Overview

Youth crime is complex and has been a growing public concern in recent years. It can have significant impacts – physical, emotional, psychological, and economical – for victims and the wider community. Most young offenders only commit a small number of offences and are diverted away from the youth justice system. However, a small proportion reoffend and commit serious offences. As the underlying causes of youth crime are multi-faceted, effectively addressing the problem requires a whole-of-system approach.

Tabled 28 June 2024.

Auditor-General's foreword

A personal message

After 7 years and 114 reports to parliament containing 412 recommendations, this is now my last. It has been a great privilege to serve parliament and the Queensland community as your Auditor-General and to lead the Queensland Audit Office (QAO).

The support I have received from QAO and its people – including our audit service providers and contractors, has been outstanding and I thank them all. Together we have worked as OneQAO to provide assurance to parliament and to help it in its role to hold public sector entities to account for better public services. As concluded by the recent 2023 Strategic review of QAO, the office has served parliament and the Queensland community well, and is well placed to face new challenges.

Reducing serious youth crime

My last report could not be about a more complex matter that is impacting the lives of many Queenslanders. It raises recurring themes and issues I have seen over the past 7 years, which are hindering entities’ effectiveness in reducing serious youth crime.

We continue to see that entities find working within a multi-agency operating model inherently challenging. They typically have their own mandates, objectives, and leadership. But when it comes to operating within a ‘system,’ entities are not always collaborating effectively, and often, there is no one entity with overall accountability and authority.

Multiple entities are responsible for various parts of the youth justice system, but no one entity is accountable for its success nor empowered to direct how stakeholders’ resources are used. To use an analogy, all entities are rowing…but no-one is singly responsible for steering an overall integrated response and for holding stakeholders to account. Some of the entity responses to this report further highlight the need for better collaboration.

Impeding entities' progress in reducing serious youth crime, and many aspects of public service delivery, is the impact of machinery of government changes. While such changes are the prerogative of government, the state has seen too many and it greatly impacts momentum in delivering public services. As detailed in this report, over the last 7 years, responsibility for youth justice has moved between departments 5 times.

In Professor Coaldrake’s 2022 report Let the sunshine in: Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector, I paraphrase, but he reflects that machinery of government changes typically occur to agencies servicing more vulnerable community groups. We most recently saw this with the 2023 shifts for youth justice, seniors, and disability services.

As Professor Coaldrake opined, restructuring agencies is not a substitute for strategy, and it does not guarantee improved performance.

Many of my reports underline the disruption caused by machinery of government changes, which map back to the recommendations in my report State entities 2021 (Report 14: 2021–22). We recommended the Department of the Premier and Cabinet and Queensland Treasury advise the incoming/returning government on the risks of restructures and draw on past lessons. We recommended they require departments to report on the community and service delivery benefits, and the cost of changes – and provide guidance on how to do so. These recommendations have not yet been fully implemented.

I acknowledge that addressing the challenge of youth crime is not a simple fix, nor unique to Queensland. It is a multi-faceted matter that spans some of the largest areas of public services such as the health and education systems, housing, and the role of families.

The Auditor-General has a broad mandate, however must not question the merits of government policy objectives. This means we cannot make recommendations on the specific direction or strategies government should take. The findings and conclusions in this report relate to whether entities are implementing the government’s policies efficiently, effectively and economically, in line with its policy objectives.

I hope to see the Queensland Government’s timely attention to the long-standing, inherent problems I mention here, and entities’ action on my findings and recommendations.

Brendan Worrall,

Auditor-General.

Report summary

Youth crime is a complex problem that has touched the lives of many Queenslanders. The underlying causes of youth crime are multi‑faceted. Many young offenders have poor health, including mental health issues and behavioural disorders; many are disengaged from education and employment. A whole-of-system approach is needed to address this complex problem.

Note: The number of serious repeat offenders is based on the Department of Youth Justice’s serious repeat offender index.

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

Most young offenders only commit a small number of offences and are diverted away from Queensland’s youth justice system (the system). However, a small proportion reoffend and commit serious offences.

In this report, we focus on these serious repeat offenders, who are a threat to the safety of our communities.

System leadership has improved, but needs to be more effective

Leadership has improved in recent years, but further work is required to make it more effective. Constant government restructures (5 over the past 7 years), legislative changes, and instability in leadership positions within entities have hindered efforts to reduce crime by serious repeat offenders.

The government has improved oversight and coordination by establishing system-wide governance committees, including the Community Safety Cabinet Committee, the Youth Justice Taskforce Senior Officers Reference Group (the taskforce), and multi-agency collaborative panels. The taskforce and panels have been a positive step, providing an effective platform for entities to coordinate and prioritise their responses. However, their effectiveness is diminished by a high proxy attendance and, at times, a lack of action to address key challenges across the system, some of which are long standing. These challenges include the lack of capacity in detention centres and the over‑representation of First Nations youth in the system. While these committees provide oversight and coordination, there is a need to define who has overall responsibility and accountability for the youth justice system. The Department of Youth Justice (the department) leads the government’s response to youth justice, but as a stand-alone entity it does not have authority to make decisions across the system.

Better system-wide analysis is required to inform investment

The government has invested heavily in a range of rehabilitation, support, and community-based programs to address crime by young offenders. This investment would be strengthened by implementing stronger planning and analysis at both the system and entity levels. Entities need to work together at a system level to ensure there is adequate investment in services that protect children from those factors that put children at risk of offending. These services may include community, health, housing, education, and others. Similarly, the department needs to strengthen its analysis to ensure it is investing in the right programs, at the right locations.

The department, who is responsible for funding entities that deliver programs that rehabilitate young offenders, could not demonstrate that it was regularly testing the market. This increases the risk that its investments do not achieve value for money or meet the needs of young offenders. Contract management practices also need to be strengthened to support better outcomes for young offenders.

Entities need to better implement their new youth justice strategy

The government had a comprehensive state strategy, Working Together Changing the Story: Youth Justice Strategy 2019–2023, which expired at the end of 2023. However, it did not implement it effectively. This included only developing and implementing an action plan for part of the strategy, not for the full period. The department has drafted its new youth justice strategy and needs to address these gaps when implementing its new strategy. The Queensland Police Service (QPS) needs to finalise its own youth justice strategy and ensure it aligns with the state’s strategy.

Greater system-wide evaluation is needed to determine if the government’s actions are reducing crime by serious repeat offenders and improving community safety. The Department of the Premier and Cabinet’s new system evaluation responsibilities aim to address this gap.

More can be done to monitor and rehabilitate serious repeat offenders

Entities undertake a range of activities to address youth crime in high-risk areas and provide better support to communities. This includes the Queensland Government’s youth co‑responder teams, which fill an important gap in services and ensure 24/7 support to young people across the state. While QPS is increasing its police presence in communities where there are high rates of youth crime, it can strengthen its processes for checking that young offenders comply with their bail conditions.

QPS and the department do not have a consistent way of identifying those young offenders with the highest risk of reoffending. These different approaches are resulting in entities identifying different cohorts. This increases the risk that some high-risk offenders may miss out on getting the rehabilitation or case management they need to address their offending behaviour.

The department has designed a suite of programs to rehabilitate young offenders, including serious repeat offenders. These are based on, or informed by, evidence and better practice. However, it is difficult to determine their effectiveness due to poor data capture and a lack of independent evaluation and monitoring against outcomes.

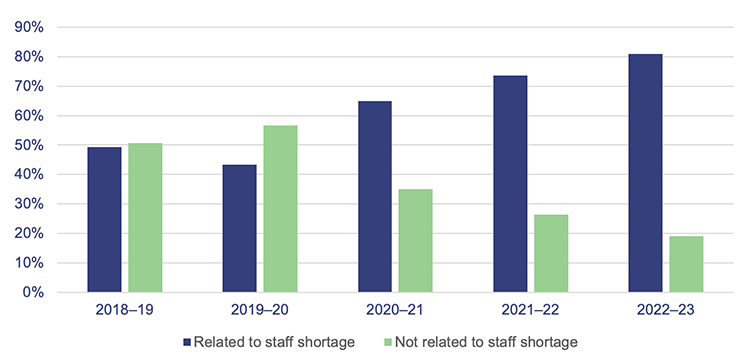

The young offenders who are in detention are not always getting the rehabilitation or education they need to address their offending behaviour. This is partly due to Queensland’s youth detention centres often being locked down because of staff shortages, safety incidents, and other factors. Cleveland Youth Detention Centre had the highest staff shortages when compared to the other centres. The department has implemented a range of strategies to address these staff shortages at Cleveland Youth Detention Centre, including using a greater variety of platforms to attract applicants. While it has increased staffing levels, additional staff are still required for the centre to operate effectively and avoid lockdowns.

