Overview

Safe, secure, and reliable drinking water supports the wellbeing of Queensland’s regional communities. Delivering it to our taps is a complex process that requires well-maintained infrastructure, skilled operators, and constant monitoring.

Tabled 18 December 2024.

Report summary

Delivering safe drinking water to our taps is a complex process. It requires well-maintained infrastructure (including treatment plants, filters, and pipes), skilled operators, and constant monitoring.

This audit examines how effectively 4 regional and remote councils supply safe drinking water to their communities. It also examines how the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department) regulates drinking water quality across the state.

Providing safe drinking water

In regional Queensland, councils are mostly responsible for providing drinking water to their communities.

The 4 councils we audited had water quality management plans, but 3 of them were found to be non-compliant with their plans. Independent audits found issues with monitoring programs, maintenance and inspection activities, record keeping, and reporting water incidents to the regulator. Two of the councils we audited had tested their emergency response plans for responding to high-risk events, such as natural disasters and equipment failure. The other 2 had not.

The 4 councils had measures in place to reduce the risks to the quality of their drinking water. But some of these risks are still higher than the councils would like, creating potential for a hazard to occur. Two councils have had improvement actions for high-risk areas ‘pending’ for up to 4 years. These pending improvements are a mix of items like maintenance, training, standard operating procedures, and larger infrastructure upgrades. These 2 councils could improve their oversight of these risks, improvement actions, and the recommendations identified by independent audits.

Those charged with governance must be satisfied the council has implemented their management plans and is performing the activities to keep their communities safe. Improved longer-term planning would enable councils to ensure access to a capable workforce and to better manage their infrastructure needs.

Regulating drinking water quality

The department is the main regulator for drinking water. It registers water service providers (which are mostly councils in regional Queensland), approves their management plans, and monitors their compliance, along with delivering support and education to councils.

The department’s regulatory program involves assessing council risk and planning, conducting its monitoring and enforcement activities, and reporting on compliance. It also monitors and responds to water incidents reported by councils. The department is yet to effectively balance its need to respond to incidents, to fully deliver its compliance program, and to be timely with reviewing independent audits and councils’ annual reports. It has started workforce planning to enable it to better staff these activities and to assist in identifying and addressing potential problems earlier.

The department is aware of the challenges and associated risks many councils face. It has started projects to improve council capability and identify infrastructure needs. However, it had not formalised how it would collaborate with other agencies and across councils. On 1 November 2024, the government redistributed the water regulation and local government functions into the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers. This change provides an opportunity for these 2 functions to work more closely together to help coordinate and prioritise resourcing and infrastructure planning.

The department’s guidelines for managing drinking water align with the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines. However, the department has not mandated the health-based targets in these guidelines due to the potential costs and the issues some councils are facing with infrastructure and staffing. Some larger councils, who have the necessary resources, are voluntarily adopting these targets, as there are many benefits to doing so.

1. Audit conclusions

The Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department) and councils face complex challenges in providing safe drinking water.

The department and councils are taking steps to ensure communities have access to safe drinking water, but some areas still need improvement. Queensland has not experienced an identified outbreak of waterborne diseases in the last 10 years, but the department and entities must remain ever vigilant. Water incidents and boil water alerts are still common, indicating there are areas where services could be improved.

The 4 councils we audited varied in their ability to consistently meet the standards required by drinking water legislation and to address key risks to their water quality, particularly for the smaller 2 councils. These councils have long outstanding improvement needs, which range from routine maintenance, standard operating procedures, and training staff, to larger more costly needs, like upgrading infrastructure.

Workforce and infrastructure challenges can be a cause or contribute to non-compliances and water incidents. Better planning will help councils to address workforce and infrastructure challenges and more effectively deliver drinking water to the community. Two of the 4 councils need to improve their readiness to respond to high-risk events and oversight of risks, improvement actions, and compliance with their management plans.

The department’s oversight and regulation of drinking water providers has increased over the last 10 years. Still, there are areas it can continue to improve to increase the effectiveness of its regulatory program. These include clarifying how it prioritises its regulatory efforts based on risk, better matching its workforce capacity to the demands of responding to incidents, and delivering its compliance program in full. Improving the data it collects from councils could better help the department assess if its activities are helping improve water quality or not.

The department can further support high-risk councils to improve their capabilities and help them in their planning activities. It could strengthen coordination across all levels of government, including by sharing information it has gathered through regulatory activities and projects, such as the Urban Water Risk Assessment project. The recent change merging the government functions overseeing local government and water regulation into the new department presents an opportunity for stronger integration of the department’s response and closer collaboration to further enhance council workforce and infrastructure planning.

Addressing these challenges will take time, but is necessary to ensure the continued long-term health and safety of our communities.

2. Recommendations

We have developed the following recommendations for all councils, and for the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers.

| Chapter 4: Providing safe drinking water |

We recommend all councils: 1. assess their record keeping of essential activities for managing drinking water quality to ensure they are

2. ensure appropriate oversight of compliance with management plans, risks to drinking water quality, improvement actions, and recommendations from independent audits 3. assess and address identified capability and expertise gaps 4. test their emergency response plans periodically for high-risk events, and train staff in how to respond. We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers: 5. improves coordination with its water regulation and local government functions, and across agencies by developing mechanisms to coordinate and share information, and promote workforce and infrastructure planning with providers 6. develops a pathway for adopting health-based targets by

|

| Chapter 5: Regulating drinking water quality |

We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers: 7. improves its risk-based approach to assessing and managing providers by

8. enhances its workforce planning to ensure it has sufficient resources to deliver its compliance activities, meet the demand for responding to incidents, and review the providers’ audit reports and annual reports in a timely manner 9. evaluates its response to non-compliance and assesses the effectiveness of outcomes from its actions 10. enhances the data it collects on drinking water quality and implements a process to monitor and report on water quality 11. improves how it measures its performance and reports externally by

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from entities are at Appendix A.

