Overview

Queensland’s local governments, also known as councils, play an important role in supporting the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of communities. They provide Queenslanders with various services, such as roads, water and waste, libraries, and parks.

Tabled 17 April 2025.

Report on a page

This report summarises the audit results of Queensland’s 77 local government entities (councils) and the entities they control. We also highlight the purpose and importance of accounting for depreciation expense.

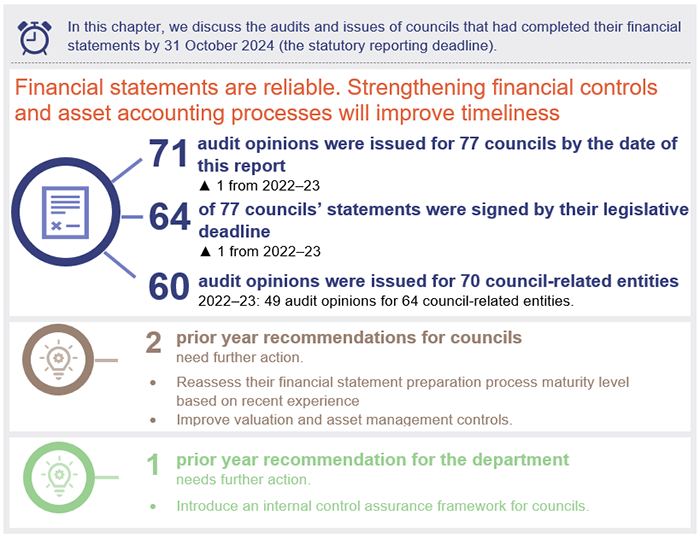

Financial statements are reliable, but not timely

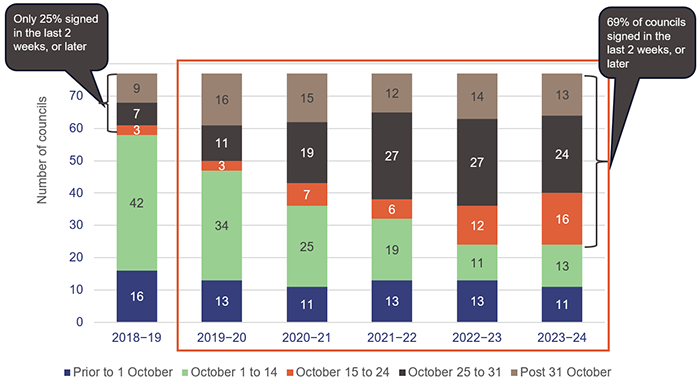

This year, 64 councils (2023: 63) had their financial statements completed by the statutory deadline of 31 October 2024. While the deadline was achieved by most councils, they are finalising their statements later. Over the last 2 financial years, more than two-thirds of the sector completed their financial statements in the last 2 weeks of October, or missed the 31 October statutory deadline. While a lack of adequate resources has played a part in this, weaknesses in councils’ processes have also contributed.

Allowing sufficient time for the financial statement preparation process will give councils opportunity to undertake a thorough review of the financial statements to identify and amend errors.

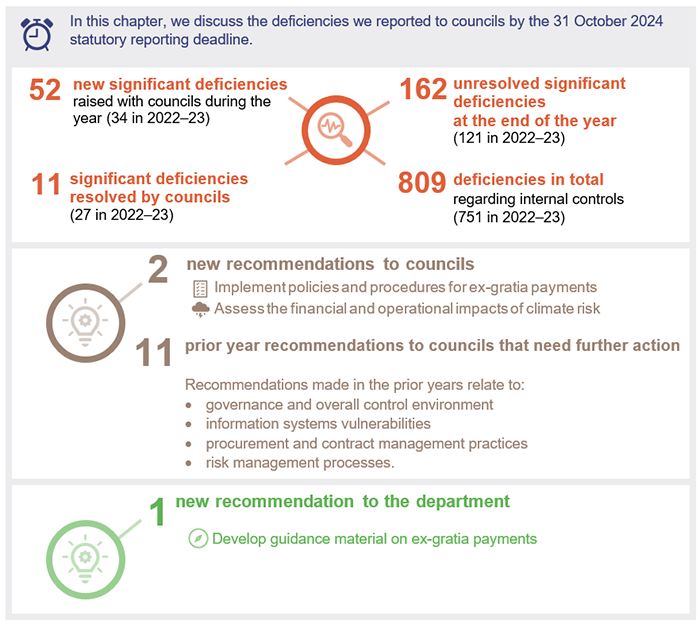

The sector’s control environment is weaker than before

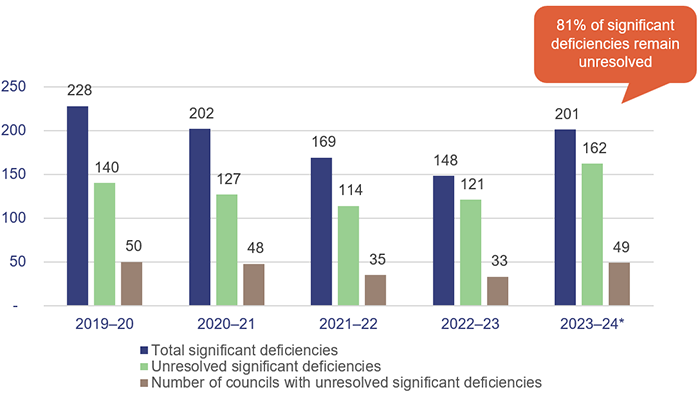

The sector’s control environment (its systems and processes) has deteriorated this financial year, with more than 200 new or unresolved significant deficiencies – of these 52 were identified and reported this year. Almost 80 per cent of the significant deficiencies have been unresolved for more than 12 months.

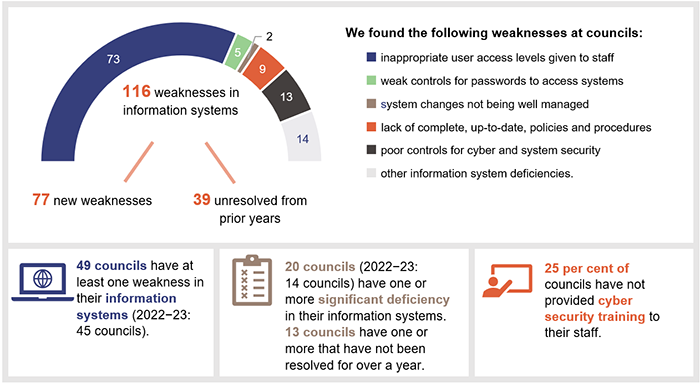

We continue to find more weaknesses in information systems, and 49 councils (2023: 45 councils) have at least one weakness. Councils need to address these in a timely manner to strengthen the security of their information systems. Weaknesses regarding procurement and contract management, and maintenance of policies and procedures have increased in the 2023–24 financial year.

Councils will need to consider the financial and operational impacts of climate-related risks and implement appropriate mitigation strategies.

There were many new elected members and executives due to the 2024 local government elections. These changes often result in changes to the governance structure and control environment in councils. They also meant that 10 councils combined paid $1.4 million in termination benefits to their existing executives above what they were entitled to under their contractual terms.

Federal grants were not paid in advance, leading to losses

Unlike previous years, in 2023–24 councils did not receive any advance funding through federal financial assistance grants. The federal government determines the timing of these payments. As a result, 52 councils (81 per cent of those that completed their financial statements by 31 October 2024) recorded losses.

