Overview

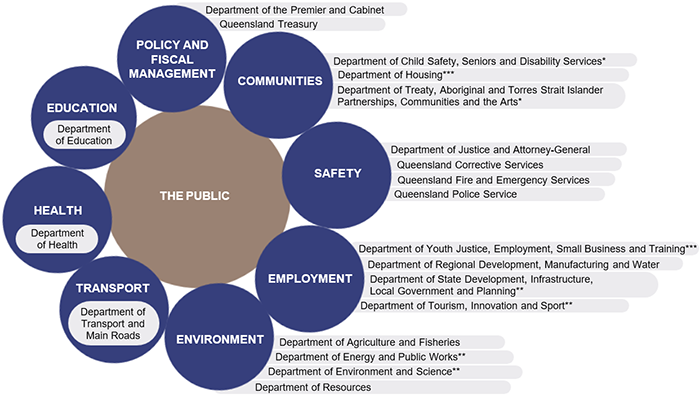

Most public sector entities prepare financial statements and table these in parliament each year. These entities, which include government departments, statutory bodies, government owned corporations, and controlled entities, provide a range of services across the state.

We also examine 3 areas we identified in our 2022–23 audit work with state entities that tie in with observations Professor Coaldrake made in his report, Let the sunshine in – Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector. These include some areas that Professor Coaldrake specifically recommended the Auditor-General continually monitor.

Tabled 21 March 2024.

Report on a page

This report summarises the audit results of 240 Queensland state government entities, including the 20 core government departments. It also analyses the consolidated financial performance of the Queensland Government (referred to as the ‘total state sector’) for 2022–23. Given the significance of the Olympic and Paralympic Games to the state, this report also provides an overview of the entities involved.

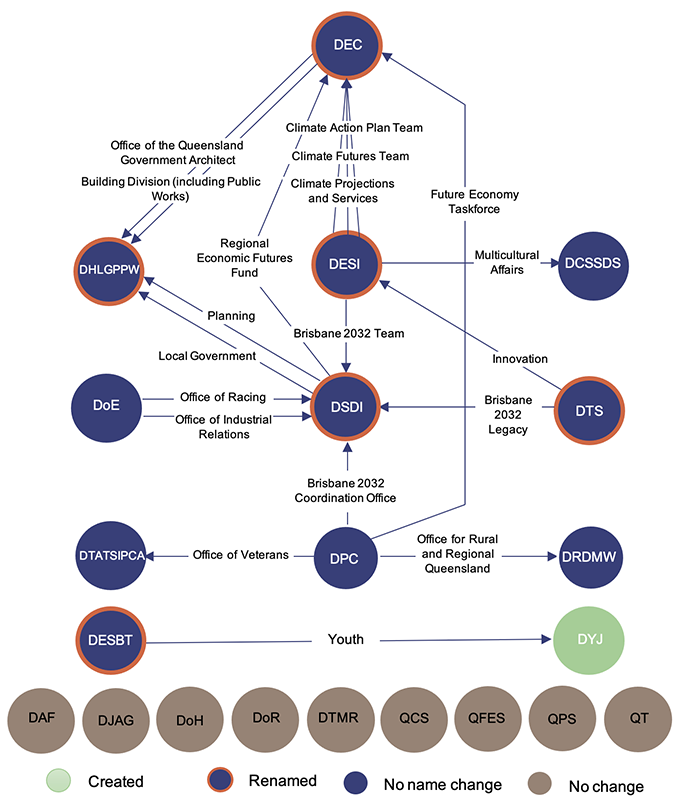

In May and December 2023, the state government announced machinery of government changes. The most recent changes took effect on 1 January 2024. As this report summarises the audit results of the 2022–23 financial year, we use the department names as at 30 June 2023.

Financial statements are reliable

In 2022–23, the financial statements of all departments, government owned corporations, most statutory bodies, and the entities they control were reliable and complied with relevant laws and standards. While some ministers tabled their financial statements earlier than in the past, the majority did not. This reduces the relevance of the financial information contained in their statements before it is released to the public.

Royalty revenue improves state’s finances

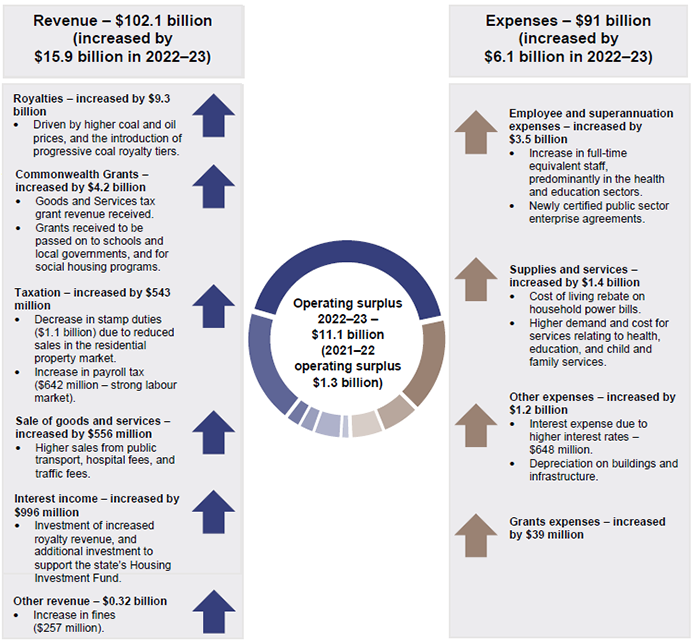

In 2022–23, the total state sector reported a net operating surplus of $11.1 billion (2021–22: a surplus of $1.3 billion). The significant increase in royalty revenue (money paid by mining companies to Queensland in exchange for the right to mine) for coal and oil was the main contributing factor.

Entities are not managing security risks posed by third‑party provider arrangements

We found entities are still not taking appropriate measures to ensure they fully understand and manage security risks posed by third parties providing services for their information systems.

We also found issues with entities’ internal controls (systems and processes) similar to those we have raised in previous years. These relate to information systems, payroll, and procurement. Entities need to focus on clearing outstanding issues from previous years.

Findings reflect Coaldrake observations on culture

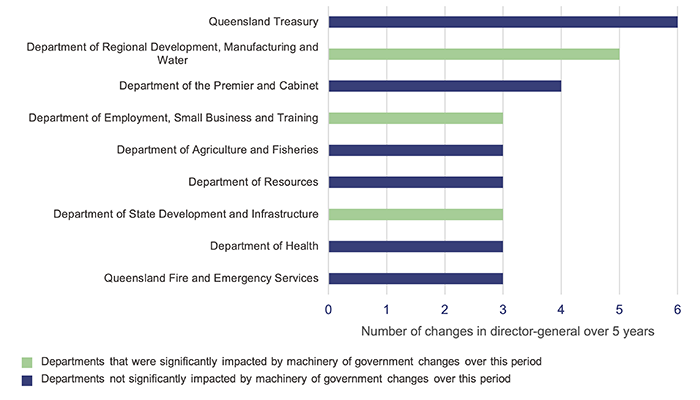

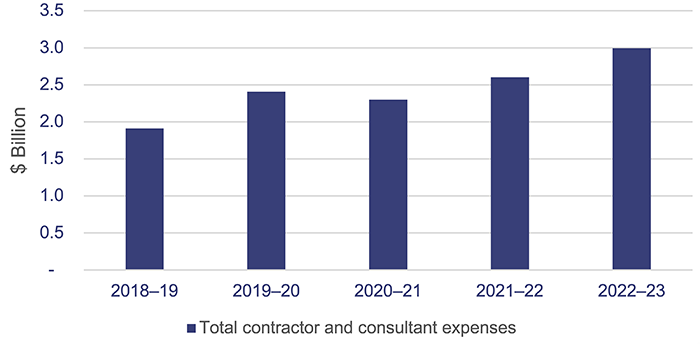

Professor Coaldrake’s report, Let the sunshine in, published in June 2022, commented on the culture of the Queensland public sector. Of direct relevance to his comments on culture, we found some departments have had at least 3 changes in director-general in the last 5 years, and contractor and consultancy costs have increased dramatically. More work is also needed to ensure special payments (not required by contract or legislation) are defensible and appropriate.