3. Drinking water in Queensland

This chapter provides an overview of the drinking water responsibilities of councils (as water service providers) and state entities. It also details how drinking water is provided and explains what ‘water quality’ means.

How is drinking water provided in Queensland?

Outside of South East Queensland, 72 providers supply drinking water, and 65 of these are councils. The other providers include 2 water boards, one river commission, 3 government owned corporations, and one private company.

The providers must be registered and have an approved drinking water quality management plan with the regulator, the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers. Some councils manage multiple water schemes to supply towns in their local government areas.

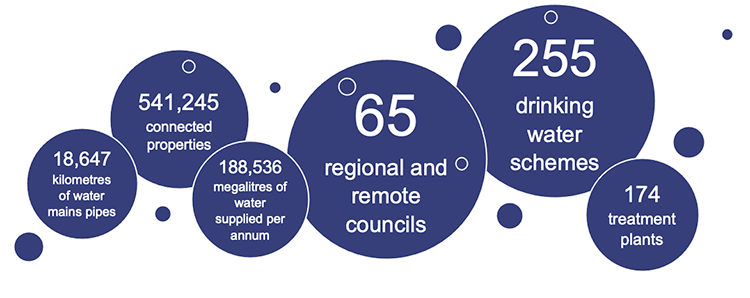

The 65 councils operate 255 schemes; 42 of them operate more than one scheme, and of those, 5 manage 10 or more schemes. Figure 3A details key statistics about providing drinking water in regional Queensland.

Note: All data is self-reported by councils except for the number of councils and schemes which is based on the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers’ data.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers’ ‘Urban Water Explorer’ website.

How is drinking water regulated?

As the state’s primary regulator of the management of water resources, the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department) regulates drinking water under the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008 (the Act).

Under the Act, the department is responsible for the safety and reliability of drinking water. It does this by:

- registering providers

- ensuring providers comply with the Act – through monitoring and enforcement activities

- delivering support and education to providers.

The Act also gives the department emergency powers to operate drinking water infrastructure if a provider is unable to supply safe drinking water. It can use these powers as a last resort.

The department’s Strategic Plan 2023–2027 includes an objective that says: ‘Lead water resource management to achieve sustainability and public safety’. It aims to do this by developing and implementing legislation, policies, and programs that provide community confidence and minimise risks to drinking water.

It has a range of approaches for addressing the risks, including collaborating with other departments to assist providers in meeting their funding and capability needs, delivering drinking water programs and projects, and providing policy advice to government.

Queensland Health regulates some aspects of drinking water under the Public Health Act 2005 and the Public Health Regulation 2018. It gives health advice when a drinking water incident (such as an equipment breakdown or identification of contaminants) occurs. It also sets health limits for water quality testing, like Escherichia coli (E. coli) limits, and has the power to direct providers to take certain actions when there is a risk to public health.

Who we audited

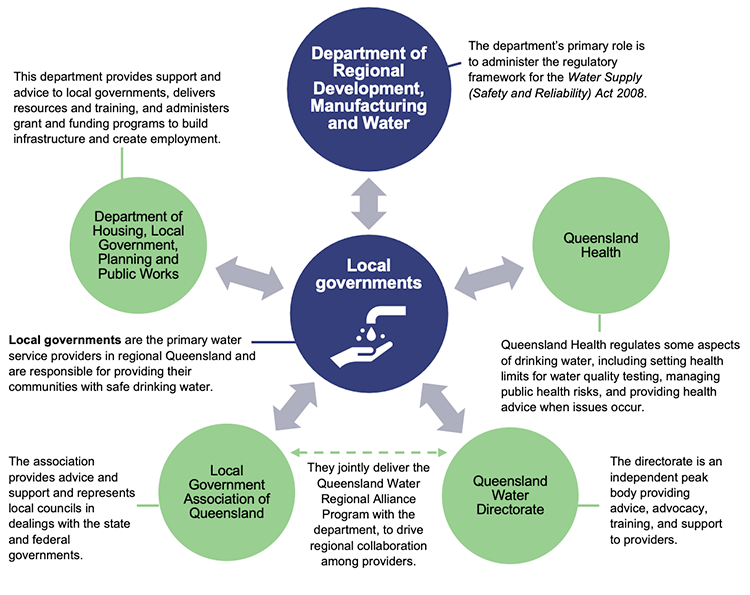

Delivering safe drinking water requires a collaborative effort between councils, the department (as the primary regulator), other agencies including Queensland Health, and advocacy bodies.

We audited the previously named Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water and 4 councils. The findings in this report reflect the departmental arrangements before 1 November 2024.

We have outlined the scope of our audit in Appendix B.

Figure 3B shows the roles and relationships of entities with responsibilities in the drinking water sector before the 1 November 2024 changes.

Note: Blue circles show the entities we audited.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

Our audit did not assess the role or functions of the Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works.