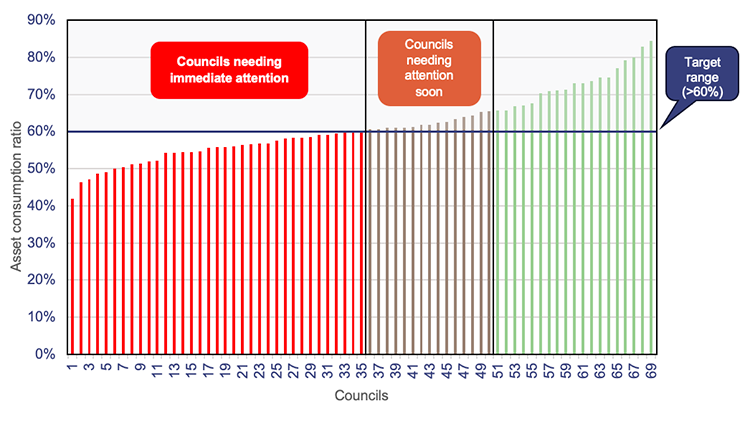

The sector’s water infrastructure assets need attention

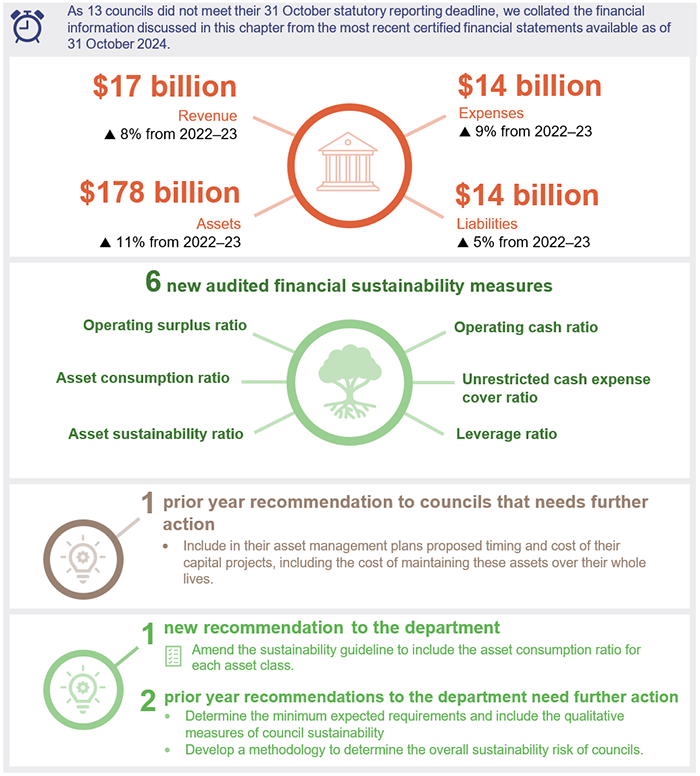

One of the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers’ (the department) new sustainability measures is the asset consumption ratio (how much of a council’s asset is left to be consumed). This ratio is currently calculated for all of councils’ infrastructure assets. If this ratio is measured at an asset type (roads, water infrastructure, for example) level, it would provide better insights to councils on what assets need attention.

When this ratio is applied to the sector’s water infrastructure assets, the ratio indicates that roughly half (35) of the councils are at an increased risk of not being able to provide services to their community at the required levels.

1. Recommendations

Recommendations for councils

This year, we make the following 3 new recommendations for councils.

Implement policies and procedures to ensure ex-gratia payments are appropriate and defensible, and the decisions made to make such payments are transparent. Consider the appropriateness of using non-disclosure agreements when making such payments (Chapter 5) |

1. We recommend that all councils implement policies and procedures that specify when ex-gratia payments (which an entity is not legally required to make under a contract or otherwise) are appropriate. The policies and procedures should outline:

|

| Assess climate risks and add them to their risk registers (Chapter 5) |

2. We recommend that councils assess climate risks and develop strategies to address them. They should consider updating their strategic plans, risk registers, and long-term budgets to reflect the financial and operating impacts of these risks. |

| Review the asset consumption ratio for water infrastructure assets and determine what action is required (Chapter 6) |

| 3. We recommend all councils review the asset consumption ratio for their water infrastructure assets. Where the ratio is below 60 per cent, councils should assess the need for repairs/renewals to their water infrastructure assets that will reinstate these assets to a level that provides the appropriate level of service to their community. |

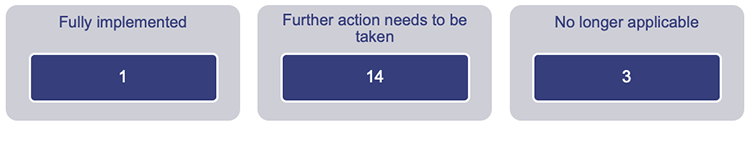

Councils need to take further action on prior year recommendations

We have summarised the recommendations that were outstanding in Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023–24) in the following tables.

Theme | Summary of recommendation | Local government report | Status of recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and internal control | Implement processes to ensure policies and procedures are regularly reviewed and kept up to date (Chapter 5) | Report 8: 2023–24 | Further action needs to be taken |

| Annually review the registration status of employees undertaking engineering services (Chapter 5) | Report 8: 2023–24 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Assess their audit committees against the actions in our 2020–21 audit committee report (Chapter 5) | Report 15: 2021–22 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Use our annual internal control assessment tool to help improve their overall control environment (Chapter 5) | Report 15: 2021–22 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Improve risk management processes (Chapter 5) | Report 17: 2020–21 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Establish and maintain an effective and efficient internal audit function (Chapter 5) | Report 13: 2019–20 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Asset management and valuations | Include councils’ planned spending on capital projects in asset management plans (Chapter 6) | Report 15: 2021–22 | Further action needs to be taken |

| Improve valuation and asset management practices (Chapter 4) | Report 17: 2020–21 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Financial reporting | Reassess the maturity levels of financial statement preparation processes in line with recent experience to identify improvement opportunities that will help facilitate early certification of financial statements (Chapter 4) | Report 15: 2021–22 | Further action needs to be taken |

| Information systems | Strengthen the security of information systems (Chapter 5) | Report 17: 2020–21 | Further action needs to be taken |

| Conduct mandatory cyber security awareness training (Chapter 5) | Report 13: 2019–20 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Procurement and contract management | Assess the maturity of their procurement and contract management processes using our procure-to-pay maturity model, and implement identified opportunities to strengthen their practices (Chapter 5) | Report 15: 2022–23 | Further action needs to be taken |

| Enhance procurement and contract management practices (Chapter 5) | Report 17: 2020–21 | Further action needs to be taken | |

| Secure employee and supplier information (Chapter 5) | Report 13: 2019–20 | Further action needs to be taken |

Implementing our recommendations will help councils strengthen their internal controls for financial reporting and improve their financial sustainability. We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix D.

Recommendations for the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers

This year, we make the following 2 new recommendations to the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department).

| Develop guidance material on ex-gratia payments for local governments (Chapter 5) |

4. We recommend that the department develops guidance material for councils to determine when ex-gratia payments are made. The guidance should:

|

| Amend the sustainability guideline to include an asset consumption ratio for each asset class (Chapter 6) |

| 5. We recommend that the department amends the sustainability guideline so that councils are required to calculate and report on the asset consumption of each asset class in their financial statements. |

The department needs to take further action on prior year recommendations

The department has made some progress in addressing the recommendations we made in our prior reports.

It has published a framework to assess the sustainability risk of councils. However, further action is still required on 3 recommendations, as summarised below.

Theme | Summary of recommendation | Local government report | Status of recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial reporting and capability within the sector | Introduce an internal controls assurance framework for councils (Chapter 4) | Report 8: 2023–24 | Not implemented |

| Financial sustainability | Determine the minimum expected requirements for all qualitative measures of council sustainability and include this in the sustainability framework (Chapter 6) | Report 8: 2023–24 | Not implemented |

| Develop a way to measure the overall sustainability risk of individual councils (Chapter 6) | Report 8: 2023–24 | Not implemented |

We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix D.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

2. Entities in this report

Queensland Audit Office.

3. Area of focus – accounting for depreciation expense

Queensland councils collectively manage $142 billion of infrastructure assets (roads, bridges, water assets) that are used to provide services to their communities. These assets usually have a limited life and are replaced throughout or at the end of their life. The replacement may be funded by council (using its own funds or through borrowings) or by another level of government, typically by provision of grants.

The allocation of the cost of the asset over its estimated life gives information on the value of the asset consumed by the community during a period of time – this is known as depreciation expense. This is valuable information, regardless of how the asset was funded. It provides information to allow for appropriate asset management, replacement planning, and costing of services.