The second round of machinery of government changes for 2023 impacted 12 departments and 14 functions of government. This included re-establishing a Department of Youth Justice, last abolished in 2020. Youth Justice has now moved 5 times in 6 years. It also saw the new Brisbane 2032 Coordination Office move from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet to the Department of State Development and Infrastructure. The report recommending its creation said locating the office within a central agency was critical to mitigate the risk it would not receive the full attention and resources it needed. The new department will need to ensure that it does.

1. Recommendations for entities

We have identified the following recommendations.

|

Manage the cyber security risks associated with services provided by third parties (Chapter 5) |

|

We recommend that all entities: 1. implement a process to manage the security risks relating to third-party services for information systems and technologies, and introduce procedures that will

|

|

Implement robust policies and procedures to ensure special payments are appropriate, defensible, and transparent (Chapter 5) |

|

We recommend that all entities: 2. implement robust policies and procedures that specify when a special payment is appropriate and how it should be made. Guidance should outline who is authorised to approve special payments and what constitutes appropriate documentation to support

|

|

Improve awareness and understanding of guidance material available for special payments, including ex gratia payments (Chapter 5) |

|

We recommend that Queensland Treasury: 3. improves the awareness and understanding that all state entities have of guidance material available for special payments, including ex gratia payments. This should include

|

Status of recommendations made in State entities 2022

In State entities 2022 (Report 11: 2022–23), we recommended that audit committees actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses. While we have seen an improvement each year in the number of deficiencies we reported and their timely resolution, 20 per cent of the issues we raised with core departments in 2021–22 have not been resolved this year, and some issues are still outstanding from 2020–21.

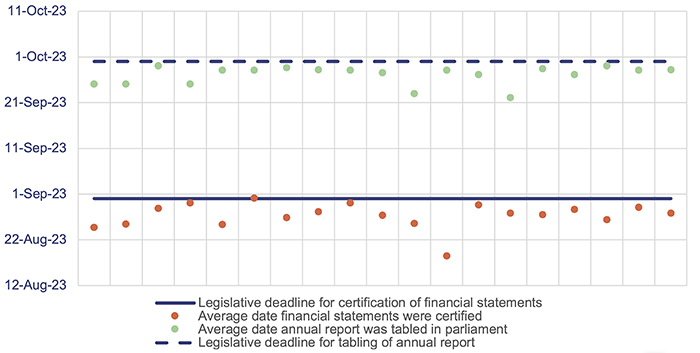

The timeliness of annual report tabling has only marginally improved, with only a slight reduction in the number of days between when financial reports are signed by management and audit and when they are tabled in parliament. We recommend entities and their respective ministers take action to improve timeliness of annual report tabling.

We have included a full list of prior year recommendations and their status in Appendix D.

Reference to comments

In accordance with s.64 of the Auditor-General Act 2009, we provided a copy of this report to relevant entities. In reaching our conclusions, we considered their views and represented them to the extent we deemed relevant and warranted. Any formal responses from the entities are at Appendix A.

2. Entities in this report

This report analyses the financial performance of the Queensland Government and includes the results of financial audits for all Queensland state government entities.

These entities are listed in Appendices E and I, where we group them by the new ministerial portfolios, following the December 2023 machinery of government changes. However, we continue to use the names of the former departments throughout the report as they were the entities we audited for 2022–23.

Notes: *These do not include entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General (see Appendix G), entities not preparing financial reports (see Appendix H), or entities audited by arrangement. **These are entities controlled by one or more public sector entity.

Queensland Audit Office.

Core departments

This report also includes our assessment of the controls over financial systems and processes for the 20 core departments existing in 2022–23, and identifies learnings for all state government entities. ‘Core’ departments are those gazetted as departments under the Public Sector Act 2022 and are responsible for most public services provided by departments. As our report focuses on the audit results for 2022–23, we refer to the 20 core departments that existed during this period. However, following machinery of government changes announced on 18 December 2023, the Department of Youth Justice was created, bringing the total core departments to 21 from 1 January 2024.

The other 7 departments were established under the Financial Accountability Act 2009. Examples include the Electoral Commission of Queensland, Legislative Assembly and parliamentary service, Office of the Governor, and the Public Sector Commission.

Note: *Renamed in May 2023. **Renamed in December 2023. ***Renamed in May 2023 and then again in December 2023.

Queensland Audit Office.

Our assessment of the financial reporting and internal controls of other Queensland state government entities, including energy and health, is included in the relevant sector reports on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au/reports-resources/reports-parliament.

How we present information

The departments in Figure 2B provide services across the state. The Queensland Audit Office’s dashboard, QAO Queensland, brings together important information about the finances and services of Queensland state and local government entities. In doing so, it uses 3 common ways to divide the state into regions:

- local government areas

- statistical areas (used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and by state entities to collect and report on information, including the state budget)

- hospital and health service areas.

This allows users to search by an address and identify the services and the financial results for their local area, including for councils, education, health, water, and electricity. The dashboard is available on our website at www.qao.qld.gov.au.

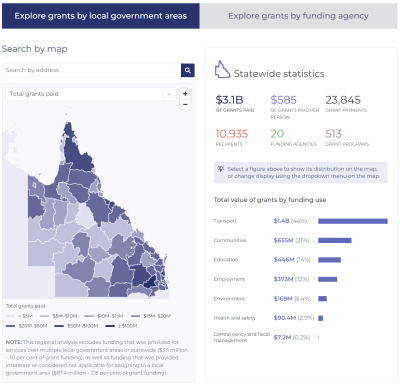

The following 2 data dashboards are also available on our website:

- water data visualisation – which includes drought status, primary industries, and water storage facilities (total capacity and storage level at 30 June, where publicly available)

- understanding grants dashboard – which explores information on grants paid by the Queensland Government and compares local government areas or explores the information by funding agency. This interactive tool uses public information available on the Queensland Government Open Data Portal to summarise the number and value of grants paid. It also categorises grants into funding uses, recipient types, and funding agencies.

Brisbane 2032 Olympics and Paralympics

On 21 July 2021, the Queensland Government, with the Brisbane City Council and the Australian Olympic Committee, signed the Olympic Host Contract with the International Olympic Committee, committing to host the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games (the Games).

New statutory body – responsible for games delivery

The Brisbane Organising Committee for the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games (the Brisbane 2032 Organising Committee) was established on 20 December 2021. It is responsible for organising and staging the Brisbane 2032 event under the Olympic Host Contract.

As its work will have a major impact on the state for most of the next decade, we have briefly explained its role and that of other, linked organisations in the following pages.

The Auditor-General issued an unmodified audit opinion on 31 August 2023. This means its financial statements can be relied upon. The statements covered the period 20 December 2021 to 30 June 2023 (as the organisation was exempt from preparing financial statements in its first year).

In June 2023, the organising committee received $15 million in funding from the International Olympic Committee, representing an advance of the broadcast rights contribution due under the Olympic Host Contract. Total expenditure for the period was $6.7 million, which was mainly employee costs, establishment costs, and board fees. There were 13.5 full-time equivalent employees as at 30 June 2023.

