Accountants or Chartered Accountants Australia & New Zealand.

These councils combined account for 42 per cent of the sector’s unresolved significant deficiencies. This suggests that these councils have weaker internal controls and governance. These councils are also slower to prepare their financial statements – they made up only 25 per cent of the councils who were able to complete their financial statements early (by 14 October) this year.

Some councils spend significant amounts each year on consultants and contractors to fill this skills gap. Although this helps complete their financial reporting each year, it generally does not build capability within their finance teams and does not improve their control environment.

In 2009, the Queensland Government recognised the importance that professional qualifications had on good governance, maintaining effective internal controls, and dealing with complex financial reporting. Because of this, it introduced a requirement that all CFOs of government departments be a member of a professional accounting body.

Where the incumbent CFO did not hold the requisite qualifications, the legislation allowed a transitional period of 10 years for them to undertake the study necessary to meet the minimum requirements.

Implementing a similar requirement in the local government sector would not be simple as councils – especially those outside South East Queensland – find it challenging to attract and retain qualified staff as it is.

But improving financial capability within the sector continues to be critically important for better financial management, enhancing controls to reduce the risk of fraud or error, and more timely financial reporting. Over the years, we have made several recommendations to the department to help lift the financial capability within councils and the need for this uplift continues. A full list of these recommendations and their status is included in Appendix E.

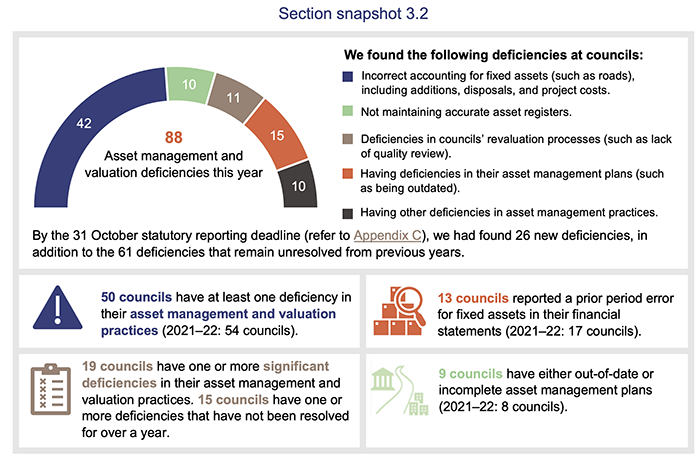

Better asset management and valuation practices will improve asset accounting

In this section, we have identified concerns about the sector’s asset management, asset accounting, and asset valuation processes. These have continued to contribute to untimely financial reporting.

Councils managing their assets better will reduce the number of prior period errors

By the time we compiled this report, 13 councils (2021–22: 17 councils) had recorded prior period errors in their financial statements relating to fixed assets. The number of these prior period errors will increase further as the 14 councils who missed the statutory deadline finalise their financial statements. These errors often contribute to untimely financial reporting.

A prior period error refers to when an entity identifies that there was a significant error in its certified financial statements for the previous year.

Most of the prior period errors we identified related to ‘found’ assets, where councils identified assets they owned that had not previously been reported in their financial statements. The primary reason this happens year after year is because some councils do not reconcile the asset data in their asset system to their finance system – meaning they do not have good asset accounting processes.

Councils should regularly inspect their assets and make sure the information in their financial systems and geographical information systems (which are used to capture, store, and manage detailed components of assets, including their geographical location) agree with each other.

In Asset management in local government (Report 2: 2023–24) we highlighted that:

- only 10 per cent of councils met the minimum requirements of the internationally recognised standard for asset management

- councils have gaps in the way they govern and report on asset management and in how they make sure their asset information is up to date.

That report included 5 recommendations for all councils to help them improve their asset management processes. Councils that have not yet considered our recommendations and developed strategies to address them, should do so.

The sector needs to improve its valuation practices and how it accounts for assets

We have also identified issues in how councils report on assets, including:

- managing valuation processes – when determining fair values (the amounts for which the assets could be sold in a market-based transaction). This includes councils not engaging valuers early enough, providing poor instructions to the valuer, and not adequately reviewing the valuers’ work

- the integrity of fixed assets records – such as maintaining accurate details about assets in their asset register, and physically checking the register is correct and complete.

These issues reduce the quality and timeliness of the financial statements councils produce – often leading to councils not meeting their statutory reporting deadline.

Queensland Treasury’s website (www.treasury.qld.gov.au) contains ‘Non-Current Asset Policies Tools’, which include a comprehensive checklist for revaluations. While these policies do not apply to councils, we encourage council management to consider completing this checklist to strengthen their revaluation processes and make sure they properly evaluate their revaluation process and disclosures.

Councils still need to take further action on 3 of our outstanding prior year recommendations relating to asset management and valuation practices. Appendix E provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

4. Internal controls at councils

We assess whether the systems and processes (internal controls) used by entities to prepare financial statements are reliable. In this chapter, we report on the effectiveness of councils’ internal controls and provide areas of focus for them to improve.

We report any deficiencies in the design or operation of those internal controls to management for their action. The deficiencies are rated as either significant deficiencies (those of higher risk that require immediate action by management) or deficiencies (those of lower risk that can be corrected over time).

Chapter snapshot

Councils are not addressing older issues

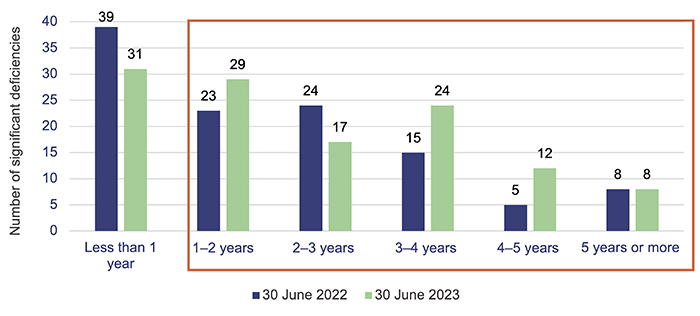

So far this year, we have identified 34 new significant deficiencies across 24 councils (2022: 42 new significant deficiencies). However, we found that the number of unresolved significant deficiencies as at 30 June 2023 had increased to 121 (2022: 114), as shown in Figure 4A.

Although we found fewer new significant deficiencies than last year, this is because we have only included deficiencies reported to councils by the 31 October 2023 statutory deadline. This is so communities can receive our report before the local government elections in March 2024.

The 14 councils that did not complete their financial statements by the statutory deadline have 55 significant deficiencies at this stage. As we finalise the audit of their financial statements, we are likely to raise more significant deficiencies. These will be included in our report next year: Local government 2024.

Queensland Audit Office.

When significant deficiencies remain unresolved for a long time, they may result in one or more of the following risks:

- potential financial loss, including fraud

- increased exposure to cyber related risks, including loss of personal information or disruptions to services

- reputational damage to council

- significant non-compliance with laws and regulations, and internal policies

- material errors in the financial statements.

Because of this, significant deficiencies should be resolved immediately.