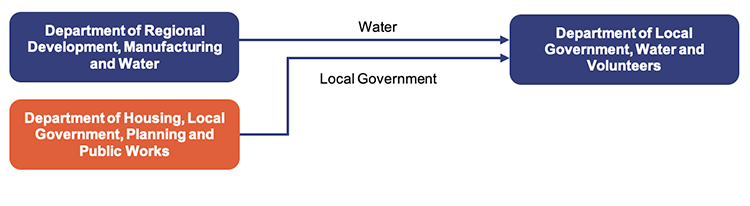

On 1 November 2024, the government announced a machinery of government change, which redistributed the functions of water regulation (previously in Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water) and local government (previously in Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works) into the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office.

What does ‘water quality’ mean?

The Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (the Australian guidelines) specify several characteristics of quality drinking water. These fall into broad categories of safety and aesthetics, including appearance, taste, and odour. The Australian guidelines set safety limits for microbial, physical, chemical, and radiological characteristics.

Microbial characteristics refer to microorganisms that include bacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), viruses, helminths (parasitic worms), or protozoa such as Giardia. These can be caused by animal waste runoff from the land surrounding the sources of surface water.

Physical characteristics are the appearance, taste, odour, and feel of water. Physical characteristics include turbidity (cloudiness), pH, and temperature. While these are not unsafe, elevated levels can impact on the effectiveness of water treatment processes.

Chemical characteristics include organic compounds and inorganic compounds (such as pesticides).

Radiological characteristics can occur naturally in the environment (for example, uranium, and thorium) or can arise from human activities (for example, medical or industrial).

Exceeding health limits, especially microbial limits, can lead to outbreaks of waterborne diseases. This can have serious health consequences and affect large portions of the community. If water is not safe to consume directly from the tap, a provider may issue a ‘boil water alert’ as a precautionary measure to protect public health. The alert must remain in effect until the provider, Queensland Health, and the department are satisfied there is no longer a public health concern.

The department’s records show that 111 boil water alerts have been issued by 35 providers in regional Queensland over 3 years to 30 June 2024. Of these alerts, providers resolved 108 with an average duration of 62 days.

Queensland has not had an identified major outbreak of waterborne diseases in the last 10 years. However, the risk of diseases is present, requiring proper management of water services or readiness to respond to emergencies, like major weather events.

International incidents serve as a reminder that improper management of water services can have disastrous outcomes. New Zealand’s 2016 Havelock outbreak, detailed in the following case study (Figure 3D), is an example.

| Waterborne disease outbreak in New Zealand |

|---|

The outbreak In 2016, following a significant rain event, contaminated water entered an unconfined bore (a shallow bore that is not closed off from surface water) in Havelock North (New Zealand). The contamination was likely caused by animal faeces from surrounding farmland flowing into a pond that fed the bore. The contaminated water was pumped into the community, and water testing 7 days later identified Escherichia coli (E. coli) in the water supply. In response to the test results, the regional council pumped chlorine through the system, flushed the water network, and issued a boil water notice. Several cases of gastroenteritis had already been diagnosed in the community. It is estimated that 5,500 of the town’s 14,000 residents became ill, and 45 were subsequently hospitalised. The district health board linked the outbreak to 4 deaths. The cause In 2017, the New Zealand Government’s inquiry into the outbreak found the regional council failed to inspect the quality of the bores, assess the risk of contamination, and perform required maintenance, and had inadequate emergency response plans. The inquiry also found the district health board assessor incorrectly assessed the supplier as compliant and failed to have a hands-on approach, given there had been many E. coli detections prior to the outbreak. |

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Australian Water Association website.

4. Providing safe drinking water

In this chapter, we report on how 4 regional and remote councils implemented drinking water quality management plans, responded to incidents and hazardous events, managed risk, and improved their performance. The councils were:

- Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council

- Fraser Coast Regional Council

- Western Downs Regional Council

- Winton Shire Council.

The 4 councils we audited may not be representative of all councils in Queensland, so the results cannot be extrapolated to all. However, we recommend that all councils consider our findings and recommendations to determine the extent to which they may be relevant to them.

How effective are the councils in implementing their plans for drinking water?

Each of the 4 councils we audited had an approved drinking water quality management plan (management plan). These are risk-based plans on how councils manage the safety of the drinking water they supply to customers, and include details on operational and maintenance procedures, water quality monitoring, and improvement plans.

Councils engage independent and certified water specialists to audit the management plans to ensure they accurately describe the water service and comply with conditions. The auditor also assesses whether monitoring data given to the regulator is accurate. The Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department) requires these audits every 4 years.

All 4 councils were up to date with their audits. These audits identified 12 instances across 3 of the 4 councils not complying with their management plans.

Figure 4A summarises the instances of non-compliance identified by independent audits at Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council, Western Downs Regional Council, and Winton Shire Council.

|

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from independent audits of drinking water quality management plans at Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council, Western Downs Regional Council, and Winton Shire Council.

The department reviews these audits and records the non-compliances. In Chapter 5, we explain the department is taking more than 200 days to review these reports and the types of actions it takes with councils to bring them back into compliance.

Our visits to these councils found some of the issues identified by independent audits have not yet been addressed. At Winton Shire Council, there was a lack of standard operating procedures to help ensure the correct and consistent execution of daily tasks within the drinking water service.