Figure 2C outlines the organising committee’s progress up until June 2023.

|

December 2021 |

The Brisbane Olympic and Paralympic Games Arrangements Act 2021 (Qld) was passed to establish the organising committee as a statutory body. After its establishment, the organising committee signed a joint agreement to be a party under the existing Olympic Host Contract with Brisbane City Council, the state government, and the International Olympic Committee. |

|

April 2022 |

The organising committee established a 22-person board with representatives from politics, finance, law, and entrepreneurship, and with voices championing accessibility, regional Queensland, First Nations, and representatives of sport. |

|

December 2022 |

The chief executive officer of the organising committee was appointed. |

|

June 2023 |

The organising committee held its first meeting with the International Olympic Committee’s Coordination Commission for Brisbane 2032. |

|

The organising committee received an advance payment of $15 million from the International Olympic Committee for broadcast rights. |

Queensland Audit Office.

Consultant appointed to advise on governance arrangements

Delivery partners for the Games include the Queensland Government, Australian Government, Council of Mayors (South East Queensland), Brisbane City Council, Council of the City of Gold Coast (City of Gold Coast), Sunshine Coast Council, Australian Olympic Committee, Paralympics Australia, and the Brisbane 2032 Organising Committee.

In early 2022, the delivery partners decided it was necessary to define roles, responsibilities, and governance arrangements. This was to ensure coordination and oversight for the planning and delivery responsibilities for the 3 levels of government.

In response, the Queensland Government, through the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, facilitated a tender process to procure strategic planning and development services. In May 2022, Deloitte was awarded the contract, valued at $717,000 (excluding goods and services tax). Under this contract, Deloitte produced a 16-page report following 25 consultation meetings (7 with Queensland Government lead agencies and 18 across the Games delivery partners) and one workshop.

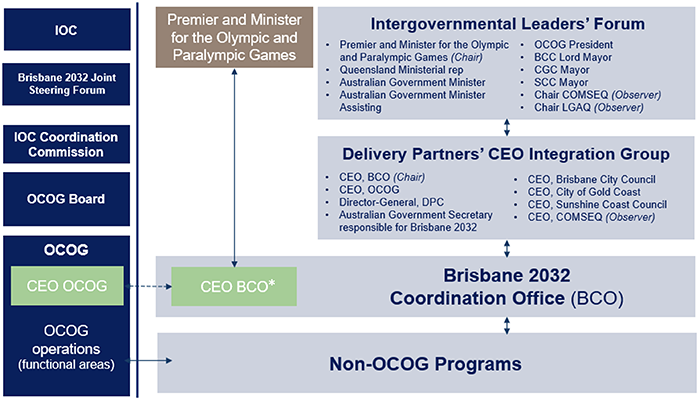

The final Brisbane 2032 Governance Arrangements report was delivered in February 2023, with the key recommendation being to establish a coordination office to provide central oversight on the progress and outputs of the programs being delivered (see Figure 2D below). We reviewed the tender process for this engagement as part of the 2023 financial audit and did not note any issues.

Following the state government’s announcement of machinery of government changes on 18 December 2023, the newly established Brisbane Coordination Office was moved from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet to the Department of State Development and Infrastructure. While the office will still exist in the new department, the report recommended that the office sit within the Department of the Premier and Cabinet as it was – ‘the critical agency in which it can receive both the attention of the Premier and Minister for the Olympic and Paralympic Games and the full resources, status and attention of the key central agency’. The report’s wording suggests that if the office sits outside of a central agency, then there is a risk that it may not receive the attention or resources it needs. The Department of State Development and Infrastructure will need to ensure it can mitigate this risk and consider if the report’s other recommendations are still relevant.

The value received from $717,000 of public money spent on this report is questionable, including following recent machinery of government changes. This will be explored further in a future performance audit on managing consultants and contractors as outlined in our Forward work plan 2023–26.

In Implementing machinery of government changes (Report 17: 2022–23), we reported that a challenge faced when transferring a function to another department is the risk a business unit will not fit the established culture, strategic priorities, and governance structure of the receiving department. Also, in 2023 status of Auditor-General’s recommendations (Report 3: 2023–24), we highlighted that recommendations to strengthen governance have been a theme in recent years.

The effectiveness of the Games governance arrangements will still be a focus of our future performance audit.

Creation of the governance model

The governance model Deloitte proposed in the report, which was accepted by the state government, is shown in Figure 2D. It included governance arrangements for non-OCOG programs (programs that the organising committee does not have primary delivery responsibility for (see Figure 2E)). It also recommended establishing the Brisbane 2032 Coordination Office within the Department of the Premier and Cabinet (DPC), which the government did in March 2023. However, the machinery of government changes in December 2023 transferred the office and non-OCOG programs to the Department of State Development and Infrastructure.

Notes:

* The 2022–23 annual report for the Department of the Premier and Cabinet shows that the Chief Executive Officer of Brisbane Coordination Office reports to the Premier and Minister for the Olympic and Paralympic Games via the Director-General of the department.

IOC – International Olympic Committee; BCO – Brisbane Coordination Office; OCOG – Organising Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games; CEO – chief executive officer; BCC – Brisbane City Council; CGC – City of Gold Coast; SCC – Sunshine Coast Council; COMSEQ – Council of Mayors for South East Queensland; LGAQ – Local Government Association Queensland; DPC – Department of the Premier and Cabinet; rep – representative.

OCOG means the Organising Committee of the Games, which was required to be created by the host city under the Olympic Host Contract. For Brisbane 2032 this is the new statutory body: the Brisbane Organising Committee for the 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

On 3 December 2023, Brisbane City Council’s Lord Mayor resigned from the Brisbane 2032 Olympic and Paralympic Games Intergovernmental Leaders’ Forum.

On 18 December 2023, the state government announced machinery of government changes that resulted in the Brisbane Coordination Office and non-OCOG programs transferring from the Department of the Premier and Cabinet to the Department of State Development and Infrastructure.

Brisbane 2032 Governance Arrangements: Brisbane 2032 Governance Arrangements Games Delivery Partner Report.

Intergovernmental Leaders’ Forum and Delivery Partners’ CEO Integration Group

These 2 groups link the work being undertaken by the Queensland Government, local governments, the Australian Government, and the organising committee. The role of these groups includes:

- informing the direction, planning, and delivery activities of the 3 levels of government for the Games

- ensuring Games delivery partners remain up to date on progress

- resolving complex, cross-partner issues.

Brisbane 2032 Coordination Office

The Brisbane 2032 Coordination Office (the Coordination Office) was established in March 2023, with a chief executive officer, who was accountable to the Director-General of the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, and (as shown in Figure 2D above) the former Premier and Minister for the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Coordination Office is responsible for coordinating the non-OCOG programs and ensuring that key stakeholders are informed of progress.

Following the December 2023 machinery of government changes, the Coordination Office’s roles and responsibilities, structure, and strategic priorities will need to be integrated into the new department (the Department of State Development and Infrastructure). The former Coordination Office’s Chief Executive Officer is now the Director-General of the new department.

DPC was expected to spend an additional $46 million to support the Coordination Office in 2023–24. As at 30 June 2023, there were 14 full-time equivalent employees in the Coordination Office (including an allocation of corporate staff), and it was budgeted to increase to 63 in 2023–24. The Department of State Development and Infrastructure will need to reassess if the proposed budget remains appropriate.