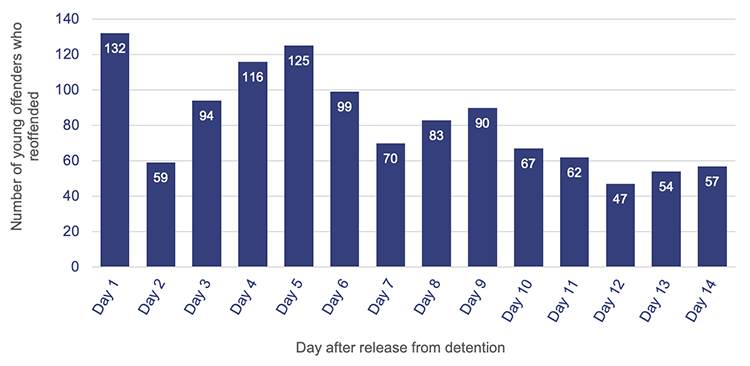

The department needs to better manage a young offender’s transition from detention to the community

More can be done to support young offenders leaving detention. Leaving detention is a particularly susceptible time for serious repeat offenders. While the department provides case management support to young offenders before and after they leave detention, its primary approach to managing their transition from detention back into the community is its 72-hour plans. These plans are not based on evidence and the department could not explain the rationale for only planning for the first 72 hours after a young offender’s release. We found 72 hours may not be sufficient, and a transition plan covering a longer period is needed. The department did not always prepare a 72-hour plan for serious repeat offenders leaving detention, and the quality and consistency of them varied significantly.

Our audit scope

Our audit focused on the work entities are doing to address crime by high-risk and serious repeat offenders, given the impact they have on our communities. We assessed whether youth justice strategies and programs are effective in reducing crime by serious repeat offenders and improving community safety. We acknowledge the significant work entities do to identify at-risk young people and intervene early in their lives. This work, in areas such as education, health, and housing, is critical to deter young people from entering the system. This report does not assess or conclude specifically on these areas.

1. Audit conclusions

While the government has acted to address youth crime in Queensland, more needs to be done to reduce crime by serious repeat offenders. Since 2015, the government has undertaken significant reform, including changing laws, implementing a comprehensive state strategy, and increasing investment in youth justice services. However, strategies to date could be more effective in addressing this complex problem. Contributing to this is a need for more consistent leadership across the youth justice system (the system). The number of serious repeat offenders continues to increase, First Nations young offenders continue to be over-represented, and community confidence has diminished.

Addressing serious youth crime is a complex challenge, particularly given the drivers of youth crime are multi-faceted. A more comprehensive systems approach is necessary to ensure entities work together to address these drivers. The government must continue to build stronger collaboration, leadership, and accountability across the system.

Managing Queensland’s youth justice system

While progress was made under the previous strategy, it was not as effective as it could be due to inadequate planning to support its implementation. A lack of key performance indicators and system-wide monitoring and evaluation made it difficult to conclude whether the strategy was effective.

The Department of Youth Justice (the department) has drafted a new strategy and intends to publish it in the second half of 2024. It needs to better implement the strategy and address gaps in monitoring and reporting. Key to its success will be improving leadership, coordination, and accountability across the system.

The government has established appropriate (in design) governance committees to provide system oversight and coordination. However, their effectiveness has been hindered by a high proxy attendance, inconsistent approaches, and, in some cases, a lack of action. Constant government restructures (referred to as machinery of government changes) and instability in leadership positions within entities have also been counter-productive. Within these governance committees there is no clear decision-maker who can be held accountable for the committee’s performance. Government needs to clarify who has the authority to make decisions across the system.

Rehabilitation and community safety

Both QPS and the department have a clear focus on increasing community safety through their strategies and programs. This includes increasing police presence in high-risk areas and establishing new detention and remand facilities. While this may provide short-term relief, entities need to complement this work with longer-term solutions, such as the delivery of rehabilitation and other support programs.

It is unclear whether entities are investing in the right programs in the right locations to reduce reoffending. The governance committees responsible for leading the system do not undertake system‑wide investment analysis to inform funding decisions, nor does the department. The Department of the Premier and Cabinet intends to do this investment analysis as part of its new system evaluation responsibilities. For those investments made, entities need to strengthen procurement and contract management practices to ensure the services represent value for money and address the needs of young offenders.

The department has a suite of programs it delivers to rehabilitate young offenders, including serious repeat offenders, that are based on, or informed by, evidence and better practice. However, poor data capture hinders the department in determining their effectiveness. The department has taken positive steps to improve its data collection and implement a framework to better measure the outcomes of its actions. It now needs to begin monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of its programs against the outcomes framework.

Serious repeat offenders in detention are not always getting the rehabilitation and education they need. This is because some of the department’s youth detention centres are often locked down due to staff shortages, safety incidents, and other factors, such as medical emergencies. In addition to this, young offenders leaving detention in Queensland need better support. While the department plans for the first 72 hours and provides case management support during and after this period, it can better plan and support young offenders during this transition.

2. Recommendations

| Managing Queensland’s youth justice system |

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet continues to work with key system stakeholders to: 1. ensure more effective coordination, integration, and delivery of youth justice-related initiatives, including facilitating whole-of-government investment and implementation where appropriate. |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice and the Queensland Police Service, in collaboration with other relevant stakeholders: 2. strengthen their leadership and governance of the youth justice system (the system). This should include

|

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders: 3. reviews, updates, and implements its new youth justice strategy. The strategy should

|

We recommend that the Queensland Police Service: 4. finalises its youth justice strategy, ensuring it includes measurable objectives and aligns to the state strategy. |

We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, in collaboration with the Department of Youth Justice: 5. finalises its system-wide monitoring and evaluation framework and commences evaluation of 2023 youth justice reforms. This should include

|

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice: 6. formalises and executes a plan for measuring the effectiveness of programs using its outcomes framework. |

| Investment in youth justice services |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice: 7. strengthens its investment and procurement practices to ensure that all investment decisions are based on sound market analysis, with the rationale for decisions clearly documented in line with evidence. This should include

|

| Rehabilitation and community safety |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice and the Queensland Police Service, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders and governance committees: 8. agree on a uniform, evidence-based approach to identifying those young offenders with the highest risk of reoffending and ensure this information is shared with relevant stakeholders across the system. |

We recommend that the Queensland Police Service: 9. monitors bail checks for serious repeat offenders to ensure timely and appropriate action. |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice: 10. improves and standardises its processes and systems for collecting and recording data about its core rehabilitation programs and support services. This should include providing appropriate training and guidance to staff to ensure data is collected as required. |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice: 11. continues to implement plans to address staff shortages at detention centres, including considering alternative methods to rehabilitate young offenders while centres are in lockdown. |

We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice: 12. ensures there is effective and sustained support to young offenders transitioning from detention into the community. This should include

|

Reference to comments

In accordance with s. 64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

3. Youth crime in Queensland

Offending by 10–17 year olds (the legislated age for criminal offences by young people) has been an increasing community concern in Queensland in recent years. Youth crime, as with all forms of crime, has significant impacts, both for the victims of the crime and for the broader community. These impacts can be physical, emotional, psychological, and economical.