Australian accounting standards require the calculation and reporting of depreciation expense in the annual financial statements. Depreciation expense is also included in some sustainability metrics.

In this chapter, we explain the fundamentals of depreciation and how councils can manage their depreciation expense and its financial impact.

Background

The financial reporting framework for councils in Queensland is determined by the Local Government Regulation 2012 (the regulation). It states that local governments in Queensland must prepare financial statements that comply with the Australian accounting standards. These standards are set by the Australian Government’s independent Australian Accounting Standards Board. All local governments around Australia need to comply with them.

Accounting for depreciation expense is a requirement of the Australian accounting standards.

Fundamentals of depreciation

What is depreciation

Depreciation is allocating the cost of the assets over the time they are expected to be consumed. Accounting standards allow for a variety of methods to calculate depreciation as long as it represents the systematic allocation of the consumption of the asset. Once selected, the method is applied consistently.

The simplest way to calculate depreciation expenses is to divide the value of an asset by its useful life (how long it is estimated to last). The figure for depreciation expenses, as reported in a council’s financial statements, is the aggregate amount of this calculation across all assets each financial year. The financial statements also provide a total of the amount of the asset consumed so far, called accumulated depreciation.

All methods of calculation of depreciation use estimates. The useful life is one of the key estimates in the calculation.

Why accounting for depreciation is important

To support the calculation of the cost of services

Councils provide various services to their communities, most for which they charge a fee. To support long-term sustainability, the fee charged should include the value of assets consumed to deliver those services.

Even where the full costs are not recovered by councils through fees, the gap identified helps councils to plan for the identification of future, alternate funding sources.

To help understand when assets need to be replaced

Effective management of assets means knowing when major repairs or replacement is required. When an asset ages, the amounts of value that can be derived from the asset decreases. As the net asset position of an asset (value less depreciation) approaches zero, this tells councils and readers that this asset will need to be replaced or significant maintenance is required.

All councils under the regulation are required to have an asset management plan. These plans must cover a period of 10 years or more and include:

- strategies on how the council will ensure sustainable management of its assets

- the estimated capital expenditure for renewing, upgrading, and extending the assets.

When councils maintain their assets in accordance with the asset management plan, they ensure their assets are safe and reliable to provide services to their community and also know how much longer their assets will last. As depreciation represents the reduction in the value of an asset over time, it is an important element of overall asset management and helps councils manage their assets effectively.

In Local government 2021 (Report 15: 2021–22), we made a recommendation to councils to review their asset management plans to confirm that they include the proposed timing and costs of replacement and significant repair of their assets. This would help them identify their future funding needs and help them to plan for appropriate sources of funding. As of 30 June 2024, only two-thirds (44 councils) of the sector had implemented this recommendation.

Depreciation should be accounted for monthly

Councils should calculate and account for deprecation expenses each month in the financial reports they prepare for their elected members, executives, and members of their community.

Accounting for deprecation in the monthly financial reports will:

- help councils plan better for their asset management and asset valuation processes

- provide councillors and other decision makers with the true financial position and performance of council throughout the year

- show a more accurate picture of councils’ financial sustainability on a periodic basis.

Councils should prepare their monthly financial reports on the same basis as they prepare their annual financial statements, which apply Australian accounting standards. This means applying the accrual basis of accounting (meaning revenue and expenses are recognised as they are earned or incurred, regardless of when cash has been received or paid).

This will ensure the elected members receive consistent and comparable monthly financial reporting that will align with the results of councils, to enable good decision making.

In our report Local government 2022 (Report 15: 2022–23), we reviewed about one-third of councils and compared the financial results they reported in their monthly financial reports (most of which were not prepared on an accrual basis) to their financial results in the audited financial statements (that were prepared on an accrual basis). We noted that:

- 14 councils (61 per cent of those we reviewed) reported a significantly lower operating result in their year-end financial statements than the operating result reported in their monthly financial reports

- for 6 of these 14 councils, they reported an operating surplus (operating revenue higher than operating expenses) in their monthly financial reports at 30 June 2022. But they reported an operating deficit (operating expenses higher than operating revenue) in their audited year-end financial statements.

In most instances, the reason for the difference in the operating results was because these councils did not account for depreciation in their monthly financial reports but recognised it in the annual financial statements.

Effectively managing the impact of depreciation

Depreciation is a significant component of a council’s total expenditure in the profit and loss statement. There are 2 key estimates used in the depreciation expense calculation, which can materially affect the value reported:

- the fair value of the asset – the value at which an entity will be able to sell or exchange its assets with a buyer. The higher the fair value of the asset, the higher the depreciation expense

- the useful life of the asset – an estimate of how long an asset will last. The shorter the useful life of the asset, the higher the depreciation expense.

Most council assets are of a nature that cannot be easily sold to a buyer – for example roads, drainages, and bridges. Fair value of such assets is calculated by reference to what it would cost to replace these assets in their current form and condition. This is known as current replacement cost.

Councils often engage independent valuers to determine the current replacement costs and remaining useful lives of assets. To get these right, councils must work closely with the independent valuers to ensure that the asset values and useful lives are reflective of their experience of the costs of recent projects and of past asset replacement time frames.

In the following case study, we highlight an example of how a Queensland council has used its internal data and experience of its engineers and asset management teams to challenge the valuer’s judgements and estimates, resulting in a lower annual depreciation expense.

| Managing the value and useful lives of assets |

|---|

In the 2022–23 financial year, a large council in Queensland engaged the services of an independent valuer to determine the current replacement costs and the useful lives of its water and sewer assets. This valuer was also engaged for 2 previous financial years. Over a 3-year period, the value of this council’s water and sewer assets, as determined by the valuer, increased by approximately 60 per cent. In the same period, the useful lives of the assets declined. The engineers and asset management team at this council collaborated with the valuer to understand the reason for the increase in values. They compared the values to recent projects undertaken to corroborate their cost of the construction of similar assets. They noted that the increase of their cumulative costs during this 3-year period was around 40 per cent. The engineers and asset management team also used maintenance and repairs data to challenge the useful lives determined by the valuer. The team was able to demonstrate that the useful lives of its assets were higher than what the valuer had estimated. In the end, by critically assessing and challenging the independent valuer’s inputs, the council was able to reduce its asset value and increase the useful lives of its water and sewer assets. This resulted in a decrease of approximately $9 million or 7 per cent of its total depreciation expenses. |

Queensland Audit Office.

Opportunities for councils

|

4. Results of our audits

This chapter provides an overview of our audit opinions and the results of our audits of entities in the local government sector, timeliness of councils’ financial statement certification, and the common issues that prevent councils from achieving timely financial statement certification.

Chapter snapshot

Appendix D provides the full detail of all prior year recommendations made to councils and the department.

We express an unmodified opinion when financial statements are prepared in accordance with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards.

We issue a qualified opinion when financial statements as a whole comply with relevant accounting standards and legislative requirements, with the exceptions noted in the opinion.

We include an emphasis of matter to highlight an issue of which the auditor believes the users of the financial statements need to be aware. The inclusion of an emphasis of matter paragraph does not change the audit opinion.

Audit opinion results

Audits of financial statements of councils

As of the date of this report, we have issued audit opinions for 71 councils (2022–23: 70 councils). Of these:

- 64 councils (2022–23: 63 councils) met their legislative deadline

- 3 councils (2022–23: 4 councils) met the extended time frame granted by the Minister for Local Government – who may grant an extension to the legislative time frame where extraordinary circumstances exist

- 5 councils (2022–23: 6) that received ministerial extensions did not meet their extended time frame

- one council (2022–23: 3) that had its financial statements certified past its legislative deadline did not seek an extension from the minister.

The financial statements of councils and council-related entities are reliable

The financial statements of the councils and council-related entities for which we issued opinions were reliable and complied with relevant laws and standards.

We issued a qualified opinion for one council-related entity – Local Buy Trading Trust (controlled by the Local Government Association of Queensland Ltd). This was because we could not ensure that the revenue recorded in the financial statements was the total amount of revenue that it should have collected. We issued a qualified opinion for this entity last financial year for the same reason.