However, the number of significant deficiencies that remain unresolved for over 12 months at

30 June 2023 has increased, as shown in Figure 4B.

Queensland Audit Office.

As at 30 June 2023, 33 councils (2022: 35 councils) had one or more significant deficiencies that remained unresolved more than 12 months after we identified it. In Appendix J, for each council, we list the total number of significant deficiencies we found this year, and those that have remained unresolved for more than 12 months.

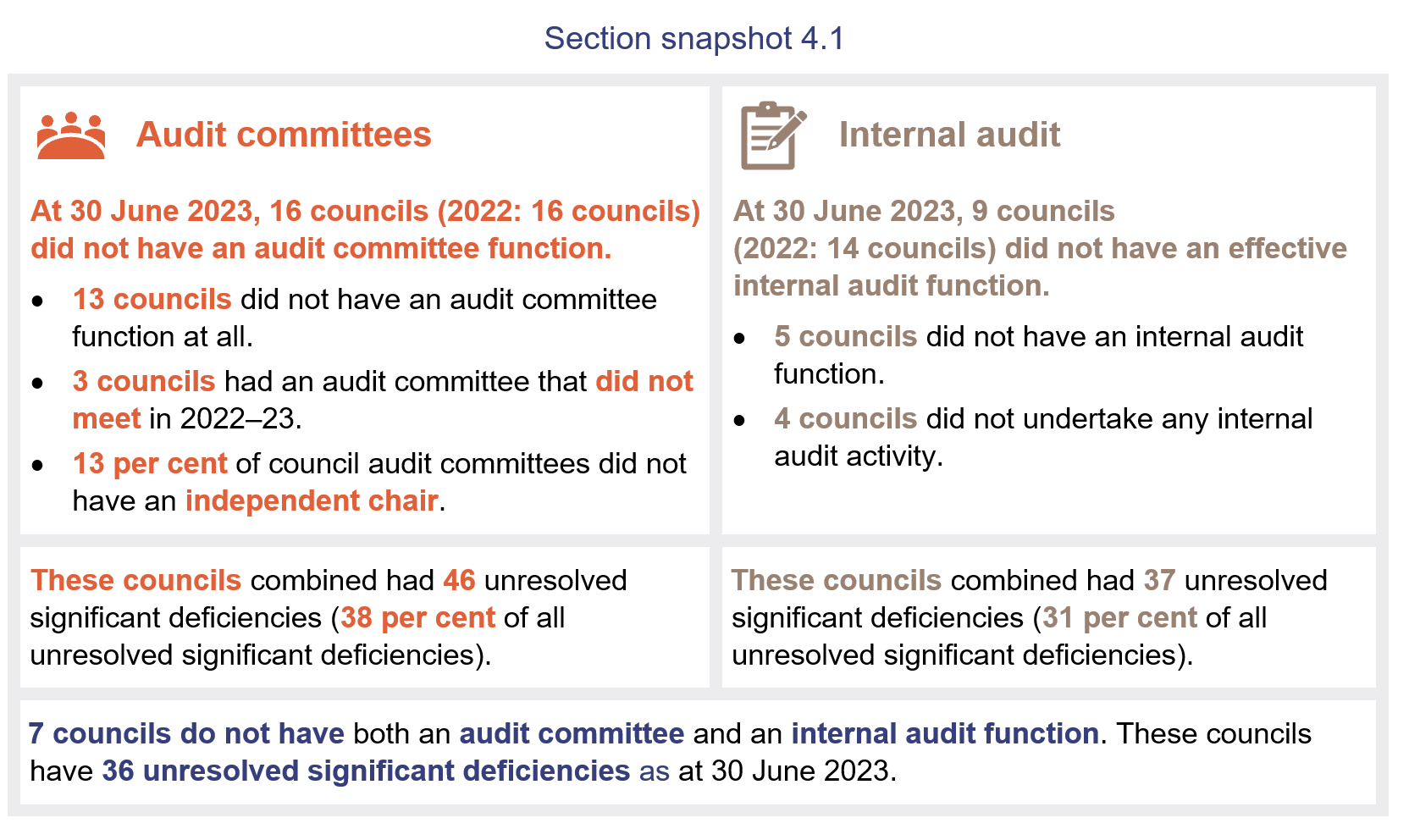

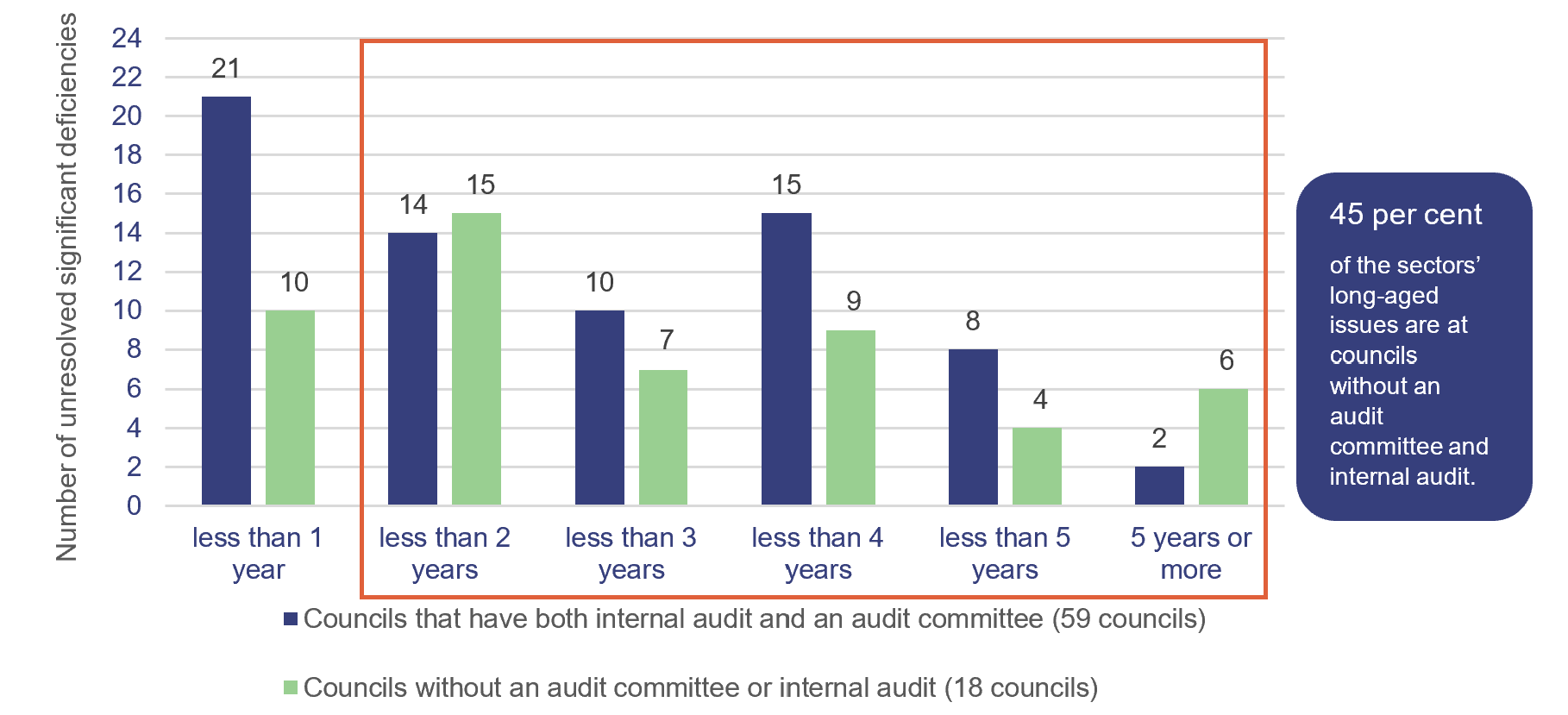

We continue to find the majority of the unresolved significant deficiencies that have been outstanding for a long time are in councils that do not have strong governance structures, such as internal audit and an audit committee.