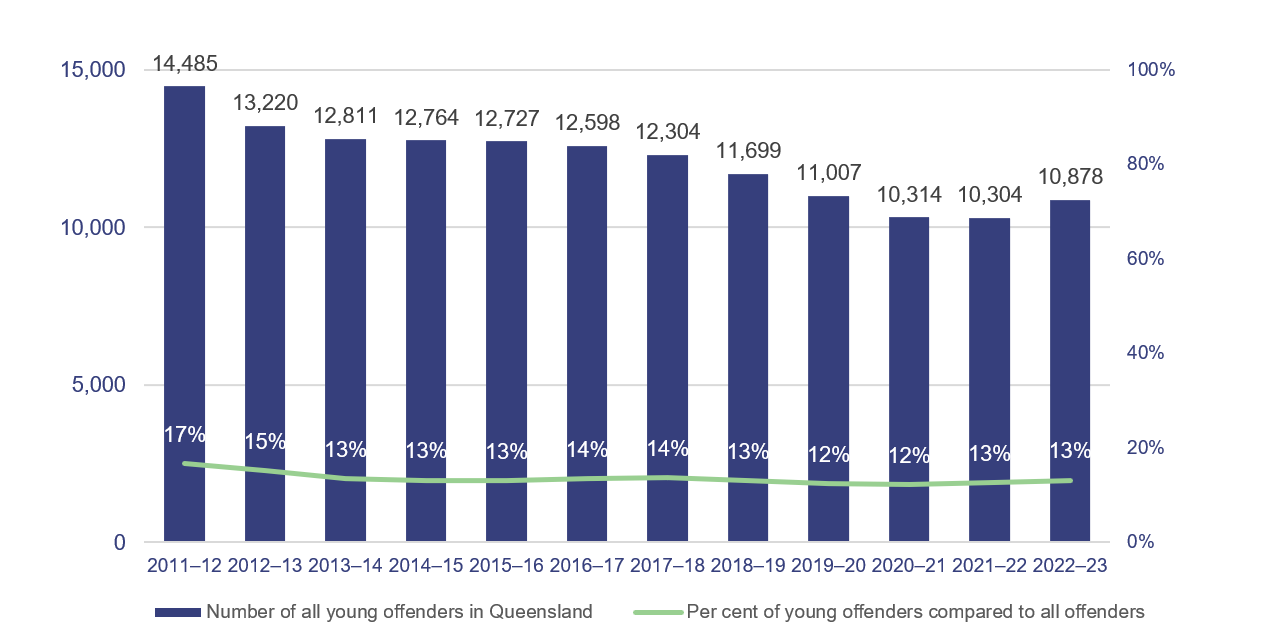

The number of young people charged with an offence in Queensland has steadily decreased since 2011 – from 14,485 in 2011–12 to 10,304 in 2021–22. However, in 2022–23, the number of young offenders charged increased by 6 per cent, to 10,878. This increase was at a greater rate than population growth, which also increased over this time. There are many factors that can influence crime trends, including changes in policing strategies, new youth justice laws, and societal pressures. As such, trends may not be solely attributable to the behaviour of young offenders.

Youth crime accounts for only a small percentage of overall crime in Queensland. The percentage has decreased from 17 per cent of overall crime in 2011–12 to 13 per cent in 2022–23.

Figure 3A shows the number of young people charged with an offence or cautioned from 2011–12 to 2022–23. It also shows the percentage of young people charged with an offence compared to all offenders charged during this period. The graph below does not reflect trends in the severity of crimes.

Note: This graph shows the number of young offenders that the Queensland Police Service has charged for an offence and those it has cautioned.

Queensland Audit Office using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Serious repeat offenders

Most young people who are charged by police with offences do not go on to commit further offences. However, a small number continue to offend and commit serious crimes. In this report, we refer to these young offenders as serious repeat offenders.

The Department of Youth Justice (the department) defines a young offender as a serious repeat offender if they commit a disproportionally large number of serious offences, including offences such as assault, attempted robbery, or unauthorised use of a motor vehicle.

It uses an index to identify serious repeat offenders. The Serious Repeat Offender Index (SROI) identifies serious repeat offenders based on a range of factors, including number of charges over the last 2 years, severity of offences, time spent in custody, and the young offender’s age. Most serious repeat offenders have been charged with more than 70 offences.

These serious repeat offenders are responsible for most youth crime and pose a risk to the community. In 2022–23, serious repeat offenders committed 55 per cent of all proven youth crime.

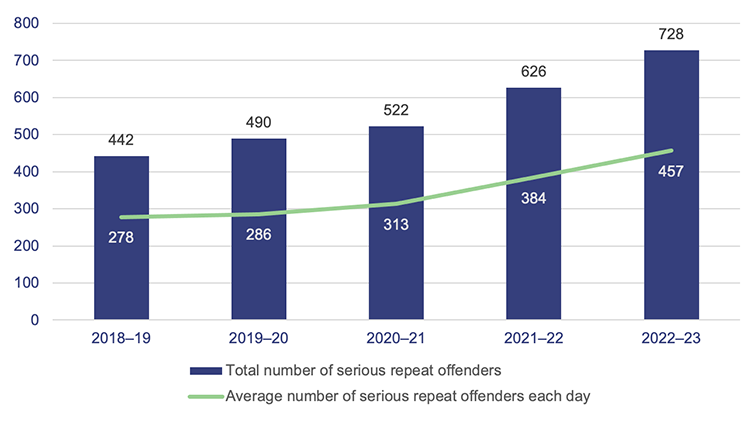

Since 2018–19, the number of serious repeat offenders reported by the Department of Youth Justice has increased by 65 per cent from 442 in 2018–19 to 728 in 2022–23. Figure 3B shows the number of serious repeat offenders between 2018–19 and 2022–23, including the total and average daily number by financial year.

Notes: This graph is based on the number of offenders that the Department of Youth Justice identifies as serious repeat offenders. It uses the Serious Repeat Offender Index to identify serious repeat offenders based on their prior offending over the last 2 years, severity of offences, time spent in custody, and the young offender’s age.

Queensland Audit Office using data provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

Young people in Queensland were most commonly charged with theft, break and enter, drug offences, and use of stolen vehicles between 2018–19 to 2022–23.

First Nations youth make up the majority of serious repeat offenders in Queensland, accounting for 69 per cent of all serious repeat young offenders.

Identifying and addressing the causes of youth crime

Research indicates that many young offenders experience complex issues within their family, including neglect, domestic and family violence, and drug and alcohol abuse.

Many have poor health, including mental health issues and behavioural disorders; many are disengaged from education and employment. Most, if not all, of these issues are relevant to First Nations youth. Some, such as limited access to education, healthcare, and housing, are disproportionately experienced by First Nations families and young people. The over-representation of First Nations youth is not unique to Queensland; it is present throughout Australia and documented as a symptom of social and economic disadvantage.

Anecdotal evidence suggests social media can also be a driver of youth crime, where young people seek notoriety by posting or livestreaming their crimes on various platforms.

Addressing the drivers of offending behaviour is critical. It requires evidence-based strategies and programs that target the specific needs of the young offender and their individual risks.

Strategies and programs need to be delivered at the right intensity and frequency. These strategies and programs need to continue if the young person spends time in detention and when they transition back into the community.

Who is responsible for addressing youth crime?

Queensland’s youth justice system (the system) involves many stakeholders, including government, non‑government organisations, and communities. Some organisations focus on early intervention for young people at risk of offending, while other organisations deliver programs designed to keep children out of court and custody, and reduce reoffending.

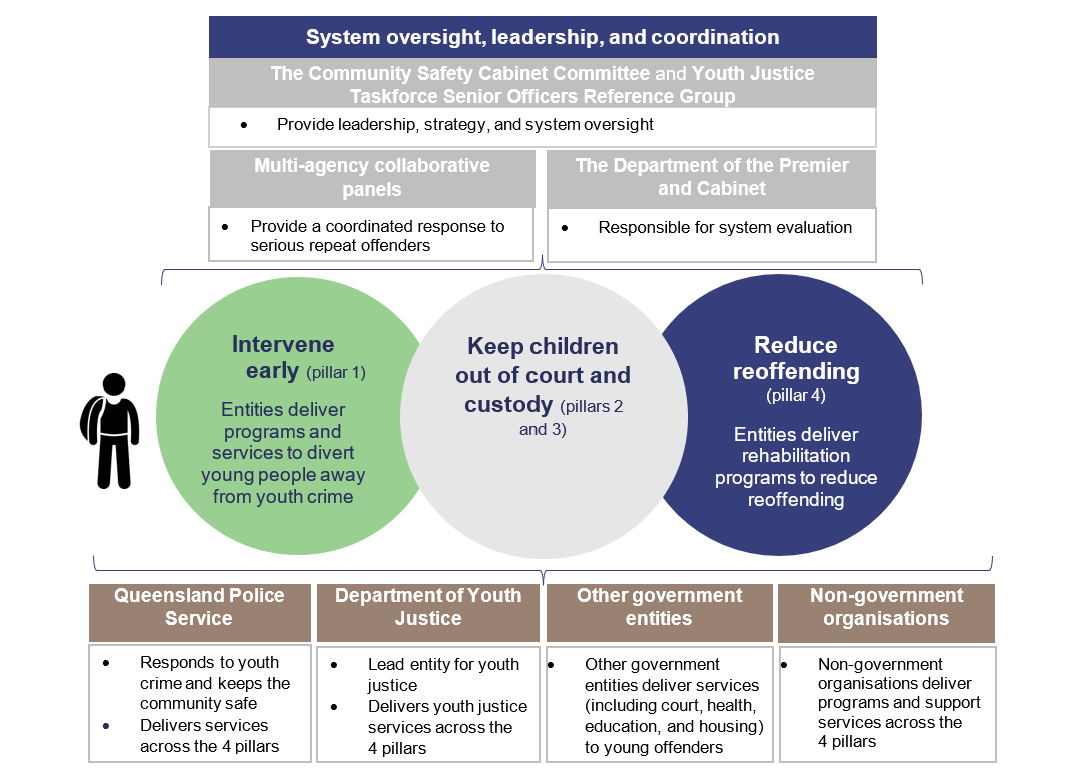

Since 2015, the Queensland Government has undertaken significant reform to change the way entities respond to youth crime and make communities safer. This includes implementing the Working Together Changing the Story: Youth Justice Strategy 2019–2023 (the strategy), which provides a framework to address youth crime in Queensland. The strategy is underpinned by a goal of community safety and confidence and includes 4 key pillars: intervene early (pillar 1), keep children out of court (pillar 2) and custody (pillar 3), and reduce reoffending (pillar 4). Figure 3C shows the stakeholders involved in the system and where they deliver services across the 4 pillars.