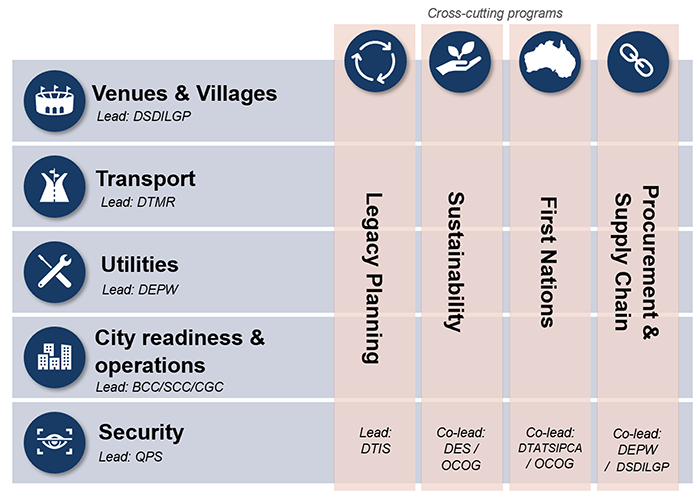

Non-OCOG programs

There are 9 programs that are primarily led by government partners, with the Sustainability and First Nations programs co-led by the organising committee. They are known as non-OCOG programs. Each covers a major component of the Games, as shown in Figure 2E. (Note this figure includes departmental acronyms that have changed since the recent machinery of government changes.)

The Coordination Office is responsible for overseeing all the planning and delivery of the 9 programs, in close collaboration with the Australian Olympic Committee, Paralympics Australia, and the organising committee.

Notes: DSDILGP – Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning*; DTMR – Department of Transport and Main Roads; DEPW – Department of Energy and Public Works*; BCC – Brisbane City Council; SCC – Sunshine Coast Council; CGC – City of Gold Coast; QPS – Queensland Police Service; DTIS – Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport*; DES – Department of Environment and Science*; OCOG – Organising Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games; DTATSIPCA – Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities and the Arts.

* Renamed since latest machinery of government changes became effective on 1 January 2024.

Following recent machinery of government changes, some of these programs now sit within the renamed Department of State Development and Infrastructure.

Department of the Premier and Cabinet.

Our continued focus on the Games

In the years leading up to the Games, we will continue to focus on the preparations. We will do so across several of our reports, including this, the annual state entities report.

We recently tabled our report Major projects 2023 (Report 7: 2023–24), which provided insights into the status of major infrastructure projects for the state and local governments, including projects relating to the delivery of the Games.

In 2024, we will table a performance audit specifically on preparing for the Games. It will provide insights into the initial preparation for Games delivery, with a deeper dive into the governance structure.

3. Financial performance of the Queensland Government

This chapter analyses the consolidated financial performance of the Queensland Government (the ‘total state sector’) for 2022–23.

The Financial Accountability Act 2009 requires the Treasurer to prepare annual consolidated financial statements for the Queensland Government. The Auditor-General issued an unmodified audit opinion on the Queensland Government’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements on 17 October 2023, which means the financial statements can be relied upon.

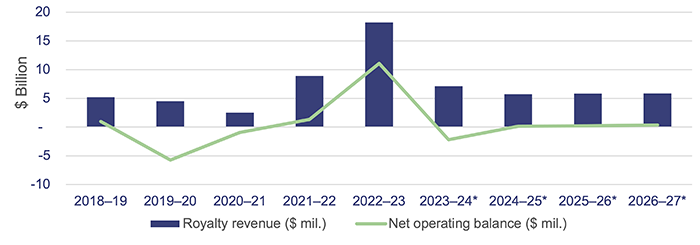

Royalty revenue is a major contributor to the significant improvement in the state’s financial performance

In 2022–23, the total state sector reported a net operating surplus of $11.1 billion (2021–22: $1.3 billion surplus). The improved financial performance of the state was mainly due to significant increases in royalty revenue through:

- an increase in global coal and oil prices

- the introduction by the Queensland Government of 3 new tiers to the coal royalty structure, announced as part of the 2022–23 state budget.

The Queensland Government receives royalty revenue from mining companies who extract coal, metals, petroleum and gas, and other minerals.

While Queensland’s previous royalty regime stopped at 15 per cent for prices above $150 a tonne, the new system includes royalty rates of 20 per cent for prices above $175 a tonne, 30 per cent for prices above $225 a tonne, and 40 per cent for prices above $300 a tonne.

Figure 3A shows the movement in royalty revenue over the past 5 years, and its impact on the net operating balance for the general government sector (government departments and other non-trading government entities such as hospital and health services). The ‘net operating balance’ is a key measure of financial performance. It compares the revenue earned by the Queensland Government to the expenses it incurs on day-to-day operations. The graph also shows the forecast to 2026–27.

Queensland’s revenue is sensitive to market conditions that the government cannot control. While positive market conditions continue, it is important that the government continues to invest wisely and plan for future uncertainty in revenue.

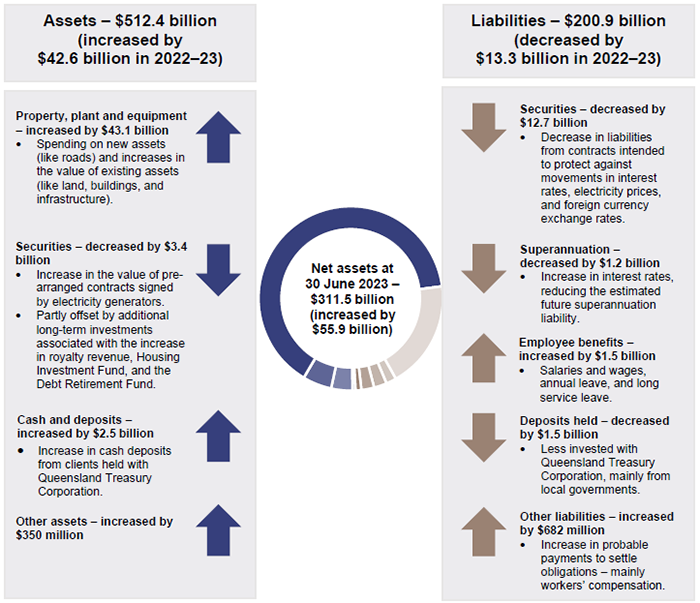

As at 30 June 2023, the total state sector reported a net worth of $311.5 billion (an increase of $55.9 billion on last year). This was mainly due to increased spending on new assets and increases in the value of existing physical assets – including land, roads, school buildings, and land under roads.

Figure 3B provides an overview of movements in the state’s financial results.

Queensland Audit Office from the 2022–23 Report on State Finances of the Queensland Government.

Climate and sustainability reporting

There has been an increased focus on climate and sustainability reporting both in Australia and overseas as entities and governments work to better understand the requirements and other considerations for climate and sustainability reporting entities.

The Queensland Government’s 2022–23 consolidated financial statements include a high-level summary of, and reference to, the Queensland Sustainability Report, which outlines the Queensland Government’s approach to managing climate-related risks.

Queensland Treasury’s approach for Queensland public sector entities under its regulation is not to mandate disclosures at the individual agency. Instead, its focus has been on whole-of-government reporting, as governance, strategy, and risk management of climate-related risks is largely set at a whole‑of‑government level.

At the date of this report, Queensland Treasury has not decided whether to have the Queensland Sustainability Report assured.