The sector’s governance is improving, but further action is required

Audit committees and internal audit are crucial components of effective governance within an organisation. These functions work together to make sure internal control deficiencies are resolved in a timely manner.

An audit committee provides council confidence in its financial reporting, internal controls, risk management, legislative compliance, and audit functions. An effective internal audit function provides unbiased view of an organisation’s operations and continuous review of the effectiveness of governance, risk management, and control processes.

To be effective, both functions need to be independent of management. Audit committees with an independent chair and members create a better foundation for robust and incisive discussions and questions.

Figure 4C shows the ageing of issues for councils, grouped by whether the councils have both an audit committee and internal audit function.

Queensland Audit Office.

Having both an audit committee and an internal audit function significantly helps a council reduce the number of long-outstanding significant deficiencies. They oversee proactive and timely resolution of outstanding issues.

The department and the councils have not taken enough action to address our 5 outstanding prior year recommendations regarding council audit committees and internal audit. Appendix E provides a full list of these prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

As identified in our Forward work plan 2023–26, we have commenced an audit to provide insights into the effectiveness of local government audit committees.

Common internal control weaknesses

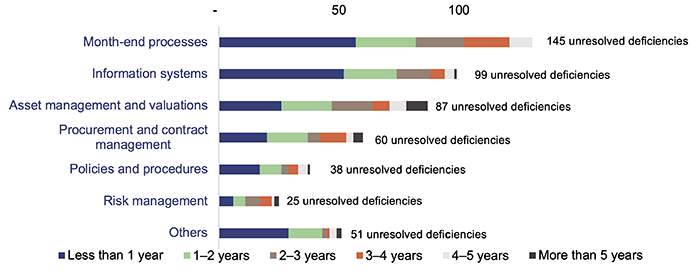

Each year, we find common issues at councils. Figure 4D summarises these weaknesses by the number of years they remain unresolved as at 30 June 2023.

Queensland Audit Office.

We discussed month-end processes and asset management in Chapter 3. In this chapter, we cover the other common internal control weaknesses at councils.

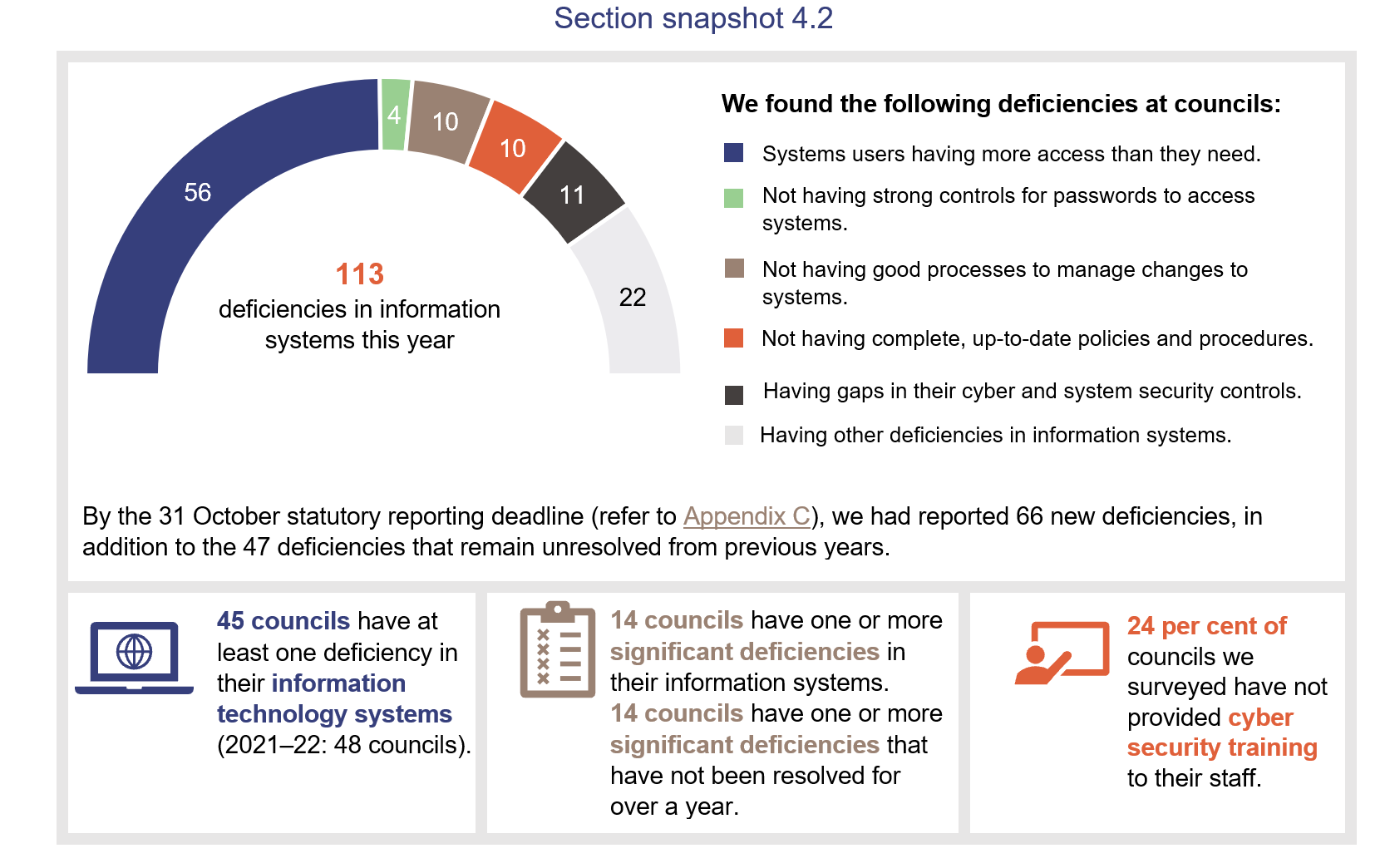

Information systems in the sector are more vulnerable than before

Councils rely heavily on their information systems for their day-to-day operations, yet we continue to identify widespread weaknesses in these systems. So far this year, we identified 66 new weaknesses in how councils secure their information systems.