Management plans ensure the safety of drinking water supplied to councils' customers. However, the councils need to follow through on their proposed activities and improve their record keeping. Records management is important for effective drinking water quality systems because it ensures a structured approach, protects knowledge, and shows responsibility for actions.

Recommendation 1 We recommend all councils assess their record keeping of essential activities for managing drinking water quality to ensure they are:

|

The exception was Fraser Coast Regional Council, whose recent independent audit did not identify any non-compliance. This council undertakes more frequent independent water quality audits as part of obtaining accreditations in quality and safety for its water service. These audits assure those accountable that the council’s water operations and systems are functioning properly and in accordance with the management plans approved by the department.

Are the councils effectively managing risks and improving performance?

As part of the department’s guidelines for councils’ management plans, the councils must:

- identify hazards and hazardous events that may affect the quality of water

- assess the risks posed by the hazards

- demonstrate how they will manage the risks.

Councils manage the risks posed by the identified hazards and hazardous events either through existing preventative measures or additional proposed measures. Existing measures may include routine maintenance, treatment processes, or restricting access to water catchment areas.

Additional proposed preventative measures may include replacing equipment, undertaking significant infrastructure upgrades, addressing skills gaps, or reviewing and improving monitoring practices. Councils include these measures in their improvement programs, which form part of the management plan.

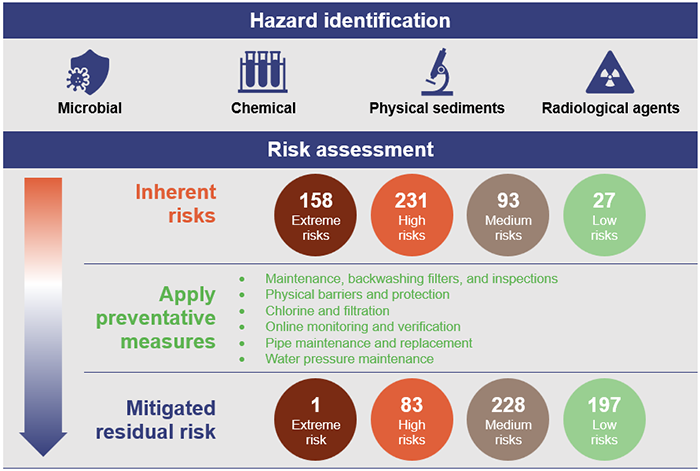

In their 2022–23 management plans, the 4 councils collectively identified 158 extreme and 231 high inherent risks, reflecting the significant risks and hazards that councils must manage to make their water safe. The inherent risk is the level of risk in place before any control measures are applied.

Figure 4B summarises the risk assessments in the management plans of the 4 councils we audited. It details the types of hazards, the inherent risks they have identified, preventative measures they are able to implement, and the mitigated residual risk level after the preventative measures have been applied.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the drinking water quality management plans of 4 councils.

Councils are responsible for setting their acceptable risk levels (the level of risk that councils are comfortable with) and applying preventative measures to reduce their inherent risks to this level. Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council's, Western Downs Regional Council's, and Winton Shire Council's acceptable risk levels are low and medium, whereas Fraser Coast Regional Council only accepts low risks.

After applying preventative measures, the councils had reduced most of their risks into lower categories. However, there were still one extreme and 83 high risks outside the acceptable level. These councils and the department tolerate these risks until they can implement new preventative measures.

In their improvement programs, the councils proposed new preventive measures to further reduce these risks and assigned a priority to implementing those measures. These improvement items need to be implemented to bring this risk down to acceptable levels.

Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council and Winton Shire Council have improvement actions for high-risk areas that have been ‘pending’ for up to 4 years. These actions range from undertaking maintenance, developing standard operating procedures, and training staff, to more costly items like upgrading infrastructure. They told us they were unable to fund these actions, and they lacked the resources needed to plan and implement the activities. In October 2024, the Australian Government announced that it would jointly fund $26 million of Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council’s upgrades that would address some of these high-risk areas.

Fraser Coast Regional Council and Western Downs Regional Council were more effective at implementing their improvement items for high-risk areas.

Councils report annually to the department on their progress in implementing items in their improvement programs. They publish these reports on their websites, providing transparency to their communities.

Some of the councils need better governance of drinking water risks

The council’s executive management is responsible and accountable for effectively managing drinking water services and performing activities to keep its community safe.

Of the 4 councils we examined, Winton Shire Council lacked evidence that its executive management had oversight of drinking water risks, improvement actions, and recommendations from independent audits. Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council and Winton Shire Council lacked evidence that their governance groups, such as councillors or audit committees, were monitoring progress of these activities.

Many of the outstanding improvement items and recommendations from independent audits at these councils are not costly to implement, but they are important to ensuring water quality. They include having operating procedures, providing internal training, or performing testing according to their management plans.

Management and governance groups can do more to ensure they are informed, monitoring these items and tracking progress. Audit committees could also assist management oversight of timely resolution of audit issues.

Recommendation 2 We recommend all councils ensure appropriate oversight of compliance with management plans, risks to drinking water quality, improvement actions, and recommendations from independent audits. |

Addressing workforce and infrastructure challenges

Each council needs to have capable staff and well-maintained, fit-for-purpose infrastructure to provide safe drinking water to its community. Developing and retaining access to appropriate expertise, and maintaining infrastructure can be challenging for regional councils. Strengthening workforce and infrastructure planning could address some of the causes of non-compliance found in independent audits and reduce the number of water incidents.