We included an emphasis of matter in the audit opinions for 4 council-related entities because:

- one was reliant on financial support from its parent entities

- 3 had decided to wind up their operations.

Not all council-related entities need to have their audits performed by the Auditor-General. Appendix F provides a full list of these entities.

Timely financial reporting will ensure that information provided to communities is current and relevant

In recent years there has been a decline in councils’ timely completion of financial statements, which means the information they provide to their communities and other stakeholders is not current. When the financial information is not current, it is not as relevant.

In the last 2 financial years (2022–23 and 2023–24), about 69 per cent of councils have completed their financial statements in the last 2 weeks before the deadline or missed the 31 October statutory reporting deadline. In 2018–19, only 25 per cent of councils completed their financial statements this late.

Figure 4A shows the reduction in timeliness of financial reporting across the sector. We have compared the last 5 financial years’ results to the results of the 2018–19 financial year.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Timely financial reporting can be achieved by planning better

Councils that prepare well in advance and ensure they have appropriate controls are more likely to achieve timely reporting. When they plan better and give themselves sufficient time, it will allow them to perform a thorough quality review of the financial statements and other information provided to the auditors. This will ensure that any errors in the financial statements are detected and amended in the correct financial year.

Each year, we agree with councils their key milestones for their financial statement processes. There are 2 key finalisation dates for the completion of the process. One is the approval and certification of the statements by the entity; the second is the issue of the audit opinion.

Councils can use the resources made available by the department (such as month-end reporting templates and a timetable to prepare for the year-end process) together with the key milestones agreed with the auditors, to assist in improving their financial reporting timeliness.

Opportunities for councils – better planning for financial statements improves quality and timeliness of financial statements Preparing for timely financial reporting includes:

|

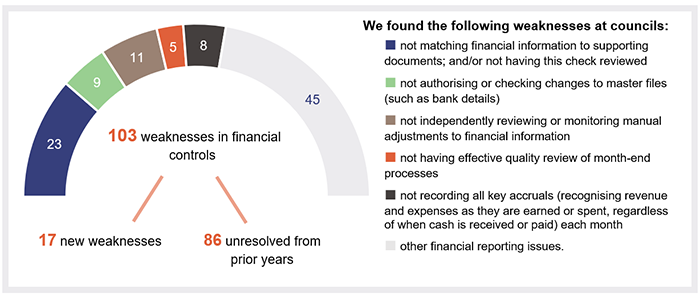

Councils to improve common financial reporting issues

Strong financial controls help to prevent and correct errors earlier and assist with timely and quality financial reporting.

Although we have seen some improvements over the last financial year, as of 30 June 2024, there were 101 unresolved weaknesses (2023: 144 unresolved weaknesses) related to councils’ financial controls. Of these weaknesses, 86 had been unresolved for more than 12 months.

Section snapshot 4.1

Focus on month-end processes

Strong month-end processes help assist with timely and quality financial reporting. These ensure the accuracy of council’s financial records, that balances are reconciled throughout the year, and that any discrepancies and errors are identified and resolved.

Good month-end processes also ensure accurate and complete financial information is provided to the elected members, who are responsible for making financial decisions on behalf of council. Some examples of good month-end processes are provided below.

Examples of good month-end processes:

|

Controls to protect against fraud

All entities should exercise due care when changes are made to supplier and employee information, also known as masterfile data. Masterfile data includes bank account details, which are susceptible to fraud. Appropriate controls help entities confirm the legitimacy of requests to change details and manage fraud risk.

Most councils have implemented protective controls; however, this year, one council became the victim of a fraud that resulted in a substantial financial loss. Several other councils were targeted, but in those instances the fraud attempts were not successful due to their strong internal controls.

In Figure 4B, we provide details of the fraud that was perpetrated against this council, which highlights the significant impacts that can arise where internal controls do not operate in the way they were designed.

Supplier masterfile fraud – case study |

|---|

In the 2023–24 financial year, one Queensland council fell victim to supplier-related fraud. This resulted in a financial loss of $2.8 million. In this instance, the fraudster was able to successfully change the contact details and the bank account details of a legitimate supplier. The fraudster was able to do this through a combination of written requests, as well as through phone conversations with accounts payable team members. Council engaged an external specialist to perform an independent investigation of the circumstances that resulted in the financial loss. The investigation identified several internal control breakdowns, including:

Following this investigation, the council has taken action to strengthen its processes and implement a series of new controls. These include enhancing its documentation to support changes to supplier details and developing a checklist to address the issues that led to the fraud. |

Queensland Audit Office.

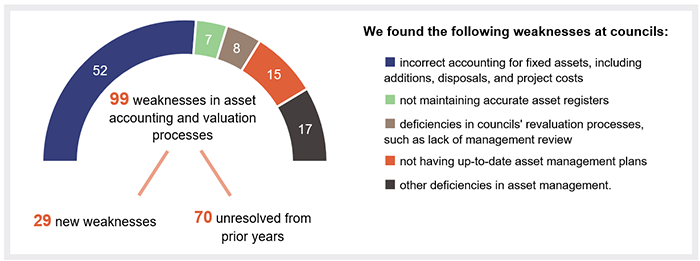

Asset accounting and valuation processes need to improve

As of 30 June 2024, the sector managed $142 billion of infrastructure assets. Accounting for and valuing assets is a key risk area and needs a continued focus on improvement.

Section snapshot 4.2

Common issues we continue to see with asset valuation processes include:

- delays in engaging with external valuers in determining fair values and useful lives

- not providing clear instructions to the valuer on what assets to value

- not undertaking a thorough review of information provided by external valuers, resulting in several errors

- not challenging the valuer’s estimates and judgements in line with council’s own experience in constructing similar assets.

Incorrect and inaccurate asset data has resulted in councils having to recognise found assets (assets that councils have owned but not previously reported in their financial statements) every year. Although, in some instances found assets have also been identified because of councils undertaking data cleansing exercises to improve their asset data.

In 2023–24, 12 councils combined identified $255 million ($190 million in 2022−23) of found assets and reported them for the first time in their financial statements. These councils had to restate their prior year financial statements to reflect the correct amount of assets that should have been recognised.

Some found assets have been donated to councils, either by another level of government or by property developers that undertake various developments in council areas. To recognise these donated assets, councils need to work collaboratively with their:

- town planning/development services team – which manages the developer’s progress on the project

- engineering team – which provides certification on the quality of assets donated by the developer before council can assume ownership of the assets

- finance team – which accounts for these donated assets in the financial statements.

The main reason for councils recognising found assets each year is due to:

- not having good quality asset data – it is either incomplete or outdated

- a lack of adequate collaboration between respective teams in the council (listed above)

- councils not undertaking periodic reconciliation of the assets recorded in the financial systems and the assets held in geographical information systems (which are used to capture, store, and manage detailed components of assets, including their geographical location).

From 2019−20 to 2023−24, the sector has identified approximately $1.2 billion in found assets |

In June 2023, we published a blog on Asset management – where do I start?, which is available on QAO’s website: www.qao.qld.gov.au/blog. This blog provides guidance on how public sector entities can ensure completeness of assets – which in turn leads to improved asset accounting.

We highly encourage councils to read this blog and implement any appropriate changes to their processes.

Opportunities for councils – improve asset accounting processes

|

Update on entities that missed the statutory deadline in the 2022–23 financial year

At the time we compiled Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023–24), 14 councils and 17 controlled entities had not completed their financial statements. Since then, the following councils and controlled entities have completed their financial statements as shown in Figure 4C and Figure 4D.