In addition to the Queensland Sustainability Report, the state’s approach to addressing sustainability‑related risks is supported by the:

- Queensland Climate Action Plan 2020–2030 – which details targets that the Queensland Government has set to reduce emissions

- Queensland Energy and Jobs Plan – which outlines how Queensland’s energy system will transform to deliver clean, reliable, and affordable energy to provide power

- Queensland Climate Adaption Strategy – which is a central component of Queensland’s climate change response. It guides the state’s transition towards a zero net emissions economy, including consideration of climate risks and opportunities.

The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) was established in November 2021 to develop global standards for entities in disclosing climate-related financial information for the users of financial statements.

In June 2023, the ISSB issued its first 2 standards – IFRS S1 General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-related Financial Information and IFRS S2 Climate-related Disclosures.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) will be responsible for issuing the Australian equivalents of the ISSB standards. The AASB will need to adapt the standards for not-for-profit and public sector entities, as the ISSB standards were developed for private sector entities. It will be up to individual jurisdictions to mandate the application of Australian sustainability standards.

In October 2023, the AASB released Exposure Draft SR1 Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards (ASRS) 1 General requirements for Disclosure of Climate-related Financial Information for public feedback. The AASB’s approach is to take a ‘climate first’ approach and is proposing that references to sustainability in the ISSB standards be replaced with ‘climate-related’ in the Australian equivalents.

The AASB is currently working with the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board in developing an International Standard on Sustainability Assurance 5000 General Requirements for Sustainability Assurance Engagements and the Australian equivalent.

In January 2024, the Commonwealth Treasury issued proposed legislation to mandate application of climate-related financial disclosures (and applicable assurance requirements) to entities reporting under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). These proposals are expected to affect many Queensland government owned corporations (GOCs).

Queensland Treasury is currently evaluating how the content of the proposed ASRS and ISSB standards will apply to Queensland Government agencies. It will be up to Queensland Treasury to determine application to entities under its jurisdiction, such as departments and statutory bodies.

4. Results of our audits

This chapter provides an overview of the audit opinions we issued for Queensland state government entities. It also provides an update on their timeliness in tabling annual reports and making financial statements available to the Queensland community.

Chapter snapshot

Audit opinion results

We issued unmodified opinions for 97.6 per cent of the 2022–23 financial statements we audited (2021–22: 97.9 per cent) as at 18 March 2024. All the departments, government owned corporations, and most of the statutory bodies received unmodified audit opinions, which indicates the results reported in their financial statements can be relied upon.

We express an unmodified opinion when financial statements are prepared in accordance with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards.

Most entities (91 per cent) had their audit opinions signed within their legislative deadlines (2021–22: 82.6 per cent).

Figure 4A summarises the audit opinions we issued for 247 entities for their 2022–23 financial statements, while Appendix E provides the details. Appendix I provides the list of entities for whom audit opinions have not yet been issued.

|

Entity type |

Unmodified opinions |

Modified opinions |

Opinions not yet issued |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Departments and entities they control (controlled entities) |

39 |

– |

– |

|

Government owned corporations and controlled entities |

26 |

– |

– |

|

Statutory bodies and controlled entities |

122 |

6 |

5 |

|

Jointly controlled entities |

40 |

– |

2 |

|

Entities audited by arrangement |

14 |

– |

– |

|

Total |

241 |

6 |

7 |

Queensland Audit Office.

We included an emphasis of matter in our audit reports on 43 financial statements (2021–22: 46).

We include an emphasis of matter to highlight an issue of which we believe the users of financial statements need to be aware. The inclusion of an emphasis of matter paragraph does not change the audit opinion.

We did this to highlight:

- 38 entities where only certain accounting standards were used in the preparation of financial reports, and where these financial reports were only of interest to a small group of users

- 4 small entities that faced uncertainty regarding their ability to pay their debts as and when they fell due

- 7 entities that had either ceased operations or were likely to be dissolved in the coming year.

At times, we issue more than one emphasis of matter for an entity.

Modified audit opinions

We issued 6 modified opinions in 2022–23 (2021–22: 5).

We express a modified opinion when financial statements do not comply with the relevant legislative requirements and Australian accounting standards and as a result, are not accurate and reliable.

There are 3 types of modified opinions: qualified, adverse, and disclaimer.

Appendix E lists the 6 entities for which we issued modified opinions. These are small entities – category 2 water boards, water authorities, or drainage boards.

We issued 4 qualified opinions, which we do when the financial statements comply with relevant accounting standards and legislative requirements, except for a specified area. These qualifications related to:

- entities’ valuation of property, plant and equipment and intangible assets

- entities’ ability to prove the existence of property, plant and equipment and intangible assets (for example, internally generated software)

- uncertainty as to whether debtors will pay all amounts that they owe, and as a result, whether the value of receivables in the financial statements are accurate.

We disclaimed 2 opinions, which means we were unable to express an opinion as to whether the financial statements complied with the requirements of the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2019 or the minimum reporting requirements published by Queensland Treasury.

Opinions not yet issued

Appendix I lists those entities whose audits are not yet complete. These are small entities, and most are category 2 water boards, water authorities, or river improvement trusts that did not meet the legislative deadline of 31 August.

Finalisation of overdue financial statements

We also issued 10 of the 28 audit opinions for financial statements from prior years that were outstanding as at 28 February 2023. The remaining 18 continued to be outstanding as at 18 March 2024. Of these, the audit opinion for one water authority has been outstanding since 2015–16, and for a river improvement trust since 2017–18.

The 10 audit opinions we issued included 4 qualified opinions on small water boards, relating to the completeness, existence, and valuation of property, plant and equipment. One of these qualified opinions also highlighted an entity’s failure to comply with the requirements of the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2019 and minimum reporting requirements published by Queensland Treasury. Appendix J provides details about these audit opinions.

Other audit certifications

Appendix F lists the other audit and assurance opinions we issued, including:

- those requested by entities – to provide assurance over internal controls (systems and processes) at shared service providers, which deliver payroll, accounts payable, and information technology services to entities

- to meet reporting requirements for grant agreements (funding from state and federal governments) and regulatory information notices (which are used to collect information from energy distribution entities to assist the Australian Energy Regulator in deciding how much these entities can earn)

- to meet compliance requirements under legislation, including those for Australian financial services licences. (Certain entities must hold a financial services licence to issue or manage financial products or deal in certain investments.)

Entities exempted from audit by the Auditor-General

This year, 6 Queensland state government entities were exempted from audit by the Auditor-General (2021–22: 6). This occurs for foreign-based controlled entities where the Auditor-General has no jurisdiction or when the Auditor-General deems an entity to be small and of low risk to the financial position of the Queensland Government as a whole.

Exempt entities are still required to engage an appropriately qualified person to audit their financial statements. Appendix G lists the entities, and the reasons for their exemptions.

Entities not preparing financial statements

Not all Queensland public sector entities produce financial statements. This year, 173 entities were not required, either by legislation or the accounting standards, to prepare financial statements (2021–22: 142). We have identified them in Appendix H.

Machinery of government changes can affect the preparation of financial statements

Restructures of government functions (and the associated re-allocation of resources and people between departments) are referred to as ‘machinery of government’ changes.

On 18 May 2023, as a result of machinery of government changes, 11 functions were transferred between 10 departments. The remaining 10 departments were not impacted.

All affected departments had their financial statements certified by the legislative date of 31 August 2023, but 2 of the 10 were unable to provide draft financial statements to us by the agreed dates.

These departments have a history of providing financial statements and working papers on time. The impact of the machinery of government changes, effective from 1 June 2023, shifted their attention to the implementation of necessary changes. This had a significant impact on their timely preparation of quality draft financial statements and put more pressure on these finance teams to deliver their financial statements in time to meet the statutory deadline.