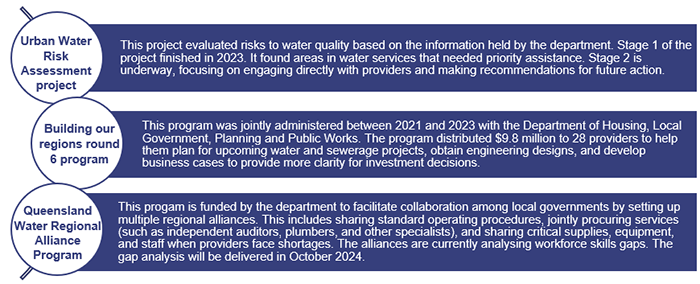

Recognising that regulation alone will not address these issues, the department has started several initiatives to evaluate risks across the sector, improve collaboration, and assist councils with their infrastructure planning.

Figure 4C shows the department’s current initiatives for identifying and addressing councils’ infrastructure and capability challenges.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers’ documents.

We did not audit the effectiveness of these projects and programs. However, feedback from councils, the department, and stakeholders was positive on these initiatives.

Growing workforce capability

Councils need access to appropriately skilled and trained people, as they have a major impact on drinking water quality and public health. The department, councils, and other stakeholders raised concerns with us about the challenges of maintaining workforce capabilities in regional and remote communities. Three of the councils we audited had vacancies in their water operations teams and they relied on consultants to prepare their management plans.

The department has the authority to set out and enforce mandatory qualifications or necessary experience for a service operator working on drinking water. It has not done so because some councils may not be able to meet these requirements. This means that these councils and the department are accepting a higher level of risk. Both Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council and Winton Shire Council have identified untrained staff as a high risk.

Currently only 2 registered training organisations provide relevant courses. TAFE Queensland withdrew from the National Water Training Package (the main training package for onsite workers) in 2022. Some courses are only delivered when there are enough participants, leaving potential trainees on a waiting list unable to obtain timely training. Travel is usually required, as training is best delivered face-to-face due to the practical nature of the qualification. The geographical remoteness of some councils increases the costs. Also, some of those councils may only have limited numbers of water operators, making it difficult for them to take time out to attend training.

To support formal training, councils will need to ensure that in-house training gives staff a knowledge base to operate systems, follow the management plan, and make effective decisions. They should understand their skills gaps in applying their management plans and asset management, which is important for long-term planning of their infrastructure needs.

Councils should also seek opportunities to draw on other resources and assist neighbouring councils. The Queensland Water Regional Alliance Program provides a forum for councils to collaborate, share best practices, and address common challenges in regional water management.

Recommendation 3 We recommend all councils assess and address identified capability and expertise gaps. |

Better long-term infrastructure planning

In our audit, Improving asset management in local government (Report 2: 2023–24), we made several recommendations to improve gaps in asset management across all councils through stronger governance, better data, and improved asset management capabilities. Councillors and senior management need to know key details about their assets when they are making decisions.

Where councils’ improvement programs involve large infrastructure upgrades and replacements, they need to include them in their asset management plans, so they can effectively budget and consider funding options. This can also help councils to be better prepared to apply for project funding.

The department told us it provides informal feedback to funding agencies (such as to the previous Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works) on local government applications on an ad hoc basis. There was no requirement for it to have input into the funding allocations.

The Urban Water Risk Assessment project provides the department with an opportunity to support councils to develop plans that identify critical infrastructure needs and consider their funding options. Using these plans and information the department has gathered through regulation activities could help inform other funding agencies on what type of grant programs are needed and who has the most urgent needs.

With the recent machinery of government change merging the water regulation and local government functions into one department, there are greater opportunities to leverage these plans, share information, and coordinate more effectively in the newly formed department.

Recommendation 5 We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers improves coordination with its water regulation and local government functions, and across agencies by developing mechanisms to coordinate and share information, and promote workforce and infrastructure planning with providers. |

Most councils are not ready to implement health-based targets

In 2009 the Australian Government’s National Health and Medical Research Council (the national council) released a discussion paper introducing health-based targets. The World Health Organisation and the national council endorsed health-based targets for drinking water quality in 2022, when the national council added the targets to the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (Australian guidelines).

Health-based targets are a quantitative measure of drinking water quality. They involve an assessment of source water risks, treatment requirements, and microbial safety.

Assessing these risks helps in identifying the appropriate barriers and preventative measures required to treat water to make it safe. For example, some microorganisms may require more advanced filtration or additional treatment such as ultraviolet light.

Health-based targets involve:

- defining a benchmark for water safety

- assessing the level of contamination in source water and assigning a source water category

- assessing the level of treatment needed, based on the category of source water

- implementing treatments to ensure the benchmark for safety is met.

After initiating an independent review in 2019 to assess potential issues with implementing the targets, the department decided against formally adopting them in 2022. The review found that many councils would struggle to implement the targets due to the capital investment required to address shortfalls in their existing treatments of microorganisms. The review also raised concerns about the ability of some councils to acquire the technical expertise for assessing their performance against the targets.

While the department communicated its decision to not adopt the targets to councils through workshops and at a conference, some councils are confused about the longer-term direction, given that the targets have been incorporated into the Australian guidelines. The department has also included minor aspects of the targets’ risk assessment in the 2022 update to its guidelines for drinking water quality management plans (which councils must complete).