Note: Other government entities include Department of Education; Queensland Health; Queensland Corrective Services; Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works; Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services; Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities and the Arts; Department of Justice and Attorney-General, responsible for administering the Childrens Court of Queensland; Queensland Family and Child Commission; Queensland Ombudsman.

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

Youth Justice Act 1992

The Youth Justice Act 1992 is the key piece of legislation governing youth crime in Queensland. It sets out the youth justice principles, which include:

- ensuring the community is protected from offences and, in particular, from serious repeat offenders

- upholding the rights of children, keeping them safe, and promoting their physical and mental wellbeing.

Who we audited

We audited those entities that primarily deliver or fund programs and services for serious repeat offenders under pillar 4. They include the Department of Youth Justice, the Queensland Police Service, and the Department of Justice and Attorney-General.

We also audited the Department of the Premier and Cabinet because a recent initiative has made it responsible for system-wide evaluation.

The Department of Youth Justice is the lead entity responsible for youth justice in Queensland. It is responsible for a range of youth justice services, including:

- assessing the needs and risks of young offenders and providing case management support

- delivering rehabilitation programs and other support services

- leading the state strategy and prioritising funding in youth justice service providers

- detaining high-risk offenders and managing Queensland’s youth detention centres.

The Queensland Police Service is responsible for keeping communities safe and preventing and responding to youth crime. Its responsibilities include issuing cautions to deter young people from entering the system and charging young offenders who have committed an offence. It also delivers a range of youth crime programs and checks on young offenders who have been granted bail. A young person may be granted bail (released from custody but needing to return to court at a set date) while they are waiting for their charges to be dealt with.

The Department of Justice and Attorney‑General is responsible for the administration of Queensland courts. This includes the Childrens Court (Magistrates Court) and the Childrens Court of Queensland (District Court). In this report, we refer to these collectively as the Childrens Court. It is also responsible for justice policy and reform.

Other entities, including government and non-government organisations, play a critical role in delivering services to young offenders and their families.

What we audited

In this audit, we assessed whether youth justice strategies and programs are effective in reducing crime by serious repeat offenders and improving community safety.

We examined the design and implementation of the in-scope entities’ strategies and programs, and assessed how they measure and report on their effectiveness. We also assessed the leadership, strategy, coordination, and funding across the youth justice system. In many cases, these are interconnected.

4. Managing Queensland’s youth justice system

Effective leadership and a clear strategy are vital to manage Queensland’s youth justice system (the system). Having the right programs available in the right locations is paramount.

To be effective, entities need to work together, and programs must address the underlying causes of youth crime. Entities need to monitor and measure the outcomes of their activities to determine what is working, and what they can improve.

This chapter examines whether entities have effective strategies and leadership to manage the system and reduce crime by serious repeat offenders. It also examines how entities coordinate their activities and measure their effectiveness.

Is leadership and coordination effective?

More effective and stable leadership is needed to address key challenges across the system.

In recent years, the Queensland Government’s leadership of youth justice has lacked stability. Over the past 7 years, responsibility for youth justice has moved between departments 5 times. This constant change over an extended period is disruptive, and can cause inconsistent messaging, direction, and uncertainty. In our recent report Implementing machinery of government changes (Report 17: 2022–23), we highlighted that government restructures take considerable time and effort and divert the focus of public servants to the restructure.

In addition, there has been instability in leadership positions within entities. For example, the Queensland Police Service (QPS) has had 3 different assistant commissioners responsible for youth justice over 3 years.

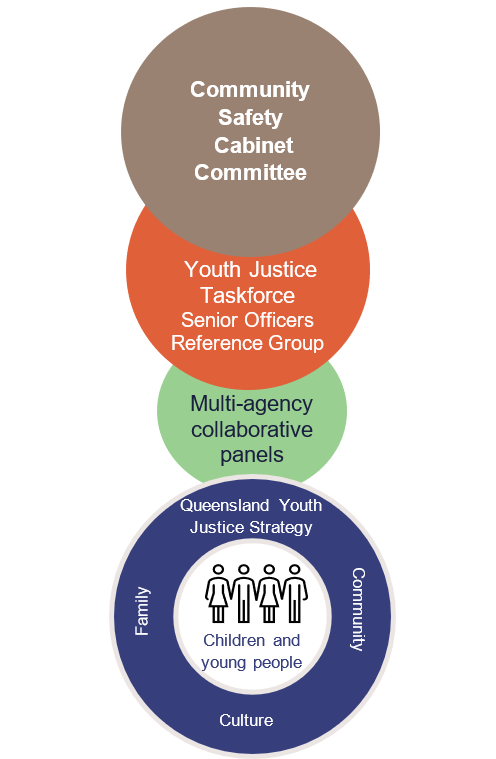

Despite the instability, the government has established cross-agency committees to help lead the system. Figure 4A captures the key governance committees providing leadership and coordination across the youth justice system.

Queensland Audit Office using information from the Department of Youth Justice.

The government’s committees are a positive step to provide strategic leadership, however their effectiveness is diminished by a high proxy attendance and, at times, a lack of action.

The Community Safety Cabinet Committee (formally the Youth Justice Cabinet Committee) was established in 2021. The committee meets quarterly and includes ministers from relevant agencies. It is responsible for:

- ensuring cohesive whole-of-government responses effectively target serious repeat offenders

- reducing the over-representation of First Nations young people at all stages of the system

- restoring community confidence in youth justice responses in Queensland.

The Youth Justice Taskforce Senior Officers Reference Group (the taskforce) was established in February 2021. The taskforce is responsible for providing whole-of-government strategic leadership and advice to inform the government’s responses to young offenders.

This includes:

- identifying risks, blockages, and challenges, and developing appropriate strategies

- ensuring timely, efficient, and effective completion of commitments by members.

The taskforce includes members from all key entities and is chaired by QPS. It has appropriate terms of reference.

Since its creation, the taskforce has met at least monthly. However, its value has been diminished by the poor attendance of members at meetings. From a sample of 9 meetings over 3 years, we found that members only attended 49 per cent of the time. Instead, entities sent a proxy representative who, in some cases, may not have had the appropriate authority to drive system change.

We also found that, although the taskforce identified and discussed key challenges impacting Queensland’s youth justice system, it has not always taken the necessary action to address those challenges. Some of those challenges include the pressure on Queensland’s youth justice system and the over‑representation of First Nations youth in the system. For example, the taskforce has not developed or implemented a strategy to address the over-representation of First Nations young offenders, despite discussing the issue at 3 of the 9 meetings we sampled. We discuss actions taken to address the over-representation of First Nations youth further in this chapter.

While the government has established appropriate governance committees to lead the system, it is not clear who has authority within these committees to make decisions across the system. The Department of Youth Justice (the department) has a lead role across the system, but as an individual entity does not have the authority to make decisions at a system level. Given the high number of stakeholders involved in the system, this creates challenges in effectively delivering initiatives. The Department of the Premier and Cabinet, which is responsible for whole-of-government policy and evaluating the youth justice system, is well positioned to address this challenge to ensure more effective collaboration across the system.

Recommendation 1 We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet continues to work with key system stakeholders to ensure more effective coordination, integration, and delivery of youth justice-related initiatives, including facilitating whole-of-government investment and implementation where appropriate. |

Queensland’s youth justice system is under pressure

Since 2018–19, the number of serious repeat offenders increased by 65 per cent from 442 to 728 in 2022–23. In addition, the number of young people charged with an offence in Queensland increased from 10,304 in 2021–22 to 10,878 in 2022–23, despite steadily decreasing in prior years. This adds pressure on police resources, watch houses, youth detention centres, courts, and social services. As a result, in 2022–23 all 3 of Queensland’s youth detention centres were operating over their safe capacity by an average of 23 young offenders each day. Others were detained in police watch houses, designed to hold adults. The government has taken some actions to address these pressures:

- In March 2023, the Department of Justice and Attorney-General implemented the Fast Track Sentencing Pilot to identify the causes of court delays, reduce the number of young offenders on remand, and reduce the time taken to finalise court cases and reduce the length of time young offenders spend on remand. The department reports that the median time to finalise cases for young offenders has improved at 2 (Cairns and Townsville) of the 4 court locations. The pilot will finish in late 2024.