Further changes

On 15 December 2023, the Honourable Stephen Miles was appointed as Queensland’s 40th Premier. Following his appointment, the state government announced machinery of government changes on 18 December 2023 to come into effect on 1 January 2024. These changes transferred 13 functions between 12 departments. The remaining 9 departments were not impacted.

Changes included creating another Department of Youth Justice, which was last abolished back in 2020. This function has moved 5 times in 6 years. Figure 4B shows the most recent machinery of government changes.

|

DAF – Department of Agriculture and Fisheries |

DCSSDS – Department of Child Safety, Seniors and Disability Services |

|

DEC – Department of Energy and Climate |

DESI – Department of Environment, Science and Innovation |

|

DESBT – Department of Employment, Small Business and Training |

DHLGPPW – Department of Housing, Local Government, Planning and Public Works |

|

DJAG – Department of Justice and Attorney-General |

DoE – Department of Education |

|

DoH – Department of Health |

DoR – Department of Resources |

|

DPC – Department of the Premier and Cabinet |

DRDMW – Department of Regional Development, Manufacturing and Water |

|

DSDI – Department of State Development and Infrastructure |

DTATSIPCA – Department of Treaty, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships, Communities and the Arts |

|

DTMR – Department of Transport and Main Roads |

DTS – Department of Tourism and Sport |

|

DYJ – Department of Youth Justice |

QCS – Queensland Corrective Services |

|

QFES – Queensland Fire and Emergency Services |

QPS – Queensland Police Service |

|

QT – Queensland Treasury |

|

Queensland Audit Office.

Ministers should continue to table their annual reports earlier

Accurate and timely reporting, including publishing financial statements as soon as they are available, is integral to good governance. This will be even more important in 2024, in the lead up to the Queensland state election.

Since 2021, we have seen gradual improvements in the time taken to table annual reports (which included financial statements), and this trend continued in 2023.

Figure 4C shows the timing of 2022–23 financial statement certification and annual report tabling for state entities by ministerial portfolio (each column in the graph represents one ministerial portfolio). The annual reports of all state entities (departments, government owned corporations, and statutory bodies, excluding category 2 water boards, river improvement trusts, and drainage boards, due to their small size) were tabled before the legislative deadline of 30 September 2023. However, there was an average of 31.8 days (32.8 days in 2021–22) between the date financial statements were certified and when entities tabled their annual reports across all portfolios.

The delay is because ministers are required by legislation to table the annual reports of these entities – including their financial statements – in parliament within 3 months of the end of the financial year. Until they do this, the departments, statutory bodies, and government owned corporations are not able to publish their financial information. However, entities should work with their respective ministers to improve the timeliness of annual report tabling.

Note: Each column represents one ministerial portfolio.

Queensland Audit Office.

Delays in publishing financial statements reduce their usefulness to parliament and the public. Events may also occur between the date of signing and the date of tabling that require the financial statements to be reassessed and possibly re-signed.

This will become critical as we approach the next election, when key decision-makers, stakeholders, and the public will demand timely reports so they can accurately assess and measure the performance of government.

We have made recommendations on this issue before. Appendix D provides a status update on this, and on other recommendations we have made in previous years.

5. Internal controls at state entities

Internal controls are the people, systems, and processes that ensure an entity can achieve its objectives, prepare reliable financial reports, and comply with applicable laws. Features of an effective internal control environment include:

- a strong governance framework that promotes accountability and supports strategic and operational objectives

- secure information systems that maintain data integrity

- robust policies and procedures, including appropriate financial delegations

- regular management monitoring and internal audit reviews.

This chapter reports on the effectiveness of Queensland state entities’ internal controls and provides areas of focus for them to improve on. While we concentrate mainly on large departments, we have identified common issues that all entities should consider.

When we identify weaknesses in the controls, we categorise them as either deficiencies or significant deficiencies.

A deficiency arises when internal controls are ineffective or missing, and are unable to prevent, or detect and correct, misstatements in the financial statements. A deficiency may also result in non-compliance with policies and applicable laws and regulations and/or inappropriate use of public resources.

A significant deficiency is a deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal controls that requires immediate remedial action.

In this chapter, we also draw parallels between some of our findings and the observations made by Professor Coaldrake in his 2022 report Let the sunshine in – Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector.

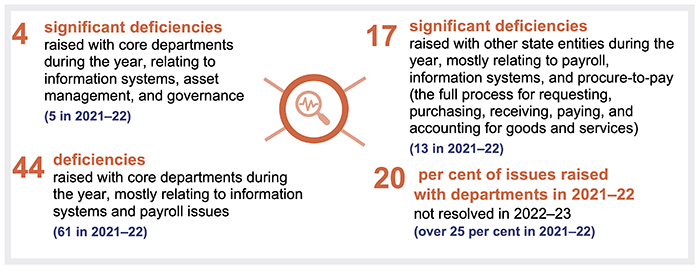

Chapter snapshot

Internal controls are generally effective, but entities still have common weaknesses

Each year, we assess whether the internal controls used by entities to prepare financial statements are reliable, and we report any deficiencies in their design or operation to management for action.

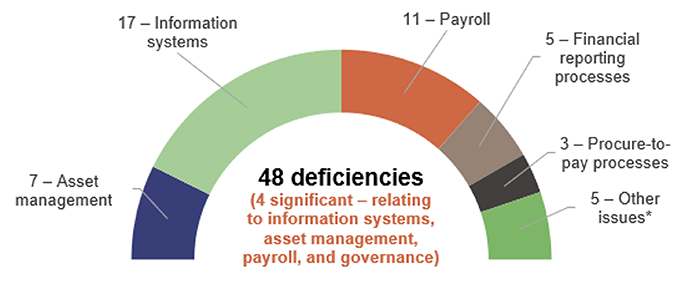

Overall, we found that the internal controls state entities have in place are generally effective, but they can be improved. We reported fewer deficiencies to departments this year than we did last year, but some common weaknesses continued. Of the deficiencies we identified, we assessed 4 as significant.

Figure 5A shows the types of deficiencies we identified in core departments.

Note: *Other issues relate to grants management, monitoring of controls, and governance.

Queensland Audit Office.

Each entity notified us of the corrective action it planned to take to address the internal control issues we raised. We are satisfied with these and with the entities’ proposed implementation time frames. Of the 48 deficiencies we raised with core departments, 16 have been resolved, and work is underway to address the remaining 32.

While we have seen an improvement in the number of deficiencies we report annually and their timely resolution, 20 per cent of the issues we raised with core departments in 2021–22 have not been resolved this year, and some issues are still outstanding from 2020–21.

Of the 45 issues from the prior year that were outstanding at the beginning of the year, departments revised the action date for resolution of 27 during the year. Also, we raised 4 issues in 2021–22 that we re-raised and reported to management again in 2022–23. These are yet to be resolved.

Proactive and timely resolution of deficiencies indicates a strong foundation for the effective operation of internal controls. Consistent with last year, we continue to recommend that audit committees actively monitor the implementation of audit recommendations and encourage the timely resolution of outstanding internal control weaknesses. Appendix D provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

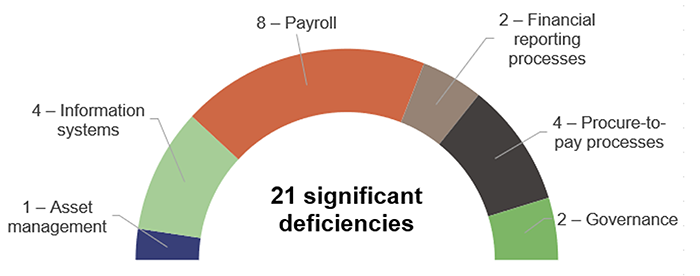

Issues identified across state entities that need immediate attention

We reported 21 new significant deficiencies across all state entities (including departments, statutory bodies, and government owned corporations) this year. Of the 21 significant deficiencies we raised, only one has been resolved, with work underway to act on the remainder.