Some larger and medium councils (with more resources than other providers) are already planning for future infrastructure that enables them to meet the targets. They have assumed that they will eventually be adopted. Both Fraser Coast Regional Council and Western Downs Regional Council have factored health-based targets into their planning.

The department anticipates that smaller councils will require substantial support and investment to achieve the benchmark standard for water safety. It is also concerned that the transition to the targets could divert resources from managing current operations, leading to unintended outcomes.

It has not yet assessed the regulatory impact or identified the costs and benefits of fully implementing the targets and the public health risks of not adopting them. An impact assessment could also consider the options for implementing the targets. The department will also need to develop a clear implementation plan and time frame for fully adopting the targets.

Recommendation 6 We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers develops a pathway for adopting health-based targets by:

|

In October 2024, the National Health and Medical Research Council commenced consultation on proposed changes to guideline values to polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These synthetic materials have properties which impact the environment and health of the public if consumed in drinking water.

The proposed changes, which are based on expert health advice and research, are intending to set lower limits for permissible PFAS levels detected in drinking water. While not yet mandatory, a change to these limits could require providers to assess whether their existing systems will meet the new standards if they are implemented. Consultation on the PFAS guidance closed on 22 November 2024.

How effectively do the councils respond to incidents?

Councils must report all incidents, such as an equipment breakdown or identification of contaminants, to the department. Reporting incidents promotes a culture of continuous improvement and safety.

Incidents can have a potentially adverse impact on drinking water quality, and they must be reported to the department. They include:

- a detection of Escherichia coli (E. coli)

- an exceedance of a health guideline value in the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (Australian guidelines)

- a detection of a water quality characteristic with no health guideline value in the Australian guidelines

- an event that the service provider cannot manage within its existing processes and/or that may impact on the health of consumers.

Non-compliance occurs when a provider does not report an incident, fails to comply with requirements in the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008, or acts outside the processes defined in its approved drinking water quality management plan.

Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council, Western Downs Regional Council, and Winton Shire Council did not report all recorded incidents to the regulator between July 2021 and June 2023. These included incidents identified in councils' independent audit reports and by the department from reviewing annual reports or water quality testing.

Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council and Winton Shire Council did not follow the requirements of their management plans when responding to incidents. In some cases, they have not taken corrective actions to resolve the incidents, such as preparing standard operating procedures and providing training. This contributed to the department issuing Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council with an infringement notice following a repeat of an incident where council had not taken corrective actions.

The councils need to test their preparedness to respond to incidents

Effective incident response plans, required by legislation, allow for a timely, coordinated, and controlled response, which is crucial to minimising potential public harm.

All 4 councils have incident response plans, but Winton Shire Council and Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council have not tested their plans. This means they do not know how well they will work, and they may not be as prepared as they could be to respond in an emergency.

For example, Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire Council’s treatment plant recently malfunctioned and drained its water reserves. The water operators did not respond to alarms, and the council was unaware of the loss of supply until the hospital notified the council that it had run out of water. Appropriate testing of response plans may have minimised the impact of this event.

Testing of incident response plans can also improve council preparedness to respond to water quality impacts from severe weather events. Councils must prepare for these events, to enable them to respond quickly and reduce the risk of harm to the communities they serve.

Recommendation 4 We recommend all councils test their emergency response plans periodically for high-risk events, and train staff in how to respond. |

5. Regulating drinking water quality

In this chapter, we detail how the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers (the department) identifies and manages risk. We assessed how the department plans and prioritises its work to ensure the safety of drinking water services. We assessed how effectively it manages incidents and monitors and reports on its performance and the quality of drinking water.

Before the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008 (the Act) was enacted, Queensland Health regulated drinking water under the Public Health Act 2005. However, this legislation did not have a regulatory framework to manage drinking water service providers (providers).

Since 2008, the department has gradually increased its oversight and regulation of providers. Two key components of this regulation are approving the drinking water quality management plans (management plans) produced by providers and holding providers accountable for complying with their plans.

Figure 5A outlines the timeline of key changes to drinking water regulation.

Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008 (the Act) was enacted, establishing a regulatory framework for new and existing water service providers.

Providers must have an approved drinking water quality management plan. This was implemented in a staged approach with education and support from the department.

Providers required to have an independent audit against their responsibilities under the Act.

The department developed and implemented a risk assessment framework.

The department increased regulatory compliance enforcement and implemented an information management system to manage non-compliance and incidents.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers.

Does the department use risk to prioritise regulatory efforts?

The department has developed a process to assess the risk that providers will not comply with their legislative obligations. However, the department does not sufficiently document the rationale behind the assessments, and it is unclear how it uses the risk assessment to prioritise activities in its compliance program.

The department plans to evaluate providers annually and allocates risk ratings based on a set of targeted questions that consider the likelihood and consequence of public harm. However, it did not complete the 2022–23 risk assessment. Instead, it commenced the 2023–24 risk assessment, which is yet to be finalised.

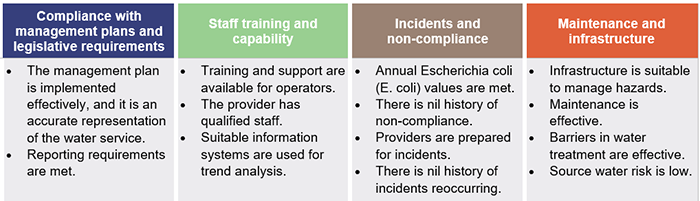

Figure 5B summarises the criteria that the department uses to determine the providers’ risk.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office from the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers’ compliance risk assessment.