- In May 2023, the government committed to build 2 new youth detention centres (Woodford and Cairns). These centres are expected to be operational in 2026–27. In addition, the government is converting the Caboolture Watch House to be a specialist watch house for children.

- In October 2023, the government announced it would build a youth remand centre in Wacol, with accommodation for 76 young offenders. The centre will give young offenders access to exercise areas, education, medical care, and therapeutic programs. It is expected to be operational in late 2024.

While these actions will, to some extent, alleviate pressure on detention centres, more effective leadership and coordination are needed to address the pressure on the youth justice system and the drivers of youth crime.

Multi-agency collaborative panels enable good coordination and collaboration across the youth justice system

In 2021, the Queensland Government established multi-agency collaborative panels (MACPs) to bring together relevant entities and non-government service providers to assess and respond to the needs of serious repeat offenders. MACPs fulfil an important need by enabling entities to collaborate and providing a coordinated response to serious repeat offenders.

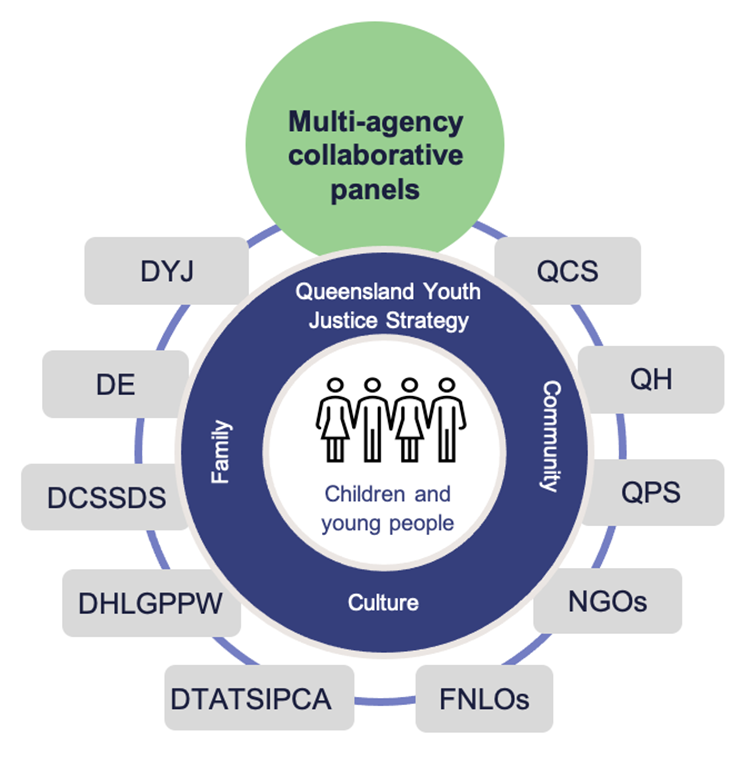

Figure 4B shows the key entities that are commonly members of MACPs.

Note: DYJ – Department of Youth Justice; DE – Department of Education; DCSSDS – Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services; DHLGPPW – Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works; DTATSIPCA – Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities and the Arts; FNLOs – First Nations-led organisations; NGOs – Non-government organisations; QPS – Queensland Police Service; QH – Queensland Health; QCS – Queensland Corrective Services.

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

Since 2021, MACPs have operated informally across the state. In March 2023, the Queensland Government amended the Youth Justice Act 1992 to formally establish MACPs. There are now 19 MACPs across the state. These are chaired by the Department of Youth Justice (the department) and have terms of reference.

MACP delivery needs to improve to maximise effectiveness

While MACPs provide an effective platform for entities to coordinate and prioritise their responses, more can be done to maximise their effectiveness and impact on serious repeat offenders.

To be effective, MACPs need the right members with the right authority, who attend meetings regularly. Our audit shows that this is not happening. For example, none of the 19 MACPs had a representative with appropriate authority from each entity on their membership. Six of the 19 MACPs had no representative from the Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities and the Arts. We reviewed a sample of minutes from 26 MACP meetings across Queensland in 2023. All 26 meetings had at least one absent member or proxy attend, who may not have had the appropriate authority to make decisions. For MACPs to be successful, there needs to be a stronger commitment from entities and members.

MACPs operate inconsistently across the state and, in some cases, this diminishes the value they could add. Some take a strategic and case-management focus. Their agendas include discussions about system issues, youth crime trends, and individual serious repeat offenders. Other MACPs focus solely on individual serious repeat offenders. MACPs should do both. They are well placed to identify and implement strategies to address systemic barriers impacting service delivery.

Actions from MACPs were not always captured and followed up. Some panels documented actions and assigned owners. However, this was not the case for all MACPs we reviewed. Documenting actions is critical in driving the desired outcomes from these meetings. We also heard that processes for escalating issues and identifying the right person to raise issues with is not always clear. We found 9 meetings where system barriers were noted but not escalated. The department is aware of these inconsistencies and recently released a revised mandatory terms of reference to provide further guidance.

More work needs to be done to assess the effectiveness of MACPs. While MACPs provide an effective platform, they are resource intensive. Most MACPs meet at least once a month and have a minimum of 8 entity representatives at meetings. The department has commenced some early data collection to inform MACP effectiveness.

Data and information sharing across the system is improving

In 2019, the government implemented reforms to improve the sharing of data and information between entities. This enabled better system-wide collaboration to support analysis and solutions relevant to serious repeat offenders. Entities advised us that, prior to these reforms, they experienced challenges in sharing data.

In July 2023, the department developed the MACP data dashboard, which allows department staff involved in MACPs to monitor serious repeat offenders (age, gender, location) and their needs (for example, education or housing needs). This dashboard helps the department to better understand and address the highest risks in areas and implement the programs and services needed to support serious repeat offender cohorts throughout Queensland. While MACP members and key government stakeholders do not have direct access to the dashboard, it can be shared at the discretion of the department.

We heard from entities that, while improvements have been made, data and information sharing remains a challenge. The government needs to continue with these reforms to support effective collaboration.

Recommendation 2 We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice and the Queensland Police Service, in collaboration with and other relevant stakeholders, strengthen their leadership and governance of the youth justice system (the system). This should include:

|

Queensland had a well-developed youth justice strategy but lacked sufficient action plans

The state’s strategy Working Together Changing the Story: Youth Justice Strategy 2019–2023 (the state strategy) provided an effective framework to address youth crime in Queensland, including crime committed by serious repeat offenders. The department developed the state strategy based on research and extensive consultation with stakeholders.

The strategy clearly outlined key focus areas, including:

- reducing offending by delivering prevention and early intervention programs

- reducing reoffending and the use of remand in custody

- delivering more cost-effective, community-based options.

Lack of action plans to implement the state strategy effectively

Since 2019, the department, with support from other entities, has implemented a range of initiatives to reduce reoffending. Much of this was informed by its Youth Justice Strategy Action Plan 2019–2021, including:

- implementing a framework to assess the needs of each serious repeat offender, and the risk to their own personal safety and the community

- establishing multi-agency teams to assess and address the factors that contribute to offending behaviour

- expanding rehabilitaton programs.

The department developed a draft action plan for the final period of the strategy from 2021–2023, but failed to implement it. During this time, the department continued to take action to address youth crime. However, without a clear action plan, the department increased the risk that the decisions and actions of entities were not as effective as they could be or did not align with the strategy. The lack of an action plan also limited the department’s ability to monitor the strategy’s progress and implementation.

Queensland needs a better strategy to help First Nations serious repeat offenders

In 2022–23, First Nations youth made up 69 per cent of the serious repeat young offenders in Queensland despite only representing 9 per cent of 10–17 year olds according to 2021 census data. The over-representation of First Nations youth in Queensland’s youth justice system is a significant and long‑term issue.

The state strategy highlights the high numbers of First Nations young offenders. It included 10 actions to better support First Nations youth, including improving cultural capability across government agencies and increasing investment in First Nations service providers. Eight of these actions were the responsibility of the department and 2 of the former Department of Child Safety, Youth and Women.

Some actions lacked sufficient detail. For example, one action was for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Family Led Decision Making Processes to increase cultural authority in the youth justice system. But the action provided no further detail about the level of increase the government was aiming for, or the outcomes it was seeking.

The government reported implementing all 10 actions. In some instances, the government’s response did not address the action. For example, an action addressed to the department was:

'monitoring and evaluation for the Youth Justice Strategy will include goals to reduce the rates of over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in the youth justice system.'

The department reported monitoring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people in the youth justice system and investing in initiatives, but never set goals to reduce the rates of over-representation.