Figure 5B shows the types of significant deficiencies we reported to state entities. We observed an increase in the number of significant deficiencies. We also observed several common issues that require immediate action across the sector.

Queensland Audit Office.

Common issues across the state sector

In the following paragraphs, we report on the deficiencies we identified in core departments, then expand on these in relation to information systems, the use of shared service providers, payroll, procurement, and governance. We also report specifically on those issues that require immediate action by entities across the total state sector.

Departments need to effectively protect their information systems from external attacks and be able to respond and recover

The Annual Cyber Threat Report 2022 from the Australian Cyber Security Centre identified the government sector as being one of the main targets for cyber security incidents. This is due to the large volumes of data it holds and its operation of critical infrastructure assets. If government systems were successfully infiltrated, the sector could be exposed to operational disruption and reputational damage.

Since October 2018, the Queensland Government’s Chief Digital Officer has required departments to:

- implement an information security management system (ISMS)

- report on their progress in doing so.

An ISMS is a systematic approach to identifying and managing information security risks, in accordance with the ISO27001 information security standard.

Over the past 5 years, the ISMS maturity of the Queensland Government has improved. In 2022–23, 86 per cent of departments reported an operating level ISMS (where risks are identified, managed, and continuously improved) against the target of 100 per cent set by the Queensland Government Chief Digital Officer. This was an improvement from the 2021–22 result, where 73 per cent of departments reported an operating level ISMS.

The improvement in ISMS maturity indicates that departments have established governance, processes, and technical controls for information security. They need to remain vigilant when managing their information security, as the global security landscape is constantly evolving.

Departments need to improve how they monitor the security of third-party systems

Departments rely on other organisations (third parties) for information system services and technologies when delivering their services to the public. These organisations are now part of the departments’ frameworks for protecting, responding, and recovering from external attacks.

There have been some high-profile attacks on the third-party systems with impacts on Queensland public sector entities in recent years. This is one of the emerging and significant risks in managing cyber security.

This year, we reported a significant deficiency relating to a failure to manage security risks stemming from the use of 2 external third-party systems. Departments need to have robust processes to assess how well their third-party service providers are managing the security of their systems and their ability to respond to security incidents.

We are finalising a performance audit on insights into and lessons learnt from entities’ preparedness for responding to and recovering from cyber attacks. We encourage entities to review this report when it is tabled and implement any recommendations relevant to them.

In our Forward work plan 2023–26, we have stated we will undertake an audit on managing third-party cyber security risks. It will examine how effectively the Queensland Government identifies third parties with access to its data and networks, assesses related security vulnerabilities, establishes relevant controls, and minimises the impact of third-party security breaches.

|

Recommendation 1 (all entities) Manage the cyber security risks associated with services provided by third parties. We recommend that all entities implement a process to manage the security risks relating to third-party services for information systems and technologies, and introduce procedures that will:

|

Common information system control weaknesses continue

We continue to identify some common weaknesses in our reviews of information system security. We frequently find that some users are provided with full access to information systems when their job responsibilities do not require it. This may allow users to make significant changes to the system, bypass security settings, or access sensitive information.

Third-party service providers are also usually provided with access to system administration functions. As we identified in prior years, departments are putting their information systems at risk by not implementing:

- appropriate security controls for managing access to system administration

- processes that drive continuous improvement.

This year, we also identified a significant deficiency relating to a new system that was implemented before it was adequately tested. A post-implementation review of the system highlighted high-risk issues.

Consistent with previous years, we recommend that departments continue to act on our recommendation to strengthen the security of their information systems.

Entities need to better manage and check their arrangements with shared service providers

Most of the departments use a shared service provider to provide a range of payroll, accounts payable, and information technology infrastructure services. The shared service providers process transactions on behalf of departments, but the departments are responsible for ensuring they have complementary controls in place and that these are operating effectively.

Each department has a service level agreement with its shared service provider. The shared service provider has a service catalogue that sets out its responsibility, the department’s responsibility, and the performance standards to be met. Several of the performance standards are linked back to an agreed schedule, which is attached to the individual service level agreements.

This year, we identified deficiencies relating to key general ledger reconciliations (such as payroll) not being prepared or reviewed in a timely manner. Most of these issues involved reconciliations that are prepared by a shared service provider.

The shared service provider is responsible for reconciling (re-checking) key general ledger accounts and providing the reconciliations to the departments for their review. We identified instances where reconciliations for some months had not been prepared and provided to departments in a timely manner after month end, with some including significant unreconciled items. While departments and the service provider had agreed on time frames, the provider had insufficient staffing to meet the agreed milestones.

The departments worked with the shared service provider to follow up on the delays, and some departments performed alternative procedures to identify any abnormalities during these months. This highlights the importance of departments monitoring performance time frames and holding the service provider accountable where the agreed standards are not met. Departments need to have back-up plans and compensating controls (that provide equivalent or comparable protection) in place when the service provider cannot provide the agreed services.

Entities need to strengthen their payroll controls

This year, we again identified weaknesses in payroll controls, including 8 significant deficiencies we reported to state entities. The significant deficiencies related to:

- performance payments that were paid to employees before a performance review process was completed and documented, which was not compliant with the entity’s performance incentive policy

- a remuneration increase for a chief executive without evidence to support how the amount was calculated, the decision to make the payment, or its approval

- employee rosters that were not approved by the correct delegate, or were incomplete, but still processed. In these cases, other key controls to detect roster variations or errors, such as forms used to approve overtime, were also ineffective. We identified a range of irregularities and deviations compared to internal policy requirements

- errors in payroll processing that resulted in instances of over- and underpayment of employee payments, including the use of incorrect allowance rates in the payroll system

- leave requests and extensions of employee appointments that were processed before appropriate approvals were obtained

- termination payments made to senior management that were not in accordance with internal policies or entitlements outlined in employee contracts.

Other common deficiencies we identified across core departments included:

- no review of payroll monitoring reports. In one case, we identified overpayments to an employee that would have been identified earlier if the department had been performing regular reviews of payroll monitoring reports

- a lack of or untimely review and approval of key employee transactions, such as higher duties, hours worked, and overtime claims.

For some departments, we have re-raised the same deficiencies multiple times, with the departments yet to resolve these issues.

Without the timely and appropriate review of key payroll reports, and consistent completion of key payroll processes and documents, there is an increased risk that errors or invalid payments may not be detected.

Consistent with previous years, we continue to recommend that entities ensure payroll reports are regularly reviewed, and that employees consistently comply with internal policies and manuals that outline payroll processes. Appendix D provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

Entities need to improve their procure-to-pay processes

This year, we again identified weaknesses in procure-to-pay practices (processes for requesting, purchasing, receiving, paying, and accounting for goods and services) across state entities. Among them were 5 significant deficiencies, including:

- non-compliance with the Queensland Procurement Policy, when an entity’s procurement policy did not require procurement arrangements to be put to tender

- unclear policies and procedures for outlining what constitutes appropriate business expenditure and when it is appropriate to incur entertainment or catering expenditure for business purposes

- weaknesses in managing conflicts of interest in procurement processes, and non-compliance with internal procurement policies, including undeclared conflicts of interest on declaration forms and a failure to assess completed declarations prior to executing a contract

- a statutory body hiring an employee to work for them who also worked for a private company that was led by a member of the statutory body’s key management personnel. This work was paid for by the statutory body and eventually reimbursed by the private company towards the completion of our audit. The member of key management personnel excused themselves from the recruitment process, but as the only delegated authority, they authorised the employment contract, without declaring this relationship in the conflicts register. While they later updated the register for the relationship, this failure to declare increased the risk of a perceived conflict of interest.