As cyber security threats increase in number and sophistication, councils must promptly address any weaknesses in their information systems. Councils need to make sure their staff remain vigilant to detect and mitigate threats, prevent human errors, and adapt to evolving cyber risks.

There are 17 councils that have still not developed and implemented mandatory cyber security training for their staff as we recommended 3 years ago. These councils, combined, have 30 deficiencies in their information systems. They may be at a higher risk of cyber attacks than their peers that have provided cyber security training to their staff.

Appendix E provides a full list of our prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

We are finalising a performance audit on insights and lessons learnt on entities’ preparedness to respond to and recover from cyber attacks. We encourage councils and the department to review this report when it is tabled and implement any recommendations relevant to them.

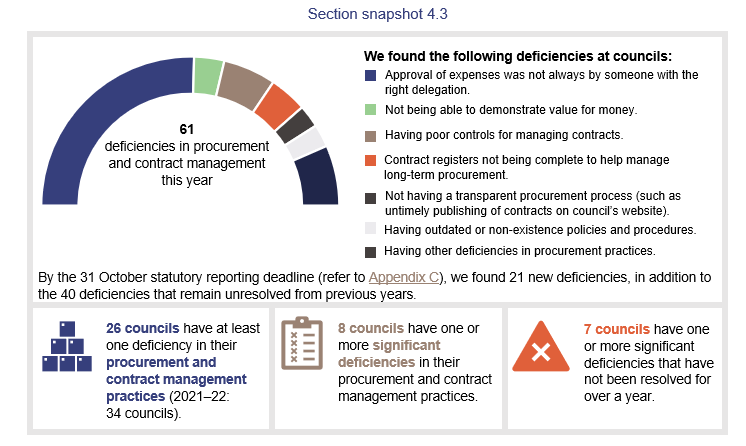

Procurement and contract management processes have deteriorated

Councils spend a substantial amount each year procuring goods and services for their day-to-day operations as well as for maintaining/building community assets (such as roads and buildings). These goods and services are obtained using public money (rates and charges from the community, and grant funding from the state and federal governments).

It is important that councils have appropriate controls in place to ensure they achieve value for money. This includes:

- ensuring purchases are approved by people with the correct financial delegations

- keeping policies up to date and complying with legislation

- having procurement processes that are transparent and give their community confidence no bias exists in the process

- having contract registers that are complete and accurate, to help councils manage long-term procurement.

Our 3 outstanding previous year recommendations in Appendix E remain crucial to make sure councils achieve value for money in their procurement and contract management.

Councils have not prioritised maintaining good policies and procedures

Councils often need to prioritise urgent matters affecting their communities and the services they deliver. Because of this, maintaining their policies and procedures can sometimes become a lower priority.

In recent years, we have noticed an increase in the number of councils that either do not have good policies and procedures, or do not keep them up to date. These councils are exposed to a potential risk of inconsistent practices and poor decision-making, which may result in financial loss, non-compliance with legislation, and inequitable outcomes.

Policies and procedures provide guidance, ensure consistency, assign accountability, and provide clarity to council staff and elected members on how the council operates. Up-to-date policies and procedures help councils make sure they comply with relevant legislation, including the Local Government Act 2009 and local government regulation.

The past 3 local government elections have seen an average turnover in elected members of roughly 52 per cent. There are also changes to executive council staff after these elections. Councils that do not have strong policies and procedures may experience issues as they transition newly elected members and staff into their organisation.

Councils should strengthen their policies and procedures by making sure they are:

- reflective of their values, processes, and day-to-day activities

- easy to follow, in plain language, and align with other policies and procedures, and legislation

- developed and regularly kept up-to-date through a simple and transparent process

- prepared, reviewed, and updated by the staff who are responsible for overseeing them.

Councils should also make sure they have a strong induction process to help any new mayors and councillors understand their responsibilities and the operations of the council and bring them together to work more effectively.

|

Recommendations for councils Implement processes to ensure policies and procedures are regularly reviewed and kept up to date |

|

1. Councils should regularly review and update their policies and procedures to ensure they are up to date and meet the needs of their operations. Each council should develop a work plan to ensure all policies are reviewed at least every 3 years or when there are significant changes to the council’s structure. |

| Provide an onboarding program for all elected councillors and mayors following the March 2024 elections |

|

2. Councils should educate all elected councillors and mayors on matters that are specific to their council, including unique challenges of their council and its strategic objectives and operations. This will ensure there is a smooth transition to the new council. It should also reinforce their understanding of their responsibilities and encourage mayors and councillors to work effectively together and with council staff. |