Actions to date have done little to curb the growing numbers of First Nations youth who become serious repeat offenders.

The department has also taken additional steps to improve how it supports First Nations young offenders. These include:

- establishing a First Nations Action Board and having dedicated cultural support officers

- increasing investment in First Nations-led organisations

- designing and delivering programs tailored to First Nations young people, such as On Country. The On Country program aims to better connect First Nations youth to their culture through activities, mentoring, and camps.

More action is required to address this long-standing issue. A whole-of-system approach is needed.

In 2016, the department established the First Nations Action Board (the board). It provides advice to the department to help ensure the decisions it makes are culturally appropriate and beneficial for First Nations young people. While the board discusses priority issues, it has provided limited advice and is not adding the value it could. It provides advice to the director of the cultural capability unit but does not report to the department’s executive leadership team or the system governance committees, and this limits its influence. The board’s roles and responsibilities are not clearly defined in its terms of reference.

The department has limited First Nations staff available to support the cultural needs of First Nations young offenders in some areas across the state. For example, in Mount Isa, 98 per cent (72) of young offenders identify as First Nations, but the service centre only has one staff member who identifies as First Nations and who can provide cultural support and rehabilitation. The department has invested in a number of First Nations-led organisations across the state, but currently does not have one in Mount Isa. We acknowledge there are shortages in Queensland of First Nations staff across multiple industries and government. However, more needs to be done to build capacity across government and non-government organisations to better support First Nations young offenders.

The department is doing more to build its cultural capability. This includes delivering cultural awareness training to its staff across the state. The department reported that 1,476 staff completed cultural awareness training between 2020 and 2023, despite it not being mandatory. The department also has a cultural capability unit that provides input into the design and delivery of rehabilitation programs to help ensure they are culturally appropriate. The unit only provides ad hoc advice and could be engaged in a more formal way.

Recommendation 3 We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders, reviews, updates, and implements its new youth justice strategy. The strategy should:

|

QPS needs to finalise its youth justice strategy

Individual entities need to understand their role in the broader system. They also need to ensure their individual activities and strategies align to the state’s overall youth justice strategy. This is particularly important for QPS, given its policing strategy has a significant impact on the system.

QPS had a youth crime strategy from 2019–2023, that broadly aligned to the state strategy. However, it lacked clarity about its objectives and desired outcomes. It has developed a new draft youth justice strategy and supporting action plans. It aims to finalise the draft strategy in June 2024 and begin implementation.

QPS’s new strategy sets out its strategic priorities, including its new responsibilities for preventing youth crime, which came into effect in May 2023. QPS needs to ensure its draft strategy aligns with the new state strategy. This new role will require a different approach from its traditional policing focus. QPS will need to address a cultural shift needed among frontline officers, from responding to youth crime to preventing it. It will also need to invest more up-front in youth crime prevention initiatives and early intervention activities.

Recommendation 4 We recommend that the Queensland Police Service finalises its youth justice strategy, ensuring it includes measurable objectives and aligns to the state strategy. |

Are entities measuring and reporting outcomes across the system?

Entities are not regularly monitoring and reporting the system’s performance. They are lacking appropriate key performance indicators at a system level to enable this. This makes it difficult to determine how effective the government’s actions have been.

More transparent reporting will provide clarity about whether youth crime across the state is reducing, and may help to address growing concerns in both the media and community.

The department assessed progress against the first half of the 2019–2023 strategy, but not for the full period. While the strategy outlined key focus areas and outcomes, it only included one key performance indictor to measure progress against: to reduce reoffending by 5 per cent. Reoffending has increased from 64 per cent in 2018–19 to 69 per cent in 2021–22. Reoffending trends are measured 12 months after a young offender is found guilty of a crime. As such, reoffending data for 2022–23 is not yet available. Consistent policy and legislative changes have also created challenges for the department in evaluating the overall strategy.

Many of the programs in the strategy focus on prevention. Measuring programs that aim to prevent young people from reoffending can be challenging due to the complex nature of youth crime. It can be difficult to isolate and understand the impact and outcome of a specific program on a young offender’s behaviour.

Work in progress In late 2023, the government established a system-wide evaluation team within the Department of the Premier and Cabinet. This team is developing a monitoring and evaluation framework that will examine multi-agency initiatives across the system. This includes developing key indicators that will help to determine the effectiveness of initiatives and whether they are reducing reoffending. It also reported developing a Youth Crime Trend Reporting Tool to provide key trends to the Community Safety Cabinet Committee. |

Recommendation 5 We recommend that the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, in collaboration with the Department of Youth Justice, finalises its system-wide monitoring and evaluation framework and commences evaluation of 2023 youth justice reforms. This should include:

|

Monitoring performance could be improved at an entity level

QPS does not have set targets and indicators to measure its performance against its youth justice strategy, nor does it report the outcomes of its youth justice programs regularly. The department has a range of mechanisms for monitoring its performance. It regularly reviews the performance of its service centres and undertakes other operational performance reviews. It can improve these by setting key performance indicators for service centres to drive further improvements.

The department has developed a framework for measuring the outcomes of programs that seek to rehabilitate young offenders.

Figure 4C is a case study about the department’s outcomes framework.

| The department’s outcomes framework |

|---|

In April 2022, the Department of Youth Justice developed a framework to measure the outcomes it achieves from programs and services. The framework identifies the primary needs of a young offender that must be addressed to reduce the likelihood of reoffending. These include their health and wellbeing, accommodation, employment, and education, and how connected they are to family, culture, and community. It also includes predictors of offending, such as attitudes, behaviours, and substance use. The framework clearly identifies the outcomes needed in the short, medium, and long term to reduce reoffending and increase public safety. The department is collecting data and is in early stages of reporting against the framework for selected programs. It intends to report performance against all programs and services in late 2024. |

Queensland Audit Office using data provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

We discuss the evaluation of specific youth justice programs and services in Chapter 6.

Recommendation 6 We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice formalises and executes a plan for measuring the effectiveness of programs using its outcomes framework. |

Reporting on youth crime could be more consistent and transparent

The department and the Queensland Government Statistician’s Office have published a range of youth crime statistics over the years. While these are useful to understand the demographics of young offenders, they do not shine a light on the number of serious repeat offenders or the effectiveness of the government’s actions to reduce crime by this cohort. The department has not consistently reported youth crime statistics, making it difficult to compare performance over time.

From 2015–16 to 2019–20, the department reported on the profile and complexities of young offenders, the types of offences they commit and the average number in custody. The department stopped this reporting until January 2024 when it released updated statistics.

In December 2023, the department also reported its performance against 3 service standards. This includes the proportion of young offenders declared by Childrens Courts as a serious repeat offender. While this is useful, the number of offenders that courts declare as serious repeat offenders is far lower than the number that the department identifies. As such, it does not provide an accurate reflection of the number of serious repeat offenders across the state. We discuss how entities identify and declare serious repeat offenders further in Chapter 6.

5. Investment in youth justice services

Knowing where to prioritise funding across Queensland’s youth justice system is vital. Decisions about where to invest should be based on risk and need, and informed by data. This should include detailed analysis of youth crime rates by location, types of offenders, offences and severity of offences, service provider capability, capacity, and other relevant trends. Macro analysis is also important in informing investment across the system. This includes balancing investment in programs that focus on early intervention with those that rehabilitate serious repeat offenders. This analysis can help to identify where there are gaps across the system and a need to build capability.

This chapter examines whether entities prioritise funding and resources based on key priorities and risks. It also examines how the Department of Youth Justice manages the contracts of service providers.

Are entities prioritising funding and resources based on key priorities and risks?

The Community Safety Cabinet Committee and the taskforce responsible for leading the system do not undertake system‑wide investment analysis to inform investment decisions. Nor does the department, who is responsible for investment in youth justice programs and services. As such, it is unclear how much is being spent on youth crime across the system, or whether funding is being invested in the right areas and programs. For example, the government has committed $104.6 million to the youth co-responder program for the period from 2019–20 to 2026–27. This program fills an important need and provides 24/7 support to young people at risk of offending. However, there is a lack of rationale to support investment in this program over other youth justice programs. We talk about the co-responder program further in Chapter 6.

Work in progress – system-wide investment analysis The Department of the Premier and Cabinet system-wide evaluation team has included system-wide investment analysis in its forward program of work. The Youth Justice Taskforce is also well positioned to analyse investment across the system given that it is responsible for whole-of-government strategic leadership. |

Entities need to do more to ensure their investment is prioritised based on risk

Across the system, entities need to do more to ensure they track their spend on youth justice and ensure investment is well planned and linked to risk. QPS captures some of its spend on youth justice but not all.