Council | Financial year | Date audit opinion issued | Type of opinion issued |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mornington Shire Council | 2021–22 | 16.05.2024 | Unqualified |

| Northern Peninsula Area Regional Council | 2021–22 | 20.05.2024 | Unqualified |

| Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council | 2021–22 | 15.05.2024 | Qualified1 |

| Barcaldine Regional Council | 2022–23 | 16.02.2024 | Unqualified |

| Blackall-Tambo Regional Council | 2022–23 | 12.12.2023 | Unqualified |

| Burke Shire Council | 2022–23 | 30.11.2023 | Unqualified |

| Cloncurry Shire Council | 2022–23 | 24.05.2024 | Unqualified |

| Cook Shire Council | 2022–23 | 15.12.2023 | Unqualified |

| Diamantina Shire Council | 2022–23 | 31.01.2024 | Unqualified |

| Etheridge Shire Council | 2022–23 | 15.11.2023 | Unqualified |

| Gympie Regional Council | 2022–23 | 30.11.2023 | Unqualified |

| Lockhart River Aboriginal Shire Council | 2022–23 | 14.11.2023 | Unqualified |

| Mornington Shire Council | 2022–23 | 20.12.2024 | Unqualified |

| Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council | 2022–23 | 12.12.2023 | Unqualified |

Note: 1 Council was unable to provide sufficient evidence of the completeness for its lease and motel revenue, service charges and landing fees, accommodation income, and employee expenses.

Queensland Audit Office.

Entity | Financial year | Date audit opinion issued | Type of opinion issued1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Queensland Local Government Association | 2021–22 | 23.05.2024 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

| Ipswich Arts Foundation | 2022–23 | 05.03.2024 | Unqualified |

| Mackay Region Enterprises | 2022–23 | 09.11.2023 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

| Mount Isa City Council Owned Enterprises Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 21.02.2024 | Unqualified |

| NQ Spark Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 24.09.2024 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

| TradeCoast Land Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 07.02.2024 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

| Council of Mayors SEQ Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 08.03.2024 | Unqualified |

| Major Brisbane Festivals Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 31.05.2024 | Unqualified |

| SEQ Regional Recreational Facilities Pty Ltd | 2022–23 | 18.03.2024 | Unqualified |

| Townsville Breakwater Entertainment Centre Joint Venture | 2022–23 | 24.01.2024 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

| Western Queensland Local Government Association | 2022–23 | 28.05.2024 | Unqualified with an emphasis of matter |

Note: 1 Refer to Appendix E for further details on the various emphasis of matters.

Queensland Audit Office.

5. Internal controls at councils

In our audits, we assess whether the systems, people, and processes (internal controls) used by entities to prepare financial statements are reliable. In this chapter, we report on the effectiveness of councils’ internal controls and provide areas of focus for them to improve on.

When we identify weaknesses in the controls, we categorise them as either deficiencies (those of lower risk that can be corrected over time) or significant deficiencies (those of higher risk that require immediate action by management). We report any weaknesses in the design or operation of those internal controls to management for their action.

Chapter snapshot

Appendix D provides the full detail of all prior year recommendations made to councils and the department.

Guidance needed for ex-gratia payments made by councils

The local government elections held in March 2024 resulted in significant changes across Queensland councils.

Queensland Audit Office.

Elected officials (mayors and councillors) and chief executive officers are responsible for setting the strategic direction, tone, and culture of an organisation and influencing its governance practices.

There is often a significant change to chief executive officers (CEOs) and other executives after local elections, as highlighted above from the 2024 elections.

During periods of leadership change, councils need extra safeguards and controls. An audit committee and internal audit function can support governance and oversight.

30 councils have a new CEO following the 2024 local government elections |

Termination payments were made to some executives over and above their entitlements

Chief executive officers and other executive leaders are usually employed under contracts that identify what they are entitled to upon termination of their employment.

Termination payments typically include accrued leave, and any termination benefits such as long service leave payouts. In some instances, they also include severance payments for early termination of their contracts. For executives that are key management personnel – those who are involved in strategic decision making for councils – details of their remuneration and other benefits, including termination benefits, are separately disclosed in the council’s financial statements.

In 2023–24, councils collectively paid $6.4 million in termination payments to key management personnel. Included in these termination payments were amounts totalling to $1.4 million paid over and above what these executives were entitled to under their employment contracts. These amounts are referred to as ‘ex-gratia’ payments.

There were also ex-gratia payments made to employees that exited councils during the year. These employees were not considered key management personnel and, therefore, their payments are not separately disclosed in the financial statements. As such, the actual level of ex-gratia payments made across the sector was higher.

The financial reporting requirements mandated by Queensland Treasury for state public sector entities require ex-gratia payments to be disclosed in the financial statements. There are currently no such requirements for local governments in Queensland. This means there is limited transparency when councils make these payments.

Ex-gratia payments are often made using non-disclosure agreements. The nature of these agreements means the terms of the payment cannot be discussed or shared without permission. There may be legitimate reasons why these agreements are made, but they do decrease transparency and increase the risk of fraud and wrongdoing. Entities should consider whether they are required in each circumstance.

The Crime and Corruption Commission’s publication Use of non‑disclosure agreements – what are the corruption risks? raises concerns over the use of non-disclosure agreements, particularly in employee separation settlements. The commission raised concerns that they may be used to conceal suspected wrongdoing or make payments that are unjustified or excessive.

Entities lack clear guidance for ex-gratia payments

The common issue we identified is that there is no clear policy or guidance in place to outline:

- when these types of ex-gratia payments are appropriate

- the basis for determining the amount paid

- who can approve them.

Recommendation to all councils Implement policies and procedures to ensure ex-gratia payments are appropriate and defensible, and the decisions made to make such payments are transparent. Consider the appropriateness of using non-disclosure agreements when making such payments 1. We recommend that all councils implement policies and procedures that specify when ex-gratia payments (which an entity is not legally required to make under a contract or otherwise) are appropriate. The policies and procedures should outline:

|

Recommendation to the department Develop guidance material on ex-gratia payments for local governments 4. We recommend that the department develops guidance material for councils to determine when ex-gratia payments are made. The guidance should:

|

More control deficiencies were identified this year

This year, the sector had more than 200 significant deficiencies that were either new or unresolved from previous years. This is the highest number of unresolved significant deficiencies that the sector has had since the 2019–20 financial year.

As of 30 June 2024, 81 per cent of these significant deficiencies remain unresolved from prior years.

The number of councils with significant deficiencies has also increased in the 2023–24 financial year, with 49 councils (2023: 33 councils) having at least one unresolved significant deficiency.

Figure 5B shows the total significant deficiencies and unresolved significant deficiencies across the sector.

Note: * Number of significant deficiencies reported for 2023–24 includes significant deficiencies from 2020–21, 2021–22, and 2022–23 for councils that completed their financial statements since we tabled Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023–24) in January 2024.

Queensland Audit Office.

Significant deficiencies can result in financial and/or reputational losses and increase the risk of fraud in an organisation. As reported in the recent QAO blog, How understanding the ‘fraud risk triangle’ can reduce employee fraud risk (available at www.qao.qld.gov.au/blog), employee-committed frauds in organisations have been on the rise, especially in the last few years.

Audit committees and internal audit support strong control environments

We continue to find that most of the unresolved significant deficiencies that have been outstanding for more than a year are in councils that do not have strong governance. Governance relates to the structures, processes, and practices through which a council is managed, controlled, and held accountable. Audit committees and internal audit are elements of good governance.

Figure 5C below shows that councils that do not have an audit committee and/or an internal audit function have a higher proportion of unresolved significant deficiencies.

|

Audit committees |

Internal audit |

As of 30 June 2024:

1 Includes one council whose audit committee ceased during the year. | As of 30 June 2024: 11 councils (2023: 9 councils) did not have an effective internal audit function. This is made up of:

|

| Those councils with no audit committee function, or audit committees that did not meet, had a combination of 86 unresolved significant deficiencies (53 per cent of all unresolved significant deficiencies). | These councils combined had 55 unresolved significant deficiencies (34 per cent of all unresolved significant deficiencies). |

| 8 councils do not have either an audit committee or an internal audit function. These councils combined have 51 unresolved significant deficiencies as of 30 June 2024. | |

Queensland Audit Office.

What do audit committees do?

An effective audit committee plays a pivotal role in providing oversight to management to help fulfil responsibilities relating to financial reporting, internal control systems, risk management systems, and internal audit.

In Insights on audit committees in local government (Report 10: 2024–25), we explore the role of audit committees and the benefits they can provide to Queensland’s local governments.

What does internal audit do?

An active internal audit function is a mandatory requirement for all councils under the Local Government Regulation 2012. An effective internal audit function provides unbiased assessments of operations and continuous review of the effectiveness of governance, risk management, and control processes. Internal auditors evaluate risks and can assist in establishing effective fraud prevention measures by assessing the strengths and weaknesses of controls.