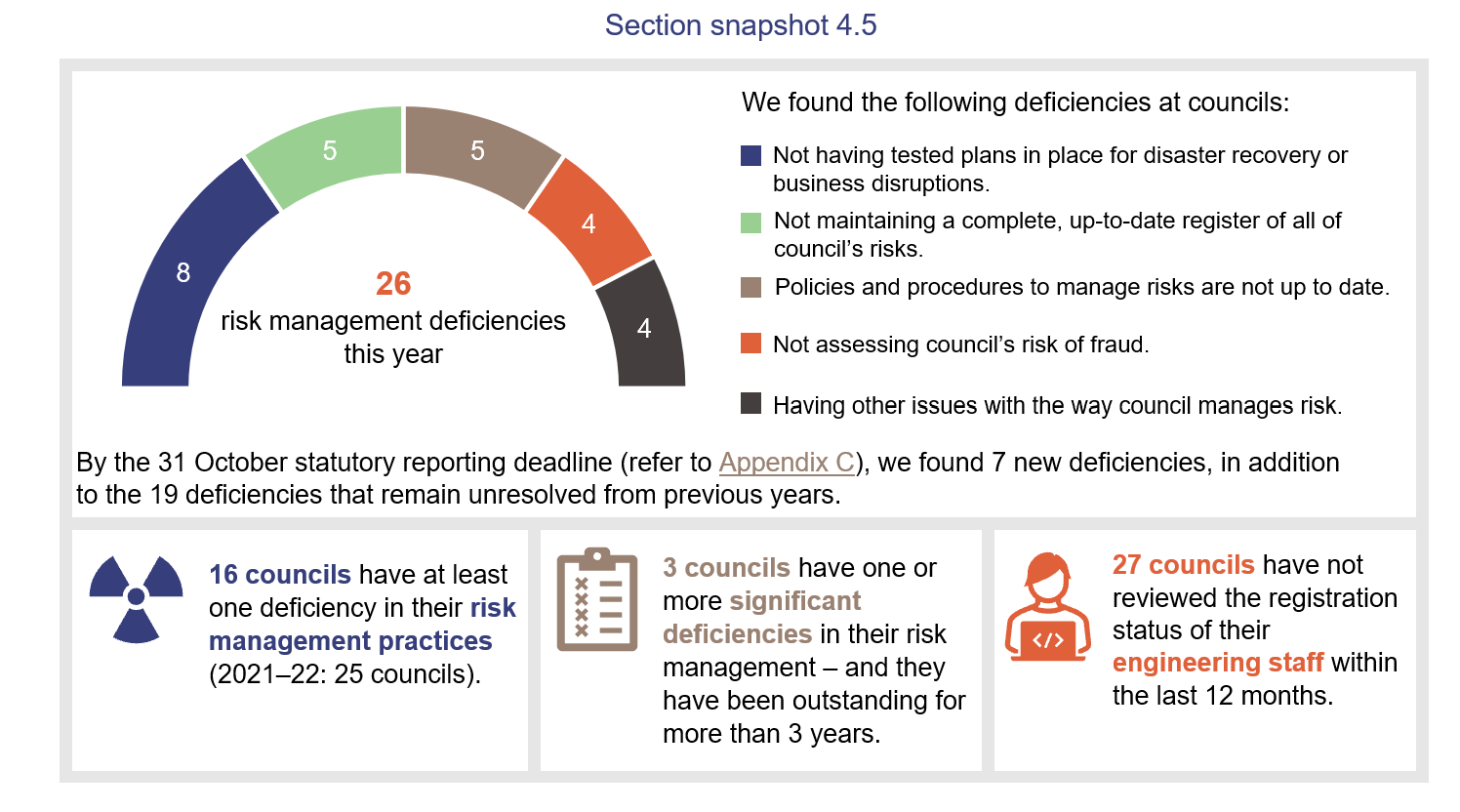

Councils are not keeping on top of the risks they face

Strong and robust risk management practices are more important than ever. Increasing global uncertainty, climate change, threats to supply chains, limited resources, cyber crime, the need for data protection, and privacy concerns are just some of the challenges facing entities. Councils must proactively manage their risks.

Sixteen councils have unresolved control deficiencies relating to risk management, and 8 of these have more than one deficiency in their risk management.

Councils can strengthen how they manage their risk by:

- identifying areas of greatest risk and potential harm

- developing a framework for managing risk and applying it consistently

- developing and implementing a methodology for identifying and assessing risk

- implementing a business continuity and disaster recovery plan and testing it periodically

- establishing an up-to-date risk register.

In Education 2022 (Report 16: 2022–23), we made recommendations for how entities can improve their risk management processes. Councils may benefit from implementing the recommendations made in this report.

We also recently updated our model for assessing the maturity of risk management practices. The model is available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/better-practice. It enables entities to identify the risk management maturity level they want to achieve, and to focus on key areas for development.

Checking that staff are qualified should be part of councils’ risk management processes

In December 2022, the Crime and Corruption Commission (CCC) released a fact sheet about the requirements of the Professional Engineers Act 2022, stating that only a practising engineer can undertake professional engineering services without supervision.

The CCC has stated that council staff in breach of this part of the legislation may be committing corrupt conduct.

This year, we surveyed each council about the qualifications of its head of engineering (who is responsible for carrying out professional engineering services). Based on the responses from the councils, we found:

- 27 councils have not reviewed the registration status of their engineering staff within the last 12 months

- 14 councils have a head of engineering who does not hold a current registration with the Board of Professional Engineers. Of these, 4 councils have a population over 10,000 residents, meaning these councils have substantial community assets.

Verifying whether their staff who perform professional engineering services are practicing engineers is a sound risk management practice for councils.

|

Recommendation for councils Annually review the registration status of employees undertaking engineering services |

|

3. Review the registration status of employees undertaking engineering services to make sure they are complying with the Professional Engineers Act 2002. Councils should do this on an annual basis. |

5. Financial performance

In this chapter, we analyse the financial performance of councils, with emphasis on their financial sustainability. The latter is measured under the Financial Management (Sustainability) Guideline 2012, issued by the Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works (the department).

Chapter snapshot

New sustainability measures are being introduced

The department has introduced a new guideline – Financial Management (Sustainability) Guideline (2023) – that applies to the sector from the 2023–24 financial year.

The new guideline considers the challenges that councils face, especially in rural and remote areas, and introduces more measures for the financial sustainability of councils. The department has grouped councils into tiers based on their remoteness and population, and each of the 8 tiers has different benchmarks for each measure.

This segmentation by tiers is a significant improvement to the previous financial sustainability guideline (Financial Management Sustainability Guideline (2013)) that had all councils trying to achieve the same benchmarks.

In Appendix L, we have listed the councils in each tier, and each tier’s benchmarks for the measures under the new framework. Figure 5B shows the 9 measures that councils will need to report on from 2023–24.

| Ratio | What it measures |

|

Operating surplus ratio1,2 |

The extent to which a council’s operating revenues (revenue earned from day-to-day business) cover its operational expenses (expenses incurred for day-to-day business). |

|

Operating cash ratio2 |

A council's ability to cover its operational expenses and increase its cash from its core operations – excluding depreciation expense (cost of allocating the value of an asset over its life). |

|

Unrestricted cash expense ratio3 |

How much money a council has available for its regular expenses and unexpected financial needs. |

|

Asset sustainability ratio2 |

How timely a council is in replacing its old assets as they wear out. |

|

Asset consumption ratio2 |

How much of a council's infrastructure assets have been used compared to what it would cost to build new assets with the same benefit to the community. |

|

Leverage ratio3 |

How easily a council can repay its debts. |

|

Council-controlled revenue4 |

How much of a council’s revenue comes from sources it can influence – such as being able to increase rates – to make sure it can deal with unexpected financial requirements. |

|

Population growth4 |

A key driver of a council’s operating income, service needs, and infrastructure requirements in the future. |

|

Asset renewal funding ratio4 |

The ability of a council to pay for its future asset renewal and replacement needs. |

1 Under the department’s guidelines, for tiers 6 to 8, the operating surplus ratio is contextual only – meaning that although these councils need to report this ratio, they do not have a benchmark for this ratio to measure their performance against.

2 Councils are required to report this ratio on a rolling 5-year average and for the relevant individual financial year.

3 Councils are required to report these ratios only for the financial year they are preparing the financial statements for.

4 The department has not assigned benchmarks for these measures, and they will not be audited.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office, using the Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works’s Financial Management (Sustainability) Guideline (2023).

The department’s framework for measuring financial sustainability risk can be improved

The department has also published a risk framework, which also applies from 1 July 2023.

The risk framework states that the department will gain insights into the financial sustainability of councils using the financial measures (in Figure 5B) and other, qualitative (non-financial) indicators (asset management, governance, compliance, and the broader operating environment).

However, the qualitative indicators are not prescribed in the risk framework or the sustainability guideline, nor are there clear benchmarks against which these qualitative indicators can be measured. The department has published these other qualitative indicators as a part of the ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ on its website.