In its most recently completed risk assessment in 2021–22, the department identified 15 out of 72 regional providers as high risk. It is unclear how the department uses the risk assessment to prioritise activities in its compliance program. The risk assessment needs to be updated to ensure the department is prioritising its resources to areas with the greatest risk.

The department aims to help move high-risk providers into a lower risk category through targeted support and monitoring activities. It could help clarify how it prioritises these high-risk providers by developing specific support plans targeted to the providers’ individual needs.

The department’s risk assessment applies a risk rating to each provider. However, it does not document its justifications for the ratings. Doing so would provide transparency and ensure assessments are applied consistently. It could also provide information about providers’ changing risk profiles.

Recommendation 7 We recommend the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers improves its risk-based approach to assessing and managing providers by:

|

Does the department plan its work and monitor compliance?

The department outlines its planned compliance activities for drinking water regulation in its annual work plan, with a milestone or performance target for each activity. The work plan is an internal document which includes a range of proactive and reactive activities.

In 2022–23, the department achieved its targets in 18 out of the 27 planned compliance and support activities. These included but were not limited to several stakeholder engagement activities to educate and support providers, performing its 2021–22 compliance risk assessment, performing 15 support and 5 targeted compliance visits to providers, and undertaking 3 safe drinking water assessments. The department also mostly achieved its targets for assessing applications for providers' management plans within 3 months and issuing notices within 10 business days.

However, it was only able to meet its target to take compliance action in 34 out of 57 (60 per cent) cases and review incident investigation reports within 10 business days in 76 of the 209 (36 per cent) reports received. Responding to the high number and severity of incidents from natural disasters impacted its ability to meet these targets. The department also had several other targets not met, including updating its guidelines, reviewing its escalation tool, and following up on actions from past safe drinking water assessments.

Natural disasters are a variable the department cannot fully control but are a regular enough occurrence that should be factored into its planning. It is appropriate for the department to prioritise responding to emergent incidents and instances of non-compliance that present immediate or higher risks to water quality, over its planned activities. The need for the department to immediately react to these sorts of issues is not new. It is also likely to continue, given the number of high-risk providers and providers with unmitigated risks in their management plans.

The department has a target to visit each of the 83 providers over a 3-year period. However, it will not achieve this target as it only plans to visit 15 providers per year (covering 45 providers over 3 years). In the last 3 years, the department did not visit or inspect 37 providers, and 6 of these were assessed as high risk in the department’s most recent assessment.

Key activities are not included in the compliance plan

The department’s compliance plan does not include targets for timely review of independent audit reports and annual management plan reports. Councils must give these reports to the department to show their compliance with legislation.

- Independent audits are the key source of external assurance of a council’s compliance with the legislation. These reports include action items and recommendations.

- Annual management plan reports list actions the councils have taken to implement their management plans and act on outcomes from independent audits, water testing results, incidents, and complaints from customers.

Reviewing these reports takes the department some time. For example, depending on the contents of these reports, the department may need to act before it can finalise the review. This can include obtaining more information from the council or taking compliance actions.

Even taking this into account, the department is taking a long time to review them. In 2022–23, the department received 15 audit reports. Based on the department’s data, it took an average of 251 days to finalise the review of 9 reports, and 6 report reviews are still not finalised. In addition, there are 3 out of 5 reviews from independent audits from 2023–24 still to be finalised.

The department also received 83 annual reports in 2022–23. It took an average of 219 days to review 55 reports, and it has not finished its review of the remaining 28 reports. In addition, there are 66 out of 83 reviews of annual reports from 2023–24 still to be finalised.

Improving workforce planning

In June 2023, the department had approximately 16 full-time equivalent staff in its water supply regulation team. Based on the staff it has, it was not able to fully deliver its compliance program. While responding to incidents affects the department’s capacity to perform these activities, incorporating this into its planning considerations will be necessary if it is to maximise its effectiveness.

In 2023, the department started a project to identify the staff resources needed for it to effectively deliver on its legislated responsibilities and its annual compliance program. In June 2024, the water supply regulation staff had increased from 16 to approximately 18 full-time equivalents. Enhancing its workforce planning will also help to address the backlog of reports from independent audits and annual reports.

Recommendation 8 We recommend the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers enhances its workforce planning to ensure it has sufficient resources to deliver its compliance activities, meet the demand for responding to incidents, and review the providers’ audit reports and annual reports in a timely manner. |

Does the department act on non-compliance?

Regulatory actions to address non-compliance should be proportionate to the identified public health risks and should deter future instances of non-compliance. The department has a range of regulatory actions to use at its discretion. These include taking:

- no action, or taking informal action by speaking directly with the provider

- formal, non-statutory action such as sending reminder letters and warning letters

- statutory action such as making requests for information or issuing notices (show cause, compliance, or direction).

The department can also issue enforcement actions, such as penalty infringements, and it can prosecute when warranted.