The department records its total spend in youth justice services and programs. Between 2018–19 and 2022–23, the department spent $1.38 billion on youth justice. This includes:

- $1.25 billion in internal programs and services, including costs associated with detention centres and service centres

- $134 million in outsourced programs and services (non-government organisations and First Nations‑led organisations).

The department analyses youth crime statistics to determine where to invest. However, it does not map its existing investment against youth crime trends to identify gaps. Nor does it assess investment across the system and consider how much it is spending on early intervention compared to reducing reoffending. As such, the department cannot be confident that it has the right types of programs in the right locations.

In 2015–16, the department mapped services across the state to inform its investment decisions. This included analysing the number of young offenders being case managed by its service centres, the capability and capacity of service providers, and other relevant problems and trends. The department has not repeated this mapping, and could not advise why it has not continued doing this important analysis.

The department is increasing its investment in non-government organisations that deliver youth justice services

The department has shifted its approach from primarily delivering youth justice services itself to engaging service providers in the community to deliver those services. Since 2019–20, the department has significantly increased its spend in non-government organisations that deliver rehabilitation programs and support services to young offenders and their families. Between 2018–19 and 2022–23, the department spent $134 million in service providers that deliver youth justice services. This included:

- 68 per cent ($92 million) in non-government organisations

- 32 per cent ($42 million) in First Nations-led organisations.

The department could not demonstrate that it is regularly testing the market

The department could not demonstrate that it is regularly testing the market when making its investment decisions. This increases the risk that its investments do not achieve value for money or meet the needs of young offenders.

The government’s procurement policy states that all procurement must achieve value for money.

Value for money means the best available outcome for money spent. To achieve value for money, entities must consider relevant government objectives and targets, whole-of-life costs, and non-cost factors such as supplier capability and capacity.

To achieve value for money, entities need to conduct market research, analyse supply and demand, and assess the level of competition in the supply market. This helps to inform whether it is necessary and beneficial to use:

- an open-offer procurement method, commonly referred to as testing the market. This provides opportunity for all interested suppliers to submit an offer

- a limited-offer procurement method and invite a supplier of its choice to offer. For example, using a limited-offer procurement method may be more appropriate if analysis shows there is only one service provider that can deliver a service in a required location.

The department invested $29 million in service providers between July 2022 to September 2023. It did not test the market for 60 per cent ($17 million) of these investments. This includes investments where it renewed contracts with existing service providers. The department advised that analysis was undertaken to support not testing the market in these instances; however, it could not provide evidence to support this work.

The rationale for funding decisions needs to be strengthened

Since 2018–19, the department has procured some services without adequately documenting the rationale for investment decisions. In these instances, it has not addressed key elements in the Queensland Government’s procurement policy. The policy states that a significant procurement plan must be developed for all significant procurement (the department defines significant procurements as those greater than $250,000). The plan must:

- include demand and supply market analysis

- develop procurement strategies and methods to achieve a value-for-money outcome

- develop performance measures and contract management arrangements

- identify and assess risks related to the procurement.

The department used a funding memorandum (in place of a significant procurement plan) for 7 significant procurements between March 2023 and September 2023 totalling $6.3 million. Funding memorandums do not address the elements listed above and fail to justify why the department is investing in certain providers. Some memorandums specifically noted that the procurement process could be strengthened by completing a market analysis. Of these 7 significant procurements, 5 were the result of direction and decisions from ministers rather than based on the department’s advice. These decisions, including who made the decision and the rationale for the decision, could have been documented more clearly. The department needs strong controls in place to ensure the minister is adequately briefed about the provider’s capability and the procurement risks.

We note that the department’s approach to procurement is an area that has been impacted by machinery of government changes. The department has had to adopt new policies and procedures for each of the 5 times the responsibility for youth justice has moved over the past 7 years.

Is the department managing the contracts of service providers effectively?

The department needs to strengthen its contract and performance‑management practices

In recent years, the department has revised its approach to focus on the outcomes achieved by service providers (such as helping to build stronger relationships within a family or better engagement in school or training programs). Funding is primarily contingent on outcomes achieved, not the delivery of outputs (such as time spent with young offenders). This shift encourages providers to prioritise quality service delivery, but it also comes with challenges, given outcomes can be difficult to measure and often long term in nature.

The department needs to strengthen how it monitors progress and service provider performance. While the department’s contracts with providers contain some performance measures, these were limited. They also do not include defined targets. Targets can help to hold service providers to account and drive improvement. The lack of targets is limiting the department’s ability to effectively manage any underperformance.

The department has several other mechanisms for assessing and managing the performance of service providers. These include holding regular meetings with service providers, reviewing information about the activities delivered by service providers, and seeking feedback from regional staff. A lack of clearly defined targets can make managing performance more challenging.

The department has begun to award longer contracts to service providers, in some cases of up to 5 years. The department’s rationale is to give providers confidence and help to build capability within the sector. Long contracts place emphasis on the need for proactive and effective performance-management practices. Under this approach, the department also needs to consider how it builds known capability gaps into contracts. Figure 5A is a case study about a service provider that had its contract renewed despite not meeting its obligations and outcomes.

| Renewing the contract of a service provider not meeting its contractual requirements |

|---|

In October 2019, the department engaged a service provider to deliver bail support to young offenders. Bail support services help to ensure young offenders meet the conditions of their bail. The service provider was funded $875,000 to deliver the service over 2 years. The contract stipulated that the service provider needed to report monthly about the young people it engaged with and about the outcomes of its work. In early 2021, regional staff reported concerns about the service provider’s performance, specifically its unwillingness to share information and work collaboratively with staff. As such, regional case workers chose to no longer refer young people to the service provider. It was difficult for the department to proactively address the poor performance without clearly defined performance targets. In April 2021, the department’s regional staff reviewed the service provider’s contract to determine whether to grant an extension. They concluded that extending the contract would not result in value for money and that it was necessary to test the market. The review included the following statements. 'There is an unacceptable risk in the fundamental disconnect between the organisation’s framework and the department’s statutory role.' 'Youth Justice is not receiving the bail support response intended by the funding and would receive more value for money by any other local bail support.' Despite the concerns raised, the review recommended that a one-year contract should be offered with changes to the contract’s terms. In July 2021, the department renewed the contract for another 4 years ($2 million), instead of the recommended one year. The department reported that this decision supported its current strategic direction. No further explanation was provided about how this contract supported the current strategic direction or provided value for money. |

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Department of Youth Justice.

Recommendation 7 We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice strengthens its investment and procurement practices to ensure that all investment decisions are based on sound market analysis, with the rationale for decisions clearly documented in line with evidence. This should include:

|

6. Rehabilitation and community safety

The first principle of the Youth Justice Act 1992 is to protect the community from offences and, in particular, from high-risk repeat offenders. These offenders often have complex needs and their offending behaviour can be triggered by many factors. Quickly and effectively assessing their needs and the risks they pose to the community is critical. Designing and delivering effective rehabilitation programs is equally important. Rehabilitating young offenders takes time. Entities need to understand the causes of their offending behaviour and deliver programs that address those needs.

Some young offenders continue to reoffend. In some cases, the nature and severity of their offending increases and they become a significant risk to the community. Judges and magistrates may order young offenders to be detained in a youth detention centre for a specific time (also referred to as a detention order).

Young offenders need appropriate plans and support when they leave detention and transition back into the community. This includes making sure they have a safe place to live and appropriate role models to support them through their transition period.

This chapter is about how effectively entities assess the risk and needs of serious repeat offenders and deliver effective rehabilitation programs. It also examines how entities are keeping communities safe, including how effectively the department rehabilitates young offenders in youth detention centres and supports them as they transition back into the community.

Do entities have a consistent and effective approach for identifying high-risk young offenders?

In 2022–23, serious repeat offenders committed 55 per cent of all youth crime in Queensland. It is, therefore, important that entities have a consistent and effective approach to identifying this cohort, and others who may pose a high risk. Good identification enables effective monitoring to inform strategies and coordinate activities. The Queensland Police Service (QPS) and the Department of Youth Justice (the department) do not have a consistent way of identifying those young offenders with the highest risk of reoffending.

Figure 6A shows the different approaches entities use to identify high-risk young offenders, including serious repeat offenders.

Entity | Description |

|---|---|

| QPS | QPS uses the Chronic Youth Offender Index to identify high-risk offenders and prioritise its response. It identifies the top 10 per cent of all offenders as high risk by calculating the number of charges, whether a weapon was used in the offending, the seriousness of the offending and whether the offender was on bail at the time of the offending. |

| The department | The department uses the Serious Repeat Offender Index to identify serious repeat offenders. The index considers a range of factors, including number of charges over the last 2 years, severity of offences, time spent in custody, and the young offender’s age. It also uses its risk assessment tool to assess the risk of individual young offenders. This is not utilised to identify broader cohorts of high-risk young offenders. |

Queensland Audit Office using information provided by the Queensland Police Service and the Department of Youth Justice.