While the regulation does not specify what the internal audit function must cover, to properly evaluate councils’ risks, it should focus on more than just financial operations.

We plan to survey the sector for our next local government report to better understand what work is being performed by internal audit. This should identify potential gaps that councils can address to improve their internal capabilities and better manage risks.

Common internal control weaknesses

Each year, as a part of our audit, we assess the control environment of the sector. Weaknesses in the control environment are reported to the councils. In Figure 5D, we have shown the sector’s control weaknesses grouped by themes and the number of years they have remained unresolved.

Queensland Audit Office.

We discussed weaknesses in financial controls and asset management in Chapter 4. In this chapter, we cover the other common internal control weaknesses shown in Figure 5D above.

The sector’s information systems are vulnerable

Section snapshot 5.1

Source: Queensland Audit Office.

Councils rely on their information systems for their day-to-day operations. This year, we identified 77 new weaknesses (2023: 66) in these systems. Resolving these deficiencies in a timely manner will strengthen their information systems and make them less vulnerable to cyber attacks.

One of the most common reasons organisations are victims of cyber attacks is that their staff are not appropriately trained to identify and respond to potential threats. Eleven councils (2023: 17 councils) did not provide mandatory cyber security training to their staff this year and 9 councils have not updated their staff on the risk of cyber attacks for more than a year.

To help entities improve their controls over their information systems, we have tabled 2 reports: Managing cyber security risks (Report 3: 2019–20) and Responding to and recovering from cyber attacks (Report 12: 2023–24). Councils should consider the recommendations in these reports and implement those applicable to them.

Cyber risks are often increased when councils engage third-party service providers to manage their information systems. Our Forward work plan 2024–27 includes a future audit covering this area

Opportunities for councils – make use of appropriate resources The department, in collaboration with the Queensland Chief Customer and Digital Officer (QGCDO), has been educating councils on the services and assistance that the QGCDO can offer the local government sector. We strongly encourage councils to use this service and the assistance available to them. |

Procurement and contract management processes need to improve

Section snapshot 5.2

Source: Queensland Audit Office.

Over the last 5 years (2019−20 to 2023−24), councils have, on average, spent $9 billion each year for operational and capital (major projects) purposes. Almost 50 per cent of councils have at least one weakness in their procurement and contract management processes.

Obtaining value for money in the procurement process is important for councils, who are accountable to the community. Better value for money can be derived by implementing strong:

- procurement controls – prior to acquiring goods and services, such as obtaining multiple quotes to ensure the pricing you obtain is competitive

- contract management controls – after acquiring goods and services, like evaluating supplier performance to ensure that the supplier has delivered what it promised and within the time frames specified.

A contract register is a critical control that supports councils to budget for committed costs, track their obligations, and prepare for contracts ending ahead of time.

A well-maintained contract register can help manage contract variations by providing a centralised repository to track all changes made to existing contracts, including:

- details about the nature of the variation

- the reason for the change

- any cost or schedule impacts

- the updated terms.

This will allow easier monitoring and control of contract modifications across an organisation.

Five councils (2023: 5 councils) did not have a contract register or did not have a complete contract register at the time of our audit. These councils combined spent $936 million in the 2023−24 financial year in procuring various goods and services.

Content of a good contract register At a minimum, a contract register should include:

|

The Queensland Audit Office (QAO) maturity model

When we tabled Local government 2022 (Report 15: 2022−23), we published a maturity (procure-to-pay) model that councils can use to assess their procurement and contract management practices. It is available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/better-practice. It aims to help councils identify and implement improvement opportunities. In that report we recommended that councils undertake a self-assessment of their practices using this model.

As of 30 June 2024, only 29 councils had undertaken this self-assessment to determine their strengths and identify opportunities for improvement.

Opportunities for councils – strengthen procurement and contract management controls Councils should:

|

Councils need to ensure they have up-to-date policies and procedures

Section snapshot 5.3

Source: Queensland Audit Office.

Policies and procedures help shape a council's culture and ensure appropriate employee conduct and internal controls. Policies define rules, while procedures explain how to follow those rules.

As of 30 June 2024, we had identified 19 weaknesses (2023: 17) across the sector where councils do not have policies and procedures in place or have outdated policies and procedures that do not meet their business needs.

Having good policies and procedures will promote consistent practices. They also allow good decision making and prevent financial loss or non-compliance with legislation.

With the recent local government elections, there are now elected members and chief executive officers who may be new to local government, or to a particular council. Up-to-date policies and procedures will help on-board the elected members and chief executive officers and provide a framework that ensures compliance with legal and other obligations, including sound internal controls.

Councils have not acted on recommendations to improve risk management processes

Section snapshot 5.4

Source: Queensland Audit Office.

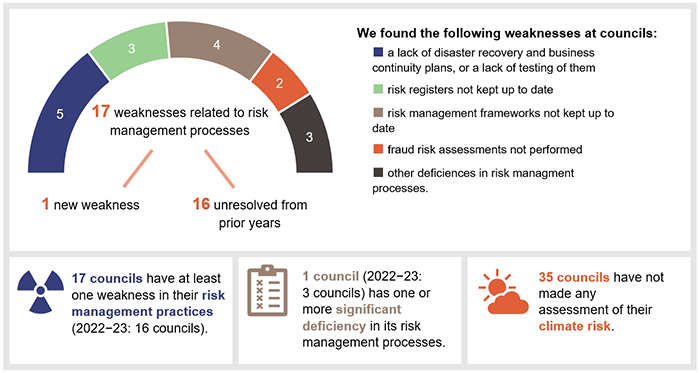

We only identified one new deficiency with risk management controls in the 2023–24 financial year, but there are several longstanding deficiencies councils have not addressed. Strong and robust risk management practices will assist councils in mitigating the risks they face and in achieving their strategic objectives.

Climate risk

Councils potentially face climate-related challenges such as heatwaves, droughts, bushfires, and rising sea levels that could damage their assets, disrupt essential community services, affect local industries, and pose health risks to their communities.

In 2022−23, we surveyed councils to understand how mature the sector’s knowledge of climate risk was. Only 38 councils (approximately 50 per cent) recognised the impact of climate as a key risk they needed to manage.

In September 2024, the Australian Accounting Standards Board issued 2 new sustainability standards on climate reporting. These standards are not mandatory for local governments in Queensland.

The department is expected to provide guidance to councils if these standards become applicable to the sector. In preparation, councils should consider climate risk as a part of their strategic and operational planning and put measures in place to mitigate this risk. This would assist councils in not only managing this risk well but also in being better prepared for disclosing information required in the financial statements.

Recommendation for all councils Assess climate risks and add them to their risk registers 2. We recommend that councils assess climate risks and develop strategies to address them. They should consider updating their strategic plans, risk registers, and long-term budgets to reflect the financial and operating impacts of these risks. |

Update on entities that missed the deadline for last year’s report

At the time we compiled Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023−24), 14 councils had not completed their financial statements.

Since then, 11 of these 14 councils have completed the financial statements, and our audit identified 9 new significant deficiencies and 25 new deficiencies in their internal control processes.

The 9 new significant deficiencies are as follows:

|

Financial controls |

Procurement |

Other issues |

| 3 significant deficiencies noted with respect to month-end processes, including not appropriately checking changes to supplier bank account details* and managing grants | 2 significant deficiencies noted with respect to councils not following procurement policy | 4 significant deficiencies noted with respect to compliance with laws and regulations and record keeping |

Note: * This topic is addressed in Chapter 4.

6. Financial performance

This chapter analyses the financial performance of councils, with emphasis on their financial sustainability. This is measured against the Financial Management (Sustainability) Guideline (2024), issued by the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department).

Chapter snapshot

Appendix D provides the full details of all prior year recommendations we have made to councils and the department.

Financial sustainability in local government

Financial sustainability in local government is a very topical issue across Australia. It has attracted so much attention in the last few years that the Australian Government is conducting a nationwide inquiry into local government sustainability (www.aph.gov.au/LocalGovernmentSustainability).