If the expectations and criteria of these qualitative indicators are not clearly defined, councils will not understand what is required of them, and they will not be able to self-measure their performance and target areas for improvement.

|

Recommendation for the department Determine the minimum expected requirements for all qualitative measures of council sustainability and include this in the sustainability framework |

|

6. Amend the sustainability framework for Queensland councils to:

This will give councils a clear understanding of the qualitative elements they are being assessed against, and will help councils prioritise actions to improve them. |

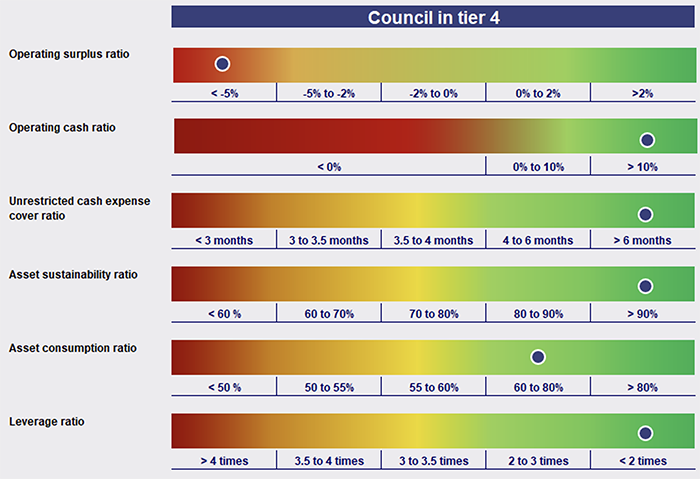

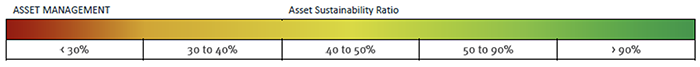

For each of the 6 audited ratios in the new framework, the department’s risk framework includes a table for each tier and ratio. These are based on a colour range from red to green, as shown in Figure 5C.

Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works, Risk Framework – Financial Sustainability.

This presentation shows a council where it sits on the ‘colour scale’ for each ratio. It gives no insight into the council’s risk of being financially unsustainable. This is because ratios are not assessed in totality and no measure of risk is assigned.

Ratios are not assessed in totality

The department’s risk framework refers to interpreting ratios in totality and provides some examples. However, each of these examples only discusses how 2 ratios would interact – not how to measure all ratios in totality. One example provided is of a council with a negative operating surplus ratio (incurring operating deficits – when council’s expenses exceed their revenue) but a positive operating cash ratio, and this being less of a concern for smaller councils.

Although incurring operating deficits in the short term is acceptable, when a council consistently incurs operating deficits, it will experience financial stress.

In such instances, a council will have no other option than to use its cash reserves to support its operations or reduce the level of services it provides to the community. Alternatively, it will have to rely on more funding from the state government to support its operations.

If ratios are presented individually in a ‘colour scale’ graph with no ability to interpret the overall result, they may result in different assessments depending upon the financial aspect being considered. This could in turn mean the department and the council focuses their efforts in areas of lesser importance.

No measure of risk is assigned

The risk framework states that it seeks to establish a sustainability reporting framework which encourages council leaders to understand the drivers of long-term sustainability. However, the framework does not assign a measure of risk to a council.

If a risk is not quantified, a council or the department will not be able to determine how critical the risk is and what action plans are required to mitigate this risk.

The case study in Figure 5D shows how difficult it is to interpret a council’s financial sustainability using the department’s risk framework. For this case study, we have used the 2022–23 results of a council in tier 4 to calculate the relevant ratios under the department’s risk framework.

Because the department’s risk framework does not provide an overall view of an individual council’s sustainability, it can only evaluate individual measures for each council.

In Appendix L, we have:

- categorised councils by tier (as per the department’s sustainability framework)

- shown for each tier, where councils would fall on the department’s risk assessment table for each of the measures that will be audited.

This presentation in Appendix L replicates how these ratios will be disclosed on the department’s risk framework. We have not derived our own risk assessment for these new ratios.

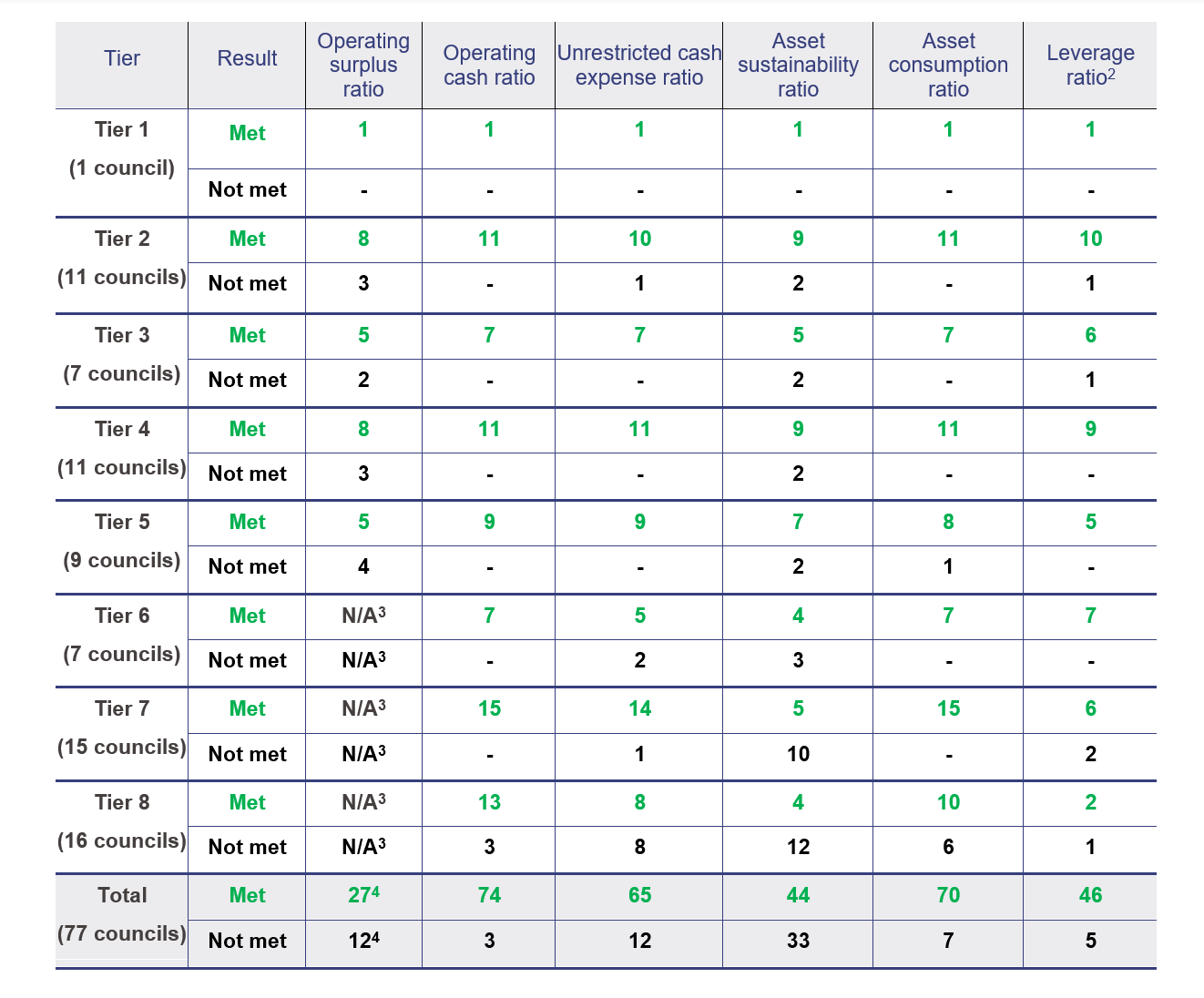

In Figure 5E, we summarise how many councils would have met the benchmark for each ratio, if the new ratios and risk framework were applied to councils’ 2022–23 financial results. While the figure does provide an overview of the sector’s performance, similar to the case study in Figure 5D, it is difficult to interpret how financially sustainable the sector is under the department’s current framework.