In addition to this, the Childrens Court can declare that a young person is a serious repeat offender as part of their sentence.

QPS, the department, and the Childrens Court use these approaches for different purposes. However, the differing approaches mean they cannot, as part of the broader system, consistently identify the cohort most at risk of reoffending. For example, in July 2023, QPS identified 1,363 high-risk young offenders, while the department identified 440 young people as serious repeat offenders. The courts declared 48 young people as serious repeat offenders between March and December 2023.

The department uses its index to determine which young offenders it refers to multi-agency collaborative panels (MACPs). It also uses its index to determine which offenders need a 72-hour plan to help them transition from detention to the community. The department’s index identifies the cohort that has been charged with the most offences based on offending history, but it does not identify those most at risk of reoffending. While past offending may indicate future offending, other variables must be considered, including whether the young person is currently demonstrating aggressive and anti-social behaviour.

While the department has a tool to assess the risk of young offenders, it applies this to individuals only and does not use this to identify the cohort of young offenders across the state with the highest risk of reoffending. This assessment is not used to determine who should get referred to a MACP and get a 72‑hour plan. By solely using its index, the department increases the risk that some young offenders who are likely to reoffend may miss out on being collectively managed by MACPs and receiving the rehabilitation they need to address their offending behaviour.

The differing approaches between QPS, the department, and courts increase the risk of miscommunication. Entities need a consistent approach for identifying those young people at highest risk of reoffending. This approach needs to be defined, agreed to by all relevant entities, and integrated across the system.

Recommendation 8 We recommend that the Department of Youth Justice and the Queensland Police Service, in collaboration with relevant stakeholders and governance committees agree on a uniform, evidence-based approach to identifying those young offenders with the highest risk of reoffending and ensure this information is shared with relevant stakeholders across the system. |

Are the risks and needs of serious repeat offenders identified to inform their rehabilitation?

The risks and needs of young offenders need to be identified quickly and effectively, so entities can deliver rehabilitation programs that address the underlying causes of their behaviour. The department’s case workers are responsible for assessing the risk of young offenders.

The department uses an appropriate tool to assess the risk and needs of serious repeat offenders

The department uses the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory Tool (the tool) to assess the risk and needs of young offenders, including serious repeat offenders. The tool is informed by evidence and developed from an international model for assessing the risk and needs of young offenders. The department’s youth justice case workers use the tool to assess:

- the young offender’s risk to their own personal safety and the community, and the appropriate level of support

- the young offender’s criminogenic needs (the cause of the offender’s behaviour), enabling those needs to be targeted during case planning.

The tool indicates whether the young offender is a low, moderate, high, or very high risk. The higher the risk, the more likely it is that the young person will reoffend and the more support they will likely require.

The department does not consistently assess the risk and needs of serious repeat offenders before commencing rehabilitation

The department requires its case workers to assess the risk and needs of young offenders before they deliver rehabilitation programs. This helps to ensure they deliver the right type of rehabilitation at the right frequency. The department does not monitor whether risk assessments are being completed prior to programs commencing.

We examined whether the department assessed the risk of young offenders engaged in Intensive Case Management (ICM). ICM is one of the department’s core rehabilitation programs, delivered to high-risk young offenders and their families over 6–12 months.

Of the 276 young offenders engaged in ICM between 2018 and 2023, 10 per cent (28) did not have their risk and needs assessed, before starting the program. As a result, the department may be delivering ICM to young offenders who are lower risk, while more serious repeat offenders may be missing out.

The time taken to assess the risk and needs of serious repeat offenders is improving

The department is improving the time it takes to assess the risk and needs of serious repeat offenders, but more work is needed.

A case worker is required to assess the risk and needs of young offenders within 6 weeks of receiving a court order. They then reassess the young offender’s risk every 6 months.

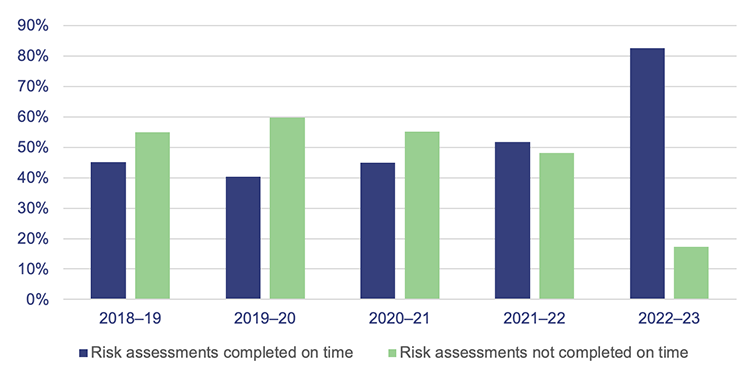

The department assessed the risk and needs of 2,417 serious repeat offenders between 2018–19 and 2022–23. Of these, only 56 per cent (1,364) were completed on time.

The percentage of risk assessments completed on time has increased from 45 per cent (155) in 2018–19 to 83 per cent (571) in 2022–23.

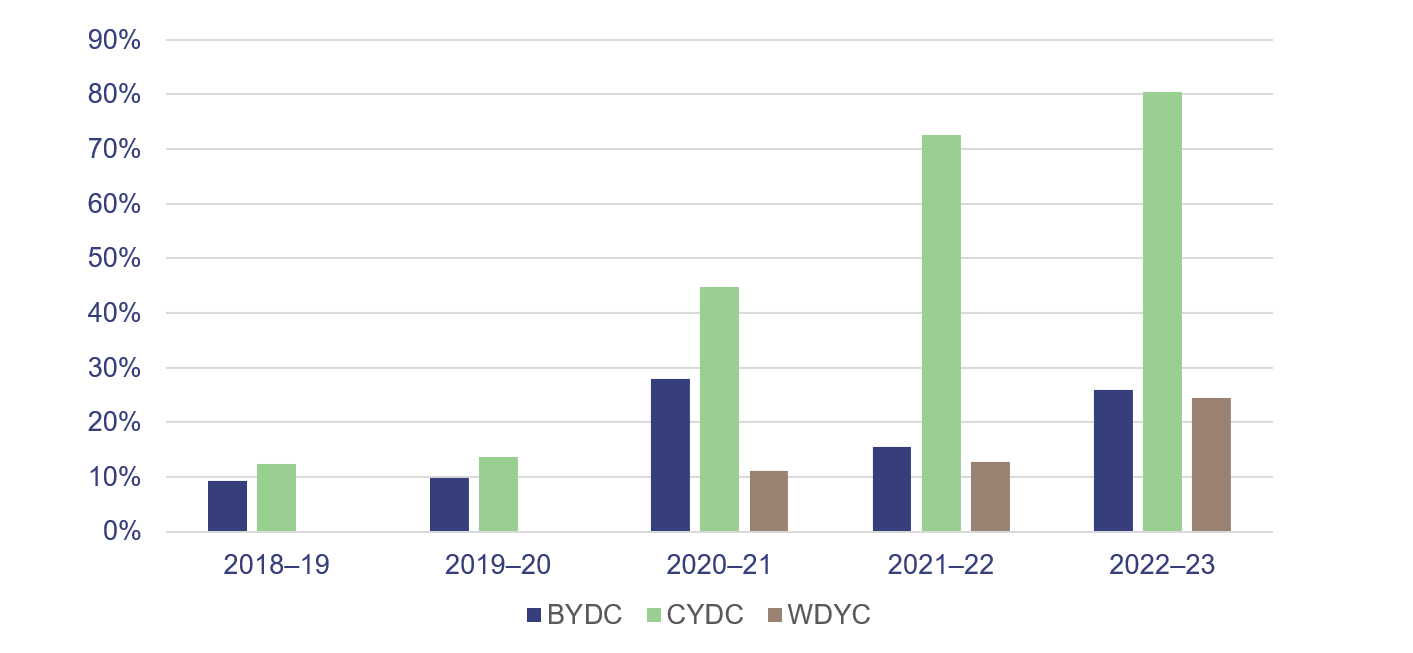

Figure 6B shows the percentage of risk assessments completed on time and those not completed on time for serious repeat offenders between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

Queensland Audit Office using data supplied by the Department of Youth Justice.

Of the 1,053 risk assessments not completed on time, 18 per cent (186) were completed 3 or more months after the due date. In these instances, the department cannot be sure it is delivering the right programs to serious repeat offenders to address the causes of their offending behaviour.

How are entities keeping communities safe and rehabilitating young offenders?