All local governments receive grants (known as financial assistance grants) for their day-to-day operations. These grants supplement the revenues of councils and form a substantial part of the sector’s funding.

The financial assistance grants (FA grants) are allocated to each council based on a determination by the Grants Commission – an independent body appointed by the Governor of Queensland, with funding received from the Australian Government.

Councils were originally set up to provide 4 essential services to their community: roads, water, waste collection, and wastewater. However, in regional Queensland (which makes up 70 per cent of the councils in terms of numbers), they also provide various other services such as airports, child care, and aged care centres.

These services are typically delivered by private sector providers in larger cities and towns where there is enough population to avail these services. In regional communities, due to their low population, these services are not attractive business propositions for private service providers. If councils did not provide the services, they may not be available to the community.

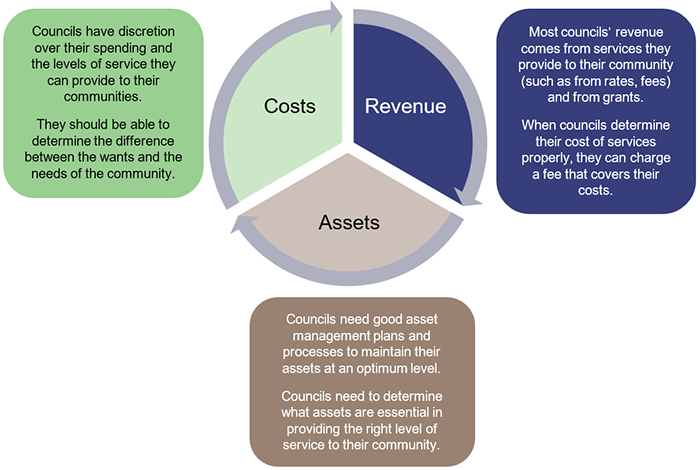

The cost of providing these services is often much higher than the fee that councils charge their community. As such, being financially sustainable has increasingly become a challenge for most councils in Queensland. Figure 6A explains the 3 key components of financial sustainability and councils’ ability to control them.

Queensland Audit Office.

Managing all of these components effectively is key to being financially sustainable. However, councils also need:

- good governance (such as an audit committee and an internal audit function – explained in Chapter 5)

- strong internal control frameworks in which significant deficiencies are resolved in a timely manner (also explained in Chapter 5)

- commitment from elected members and executives at councils (as the primary decision-makers) to make financial decisions that are in the best interest of the council in the long term.

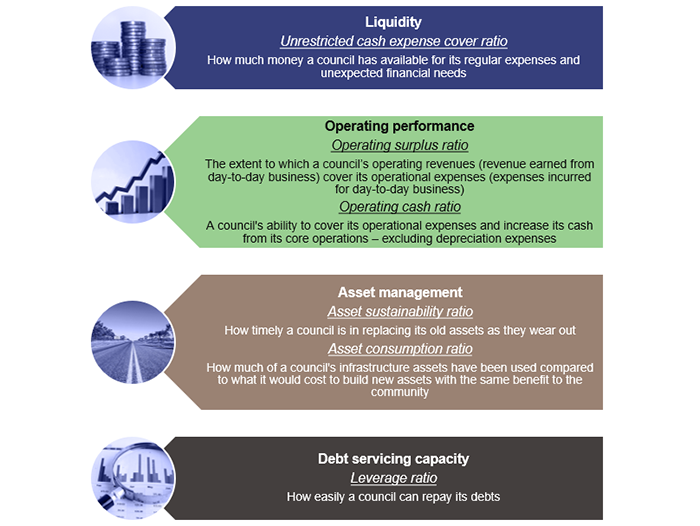

New sustainability measures provide more clarity, but an overall measure is needed

The department has introduced the Financial Management (Sustainability) Guideline (2024) (the sustainability guideline), which was implemented in the sector in the 2023–24 financial year.

The sustainability guideline includes several ratios that provide councils with meaningful ways to measure financial sustainability risk. Figure 6B provides a summary of the ratios, which councils now must report on in their financial statements.

Note: Refer to Appendix J for details of the various benchmarks for these ratios.

Queensland Audit Office.

The sustainability guideline groups councils into tiers – based on their remoteness, population, and common sustainability challenges they face. Each tier has different benchmarks assigned for the ratios.

Along with the sustainability guideline, the department has also published a financial sustainability risk framework (risk framework). The risk framework considers the above ratios and a number of qualitative measures (such as the existence of an audit committee and an internal audit function) to assess financial sustainability risk.

The risk framework does not assess all ratios collectively or assign an overall measure of risk. A recommendation was made to the department in Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023–24) to amend its risk framework, which the department accepted.

Financial sustainability measures for the year, by tiers

In Figure 6C, we summarise how many councils met the benchmark for each ratio under the sustainability guidelines. We have only included the 6 ratios that have a measurable benchmark.

Tier | Result | Operating surplus ratio | Operating cash ratio | Unrestricted cash expense cover ratio | Asset sustainability ratio | Asset consumption ratio | Leverage ratio1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tier 1 | Met | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Not met | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Tier 2 | Met | 6 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

Not met | 5 | - | 1 | - | - | - | |

Tier 3 | Met | 3 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

Not met | 4 | - | - | 3 | - | - | |

Tier 4 | Met | 5 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 9 |

Not met | 6 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | |

Tier 5 | Met | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

Not met | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

Tier 6 | Met | N/A2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 6 |

Not met | N/A2 | - | 4 | 5 | - | 1 | |

Tier 7 | Met | N/A2 | 14 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 7 |

Not met | N/A2 | - | 4 | 9 | - | 2 | |

Tier 8 | Met | N/A2 | 5 | 4 | - | 5 | - |

Not met | N/A2 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |

Total | Met | 22 | 63 | 51 | 37 | 63 | 46 |

Not met | 15 | 1 | 13 | 27 | 1 | 4 |

Notes:

The above table does not include 13 councils that had not completed their financial statements by the 31 October 2024 statutory deadline.

1 Only applicable for councils that have borrowings.

2 Councils in tiers 6–8 do not have a benchmark for measuring their operating surplus ratios.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office, from councils’ certified financial statements available 31 October 2024.

Councils’ operating results have been affected by the timing of federal government grants

The financial assistance grants (FA grants) that local government receive are ‘untied’ grants, which means they do not have any conditions attached to them, and councils are free to use them for any purpose they deem fit. Accordingly, under the Australian accounting standards, these grants are recognised as revenue in the year in which they are received.

The total amount of funding, the main basis for the formulas for allocation, and the timing of the payment is determined by the Australian Government. The Queensland Government facilitates the payment.

Historically, councils have received their FA grants each year in the following manner:

- 50 per cent of their funding for the year has been received in the year the grant relates to

- 50 per cent has been received as an advance of what they are entitled to for the next year.

At the direction of the Australian Government, in the financial years 2021−22 and 2022−23, councils received 125 per cent of their FA grants in advance (as shown in Figure 6D).

![Legend: current year’s funding received; next year’s funding received. 2019-20: 50%; 50%. 2020-21: 50%; 50%. [2021-22: 50%; 75%. 2022-23: 25%; 100%. Councils effectively received 125% of their grant funding.]. 2023-24: 0%. No funding received.](/sites/default/files/2025-04/Local%20government%202024_Figure%206D_0.png)

Queensland Audit Office.

Over several years we have been highlighting the uncertainty over the timing and amount of FA grant funding that would be provided in advance each year for councils.

In the 2021–22 and 2022–23 years when councils received 125 per cent of their FA grants, more councils made operating surpluses. However, in 2023–24, when the sector did not receive any FA grants, it resulted in a significant number of councils incurring operating deficits. This is shown in Figure 6E.

We have also shown in Figure 6E how many councils would have generated operating surpluses and incurred deficits if they had received 50 per cent of the funding in advance and 50 per cent of the funding in arrears, as they have for many years prior to the 2021–22 financial year.

Maintaining liquidity is necessary for councils that do not generate enough own-source revenue

Operating revenue (also known as own-source revenue) is revenue generated by the day-to-day operations of a council’s business, such as rates, fees, and charges.