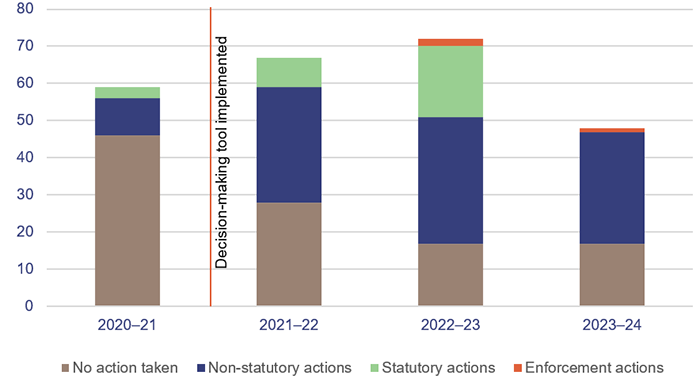

In 2021, the department implemented a decision-making tool to guide its escalation of actions against non-compliant providers. It has since used a greater range of regulatory actions available to it to address non-compliance.

Figure 5C summarises the department’s actions in response to non-compliance between 2020 and 2024.

Compiled by the Queensland Audit Office using data from the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers.

From 2020–21 to 2023–24, the department responded to 246 instances of non-compliance, 90 per cent of which involved small and medium providers. Of these instances, 76 were classified as having the potential for harm (that is, they could impact on the safety of drinking water). For those with a potential for harm, the department:

- took no action for 13 instances

- issued warning letters for 40 instances

- took other statutory and non-statutory actions for 22 instances (including performing investigations or inspections or issuing compliance, direction, show cause, or requests for information notices)

- issued an infringement notice in one instance.

In one case, a small provider supplied untreated water directly to the town’s reservoir due to a power outage that shut down the treatment plant. The water operator was on leave and unable to respond to the outage. The department identified further issues with this provider’s results from its water testing. The provider had 4 instances of non-compliance in one year, yet the department took no formal action in 2 instances and issued warning letters for the other 2 instances.

Since the Water Supply (Safety and Reliability) Act 2008 (the Act) came into effect, the department has issued fines to 4 providers who failed to comply with the conditions of their management plans. While the department has increased the number of actions it has taken since introducing its decision-making tool, it should evaluate if its actions in response to non-compliance are effective at bringing providers into compliance. This should include where it decides to take no action.

Recommendation 9 We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers evaluates its response to non-compliance and assesses the effectiveness of outcomes from its actions. |

Does the department respond well to incidents?

Managing incidents is a key part of providing safe drinking water, such as responding to algae outbreaks or equipment failures. Councils are ultimately responsible for managing and reporting them, but the department plays a key regulatory role in ensuring that councils have responded appropriately and are taking steps to prevent similar incidents.

The department has an effective process for recording and responding to reported incidents. It appropriately escalates, within the department, those incidents that are high risk, and reports those with a risk of public harm directly to the relevant public health unit at Queensland Health. In 2023–24, the department recorded 318 incidents (2022–23: 224).

The department monitors the incidents until the councils resolve them. It logs the incidents in the compliance system and tracks the councils’ actions through incident investigation reports (which the council must submit). In some instances, the department also performed site visits and investigations when it determined further actions were required. While the department’s process for recording and monitoring the incidents is effective, it takes a long time to review the investigation reports submitted by providers. This increases the risk that the department may not be aware if providers have responded appropriately.

The department maintains records about whether each incident resulted in a boil water alert. Some incidents may lead to a report of non-compliance if the council has not acted in accordance with its approved plan for managing drinking water quality.

Does the department effectively monitor and report on water quality?

One of the department’s strategic objectives relates to minimising risks to drinking water and achieving public safety outcomes. However, it does not collect the data it needs to measure this, despite having the regulatory authority to require providers to supply it.

Providers have the primary responsibility to monitor water quality trends and report incidents to the regulator. They supply their testing results to the department in annual reports. These reports summarise the number of tests that exceed a safety or aesthetics limit (characteristics of drinking water specified in the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines).

But the department cannot use the reports to monitor trends or identify potential emerging problems, as it does not require the providers to supply the underlying data. Providers are already collecting this information and requesting it could offer the department insights into whether water quality is improving or not. It could also streamline the process of verifying reporting requirements and give the department enhanced confidence tests were performed, which is a common area of non-compliance.

Recommendation 10 We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers enhances the data it collects on drinking water quality and implements a process to monitor and report on water quality. |

The department’s external reporting needs to be improved

The department reports externally on its performance in its annual compliance report and its annual service delivery statement. Its measures in the annual compliance report could be improved with specific and time-bound targets to drive performance towards goals. For example, the report describes outputs, such as the number of completed compliance inspections, rather than the outcomes of the work and whether they were delivered efficiently and effectively.

The department also reports in service delivery statements on the percentage of providers compliant with regulatory requirements, such as submitting their independent audits and annual reports on time. In 2022–23, the department reported that 98 per cent of providers were compliant.

The department calculates the percentage on a quarterly basis, which complies with the approved methodology. However, providers only submit annual reports once a year and independent audits every 4 years. It means a provider could be counted as compliant 4 times, despite only being due to provide its annual report once.

If the methodology included all types of non-compliance and was calculated annually, the department's service delivery statement would have shown that 59 per cent of providers were fully compliant in 2022–23, instead of the 98 per cent it reported. This type of performance measure would provide a more accurate reflection of the challenges regional and remote providers face with meeting their legislative requirements.

The department’s internal quarterly reports on its regulatory activities allow for adequate monitoring of non-compliant providers and ongoing incidents. It appropriately oversees these until they are resolved.

It also uses these reports to track progress of its planned support and compliance activities.

Recommendation 11 We recommend that the Department of Local Government, Water and Volunteers improves how it measures its performance and reports externally by:

|