This is because it provides a lot of separate measures but does not prioritise whether certain ratios are more important than others, nor does it combine the ratios into a single overall measure of sustainability for each council. It is hard to get a picture of whether, in each tier, the councils that did not meet each ratio are the same councils or different councils.

Notes:

1 Only includes the 6 ratios that have a measurable benchmark.

2 Only applicable for councils that have borrowings.

3 Councils in tiers 6 to 8 do not have a benchmark for measuring their operating surplus ratios.

4 Total number of councils for operating surplus ratio is less than 77 as there is no benchmark for this ratio for tiers 6, 7, or 8.

In 2022–23, we have included the financial information of 14 councils using their last available certified financial statements as they had not completed 2022–23 by the 31 October statutory deadline.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office, from councils’ certified financial statements available 31 October 2023 – refer to Appendix C for further information.

|

Recommendation for the department Develop a way to measure the overall sustainability risk of individual councils |

|

7. Develop a way to measure the overall sustainability risk of individual councils. The methodology should also consider the impact on the overall financial sustainability if any of the benchmarks (identified for each ratio in the sustainability framework) are not met. This will help the department prioritise its resources for councils or groups of councils that need attention more urgently than others. It will also help councils understand what good looks like and how the department intends to use the ratios in total to assess the financial sustainability of councils. |

Sector’s operating results have improved, but only due to additional grant funding received in advance

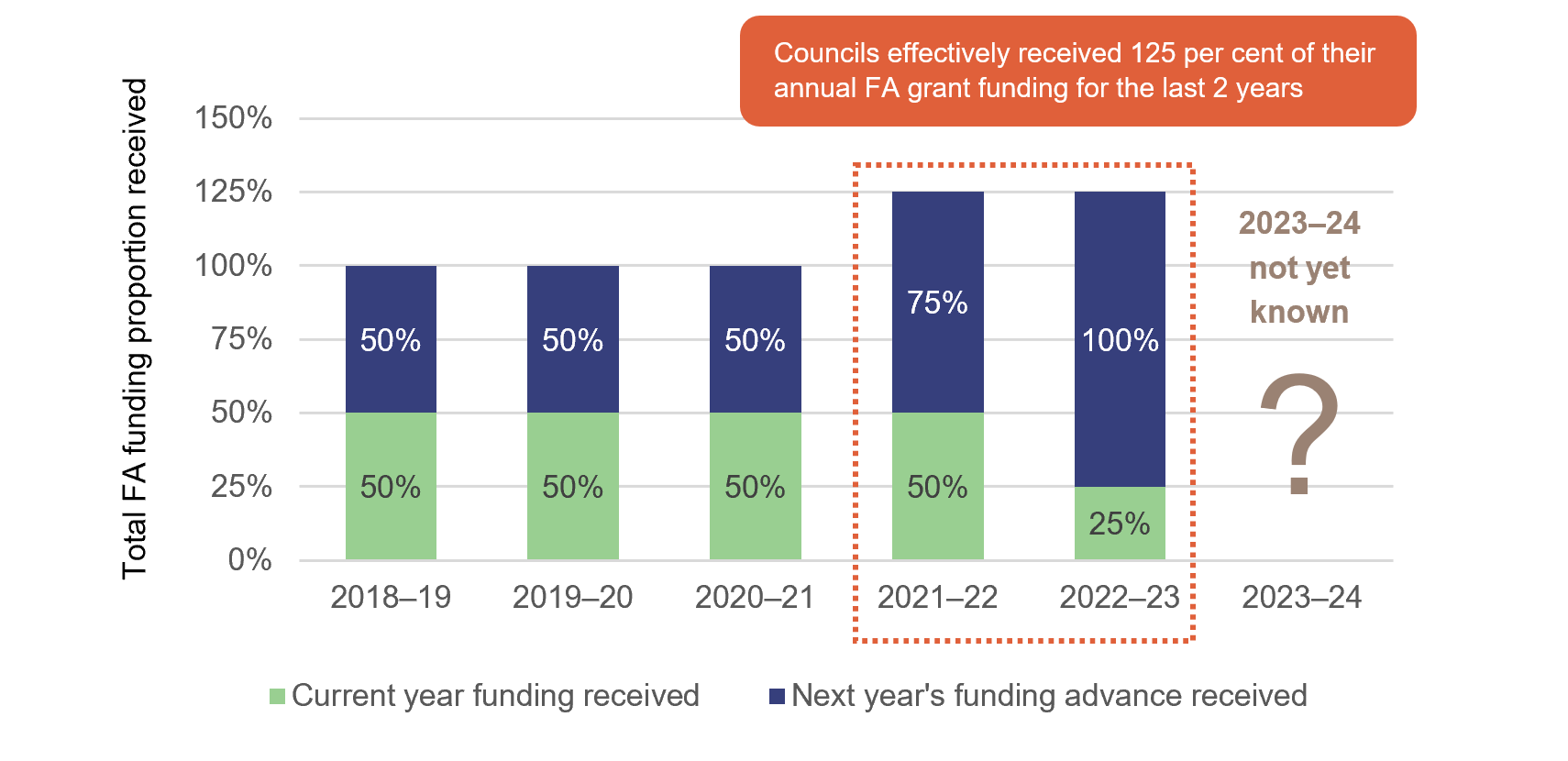

In June each year, councils usually receive roughly half of the next year’s federal government financial assistance grants (FA grants) in advance. These represent about 52 per cent of the total grants received by the sector. There is no certainty over how much advance funding will be made available each year, as it is entirely at the discretion of the Australian Government.

For the last 2 years, the Australian Government has increased the proportion of advance funding it has paid to councils in June, as shown in Figure 5F.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Due to the nature of these grants, they are reported as revenue when the cash is received by councils, meaning councils reported higher revenue in 2021–22 and 2022–23.

It is particularly concerning that, despite the sector receiving 100 per cent of its FA grants in advance, 20 per cent (15 councils) of the 63 councils that had completed their financial statements by 31 October 2023 incurred operating deficits.

While we are unable to conclude on the performance of the 14 councils that had not completed their financial statements as at 31 October 2023, all have incurred operating deficits in at least 3 of the last 5 financial years.