Operating expenses are incurred in the day-to-day operations of a council’s business, such as employee expenses.

Operating surplus is the excess of operating revenue over operating expenses.

Councils need to generate operating surpluses in the long term (for example, over a period of 5 or more years) in order to be able to fund unforeseen future expenditure. To some extent, it can also contribute to their capital needs, such as building assets for their community. Generating a surplus is difficult for some councils. In some instances, it is impossible for those with a low capacity to raise own-source revenue.

The department has recognised these challenges and has included additional ratios in the sustainability guideline to measure the financial sustainability risk for these councils. One of these ratios is the unrestricted cash expense cover ratio. It is an indicator of a council’s ability to meet its ongoing and emergent financial demands based on its current operating levels.

Councils in tiers 5–8 (47 councils) are generally less able to generate sufficient operating revenue throughout the year. As such, they need to make sure they are careful in their spending and maintain sufficient cash reserves. Accordingly, the sustainability guideline prescribes a benchmark of 4 months of cash reserves for councils in these tiers.

As of 31 October 2024, 34 of the 47 councils in tiers 5–8 had completed their financial statements. Of these, 11 councils (approximately 32 per cent of those that completed their financial statements) did not meet their benchmark for the unrestricted cash expense cover ratio.

Of the 11 councils that had lower than required cash reserves, 10 also incurred operating losses in most of the 5 financial years from 2019–20 to 2023–24, including those years in which they received 125 per cent of their FA grants.

If councils consistently incur operating losses and do not have sufficient cash reserves, they face the risk of not being able to pay their operating costs such as salaries and wages. Strong cash management processes will ensure they have enough liquidity to meet their planned expenditure.

Opportunities for councils – good cash management processes Good cash management processes ensure that councils maintain enough cash balances to meet their planned operational expenses and any unforeseen expenditure that may arise. Some principles of good cash management are:

|

Investment in community assets

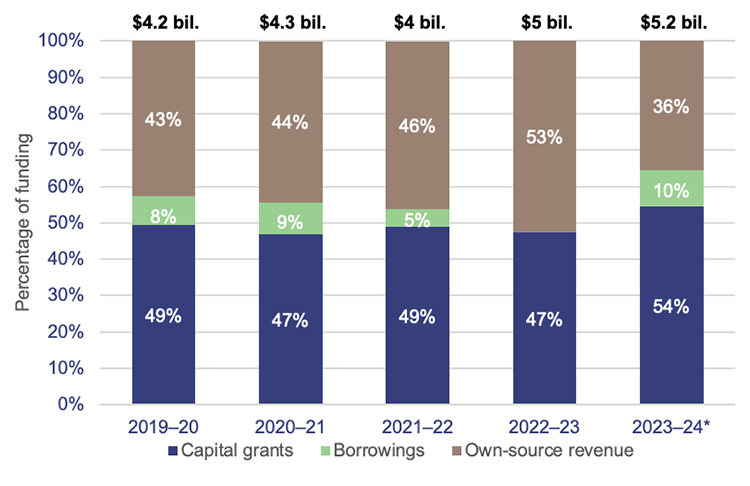

Each year, councils invest significant amounts to maintain existing assets and build new ones for their community. This year, the sector invested $5.2 billion (2022–23: $5 billion). This is the highest expenditure for the sector in the last 5 financial years, and it has been funded from grants, own-source revenue, and borrowings.

Note: * For 2023–24, we have included the financial information of 13 councils using their last available certified financial statements, as they had not completed their 2023–24 financial statements by the 31 October statutory deadline.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from councils’ certified financial statements available as of 31 October 2024.

Although expenditure over the last 2 years has been approximately 20 per cent higher than in the 3 years before, this is largely due to the increased cost of procuring materials and labour. It is not necessarily because council assets are being maintained to a higher level.

This can be demonstrated through the asset consumption ratio, which measures how much of an asset’s value is yet to be consumed. The new sustainability framework recommends that, for assets to meet community needs, the asset consumption ratio should be greater than 60 per cent.

As of 30 June 2024, of the 64 councils that had their financial statements completed:

- 7 councils did not meet their benchmark, meaning while their assets still probably deliver the services, the quality of service would be of a lower standard

- 16 councils had an asset consumption ratio of between 61 per cent and 65 per cent, meaning their assets are at risk in the short term of not providing the appropriate level of service.

The sustainability framework currently requires the asset consumption ratio to be reported in aggregate for all types of infrastructure assets.

Although this may provide an approximate indication of the service levels of council assets, some council asset classes (for example, road assets) may be in a better condition than others.

This would especially be the case in some of the flood-prone zones of the state (most of which are rural and remote councils) that repair their roads frequently – some do it every year. This means their roads would have a strong asset consumption ratio while other asset classes may not – meaning their overall ratio may meet the benchmark set under the sustainability guideline, but some of their assets may not be providing the level of service that they should.

An alternate and more useful way to measure the asset consumption ratio would be by asset type (for example, by road assets, water assets). This would provide councils with a better mechanism for assessing their assets by type and would show them when these assets will need renewal or replacement.

It could also help councils have timely conversations with the department regarding funding for replacement or major repairs, if needed.

Recommendation for the department Amend the sustainability guideline to include the asset consumption ratio for each asset class 5. We recommend that the department amends the sustainability guideline so that councils are required to calculate and report on the asset consumption of each asset class in their financial statements. |

The sector’s water infrastructure assets need immediate attention

We recently tabled Managing Queensland’s regional water quality (Report 7: 2024−25), in which we identified that well-maintained infrastructure is essential to delivering safe drinking water. As an indicator of whether councils’ water infrastructure assets were of a standard to provide quality drinking water, we calculated the asset consumption ratio for water assets across all councils.

We found 35 councils that have water infrastructure assets (69 councils own water infrastructure assets in Queensland) had an asset consumption ratio of lower than 61 per cent. This is approximately 49 per cent of the councils that own water infrastructure assets. This may be an indication that these councils’ water infrastructure assets are at a risk of not providing the appropriate level of service to their community.

Figure 6G provides a breakdown of the asset consumption ratio by councils for water infrastructure assets.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from councils’ certified financial statements available as of 31 October 2024. (Refer to Appendix B for more information.)

Among councils that have a lower asset consumption ratio for their water infrastructure assets, 22 have a population of 10,000 or more (based on the 2021 census data published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics).

Councils that have a low asset consumption ratio for their water infrastructure assets should consider undertaking an assessment of their water infrastructure assets. They should also compare the age of these assets to their asset management plans and see if the plans need to be updated.

This will help them determine at what point in time they will need to renew or replace their water infrastructure assets, and it will allow them to start planning for the funding now.

Recommendation for councils Review the asset consumption ratio for water infrastructure assets and determine what action is required 3. We recommend all councils review the asset consumption ratio for their water infrastructure assets. Where the ratio is below 60 per cent, councils should assess the need for repairs/renewals to their water infrastructure assets that will reinstate these assets to a level that provides the appropriate level of service to their community. |

Update on entities that missed the deadline for last year’s report

At the time we compiled Local government 2023 (Report 8: 2023−24), 14 councils had not completed their financial statements. Subsequently, 11 are now completed.

Of these 11 councils, 7 councils combined incurred operating losses of $13 million for the 2022–23 financial year. All 7 of those have incurred operating losses in at least 2 of the last 3 financial years.

Local government dashboard 2024

Our interactive map of Queensland allows you to search and compare councils to view their financial performance and sustainability indicators. This tool includes information on revenue, expenses, operating costs, assets, liabilities and sustainability indicators.

![Actual operating results: Legend: number of councils generating surpluses; number of councils incurring deficits; unable to conclude on performance. [2021-22: 35; 42; 0. 2022-23: 47; 26; 4. Councils received 125% of their grant funding]. 2023-24: 12; 52; 13. Adjusted operating results if 50% advance payment received each year: Legend: number of councils generating surpluses (adjusted); number of councils incurring deficits (adjusted); unable to conclude on performance. 2021-22: 28; 49; 0. 2022-23: 32; 41; 4](/sites/default/files/2025-04/Local%20government%202024_Figure%206E_0.png)