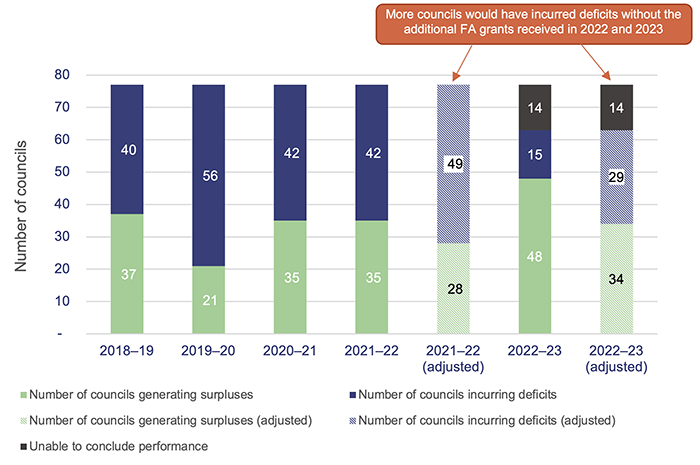

In Figure 5G, we show the sectors’ operating performance for the last 5 years, including what the results would have been if councils had not received larger advance funding for FA grants in 2021–22 and 2022–23. It highlights that if the increased levels of advance funding not been provided in the last 2 years, 49 councils last year, and 29 based on completed audits this year, would have made operating losses.

It is not uncommon for entities to incur operating deficits, especially in an environment when costs are rising significantly. This year, employee costs and materials and services costs increased by 6 per cent (2022: 5 per cent increase) and 9 per cent (2022: 10 per cent increase) respectively.

However, when entities incur operating deficits consistently, it may be due to poor budget monitoring or a combination of overspending and undercharging their community for services provided.

In Managing local government rates and charges (Report 17: 2017–18), we recommended councils implement an appropriate costing model to understand the full cost of delivering utilities, and that they use this information to annually review pricing for their rates. We also published our service prioritisation tool, which is available on our website at: www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/better-practice.

If councils do not set their rates and other charges at an appropriate level, they risk eroding their current cash reserves over time. If this occurs, they will find themselves under financial stress and may need to reduce the levels of service or completely stop providing some services to their communities.

The severity of the impact of such financial pressures will be felt more in the rural and remote areas, where councils provide ancillary services such as health care and child care, which are provided by private organisations in more populous areas.

The Australian Government’s decision to provide 100 per cent of the 2023–24 FA grant to councils in advance was not made until very late in June 2023. More councils may make losses in 2023–24 if the Australian Government advances less than 100 per cent of their 2024–25 FA grant funding in June 2024. Councils must get better at managing their budgets so they can deal with this uncertainty.

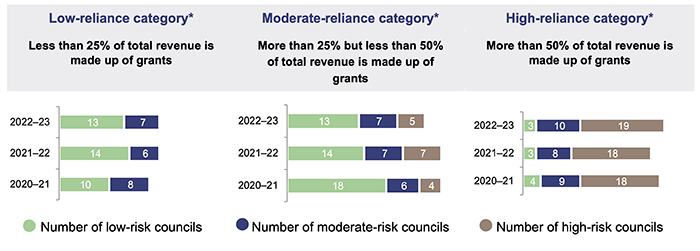

Reliance on grants affects the sector’s financial sustainability

Councils receive grant funding for their operational needs (conducting day-to-day business) and capital purposes (building and maintaining community assets). Without these grants, most councils would not be able to provide basic services to their communities or maintain their assets.

When a council increases its reliance on grants, its ability to be financially sustainable decreases. In Figure 5H, we have shown the financial sustainability of councils based on their reliance on grants (including both operating and capital grants). Our assessment is based on the audited ratios that applied to councils for 2022–23 and our own relative risk assessment as described in Appendix K.

Note: For 2022–23, we have included the financial information of 14 councils using their last available certified financial statements, as they had not completed 2022–23 by the 31 October statutory deadline. * Grant reliance is calculated using a 5-year average of grant funding as a percentage of total revenue.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from councils’ certified financial statements available 31 October 2023 (refer to Appendix C for more information).

Dependency on grants is unavoidable for the sector. This is because some councils, due to their remoteness and low population, cannot generate enough income to cover their costs. In Local government 2020 (Report 17: 2020–21) we recommended the department provide greater certainty over long-term funding. Since then, the department has released more multi-year grant programs such as the Works for Queensland Program and the South East Queensland Community Stimulus Program. Both are 3-year programs.

However, it is also important that councils make sure they have good budgeting and monitoring processes in place to be as financially sustainable as possible.

Councils that are heavily reliant on grants and yet remain financially sustainable have:

- prioritised financial governance by recruiting and retaining appropriately skilled staff

- established good financial and budgeting processes

- strong leadership and governance

- a strong internal control environment and oversight function, including effective audit committees and internal audit functions.

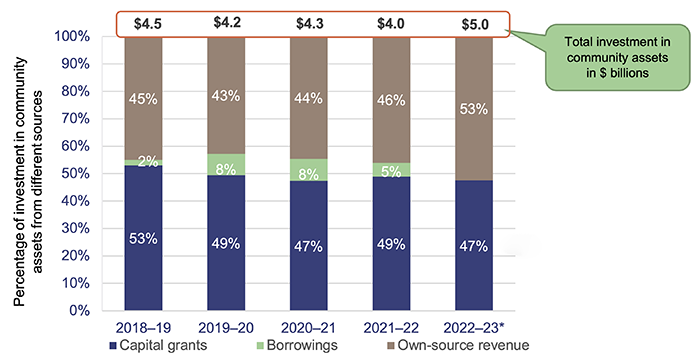

Investment in community assets is at its highest level in 5 years

Each year, councils invest significant amounts to maintain existing and build new assets for their community. This year, the sector invested $5 billion (2021–22: $4 billion). This is the highest expenditure the sector has seen in the last 5 financial years and has been funded from either grants or their operations, without the need to borrow.

Figure 5I shows the total investment in community assets together with how these were funded (capital grants, borrowings, and own-source revenue).

Note: In 2022–23, we have included the financial information of 14 councils using their last available certified financial statements, as they had not completed 2022–23 by the 31 October statutory deadline.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from councils’ certified financial statements available 31 October 2023 (refer to Appendix C for more information).

The larger spend this year is mostly due to the increased cost of procuring materials and labour. It is not because council assets are being maintained to the level that meets their communities’ needs.

This is explained below through our analysis of the asset consumption ratio – which measures the current value of a council’s assets relative to what it would cost to build new assets with the same benefit to the community.

The new sustainability framework recommends that for assets to meet community needs, the asset consumption ratio should be greater than 60 per cent. In Figure 5J, we show:

- councils whose assets are at a risk of not meeting community expectation – meaning those that do not currently meet the 60 per cent benchmark

- councils whose assets are at risk in the short term of not meeting community expectation – meaning those councils that have an asset consumption ratio of 61 per cent to 65 per cent

- councils whose assets are not at risk in the short term of not meeting community expectation – meaning those that have an asset consumption ratio greater than 65 per cent.

Note: In 2022–23, we have included the financial information of 14 councils using their last available certified financial statements as they had not completed 2022–23 by their 31 October statutory deadline.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

In Local government 2021 (Report 15: 2021–22), we recommended councils review their asset consumption ratio in preparation for the new sustainability framework. To date, 28 councils have either not yet done so, or where their asset consumption ratio is under 60 per cent, have not taken actions to improve it.

We continue to recommend that councils monitor their asset consumption ratio and ensure their assets are maintained at an appropriate level to meet the future needs of their communities.