Under the Statutory Bodies Financial Arrangements Act 1982, funding the salary of an employee (lending an amount) to work for a private company led by a member of its key management personnel constitutes a loan. The statutory body did not seek the required Treasurer’s approval for this arrangement - invoices paid twice due to insufficient checks performed over previous payments prior to releasing funds.

To achieve value for money from their purchasing activities and to ensure compliance with the Queensland Procurement Policy 2021, entities need effective procurement and contract management practices, supported by current policies and manuals.

Consistent with last year, we continue to recommend all entities ensure they have appropriate policies and manuals to support their procurement and contract management practices. This should include giving clear guidance for staff to follow when making procurement decisions. Appendix D provides a full list of prior year recommendations and their status as at 30 June 2023.

Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector

In February 2022, the Queensland Premier appointed Professor Peter Coaldrake OAM to conduct a review into the culture and accountability of the state public sector. In June 2022, Professor Coaldrake issued his final report – Let the sunshine in – Review of culture and accountability in the Queensland public sector. The report raised concerns over the accountability, transparency, and integrity of the state sector, and its failure to meet the public’s expectations.

The Coaldrake report identified a number of areas that he suggested be subject to regular monitoring by the Auditor-General. This included the engagement of consultants and contractors by departments, and the outcome of lobbyist communications.

In our Forward work plan 2023–26, we have highlighted 3 proposed audits in which we will delve deeper into topics that relate to recommendations raised in Professor Coaldrake’s report. These include:

- improving public sector culture

- managing consultants and contractors

- lobbying in the Queensland Government.

In the rest of this chapter, we focus on 3 areas we identified in our 2022–23 audit work with state entities that tie in with some of the observations made by Professor Coaldrake in his report.

Leadership changes

Effective leadership is instrumental in setting the strategic direction, tone, and culture of an entity and influencing an entity’s governance practices. When governance structures are re-organised, this can lead to changes in leadership. In our report, State entities 2021 (Report 14: 2021–22), we highlighted that when leaders change, it can have an impact on culture, re-aligning an entity’s values, behaviours, and internal controls.

Professor Coaldrake’s report states that frequent changes in leadership lead to uncertainty and confusion over an entity’s purpose and roles.

From 1 July 2018 to 31 January 2024, 8 departments had 3 or more changes in their directors-general (excluding times when acting while on holiday or short-term leave) as shown in Figure 5C. As our analysis extends beyond the announcement of the latest machinery of government changes, we have used the departmental names current from that date.

Notes:

- The department names used in this figure are those that came into effect following the machinery of government changes in December 2023, noting that many departments subject to machinery of government changes since July 2018 were renamed during that process.

- We deemed that a department was significantly impacted if major functions were transferred into that department. If a department only transferred functions out, or minor functions were transferred in (assessed by the number of employees or the value and nature of assets), we did not assess it as being significantly affected.

- The count of leadership changes is taken from the ‘Key management personnel’ note of the financial statements for each department or from information publicly available on the department’s website.

Queensland Audit Office.

While we recognise that changes to directors-general can be a by-product of machinery of government changes, of the 8 departments that had 3 or more changes, only 3 had been significantly affected by a machinery of government change.

The 5 remaining entities each play a key role in setting strategic direction, policy, and decision-making at a whole-of-government level. Two are central agencies.

The Coaldrake report specifically recommended fixed-term contracts of 5 years for directors-general, to ensure the success and stability of the leadership that governs the entity.

Frequent changes in leadership, particularly for those responsible for whole-of-government initiatives, make it hard for these departments to achieve and maintain momentum to plan and set the direction for the sector for the long term. It also makes it difficult for other entities to act on the plans and directions before another change in leadership delivers new and different initiatives.

Use of contractors and consultants

The Coaldrake report recommended that departments more robustly account for the benefits derived from engaging consultants and contractors, with regular monitoring by the Auditor-General. Implementing effective internal controls for procurement arrangements helps entities comply with relevant frameworks and achieve value for money. As noted earlier in this chapter, we often report issues in the procurement and management of these contracts.

Figure 5D shows that the total expenditure on contractors and consultants in departments has increased in recent years, from $1.9 billion in 2018–19 to $3 billion in 2022–23.

Queensland Audit Office.

Chief executives of departments are responsible for ensuring the procurement practices for their entity are cost-effective and achieve value-for-money outcomes. It is important for the state government to have confidence that this is achieved across all state entities, but to assess this across the sector can be complicated by entities classifying expenses differently. To allow for a more accurate and targeted analysis of contractor and consultancy spend at a whole-of-government level, a universal and consistent system for classifying expenditure would be beneficial, as recommended in our reports on Strategic procurement (Report 1: 2016–17) and more recently, Enhancing government procurement (Report 18: 2021–22). The former Department of Energy and Public Works and Queensland Treasury were working on this latest recommendation with consideration for existing and newly proposed financial systems.

Introducing a consistent approach could also help better inform state entities of their use of contractors and consultants, and be considered when assessing their in-house capability and capacity. This could also see a more coordinated approach when using contractors and consultants across the state sector, which could allow for state entities to negotiate better rates and lead to greater economies of scale.

Consultancy expenditure disclosures and discrepancies

Under the Annual report requirements for Queensland Government agencies, core departments and most statutory bodies (including universities) must disclose their expenditure on consultancies in their annual reports and on the Queensland Government Open Data Portal. The consultancy expenditure is broken down into categories relevant to each entity and should align with the entity’s financial statements.

During our 2022–23 audits, we identified differences in the amounts reported in financial statements to what was disclosed on Open Data – in several agencies.

The Office of the Chief Advisor guidelines for Engaging and managing contractors and consultants provides criteria around the definition of a service provider as a consultant. However, there is judgement involved in determining if the service provider work meets the definition of a ‘consultant’, based on the nature of the work they perform.

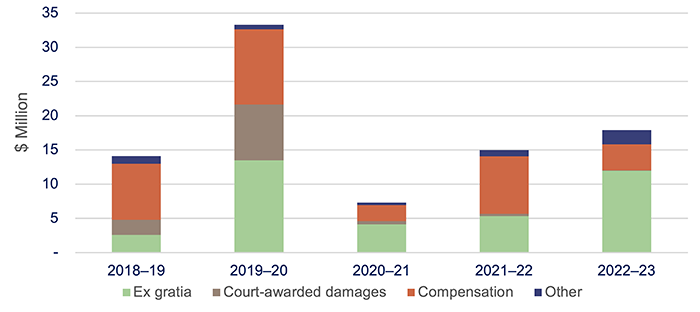

Special payments – including ex gratia payments

‘Special payments’ refer to payments that an entity is not contractually or legally obligated to make to other parties. For core departments, special payments include ex gratia payments, court awarded and out-of-court settlements, compensation, and general rates (paid to local government councils for social housing).

Ex gratia payments are often made using deeds of release (also called non-disclosure agreements). Professor Coaldrake highlighted the risks associated with these in his report, saying that those who raised concerns with non-disclosure agreements said that their effect was ‘deleterious’ (caused damage) to the workplace. Professor Coaldrake went on to say that it was an area that the Auditor-General might consider for periodic monitoring.

Under the Financial Reporting Requirements for Queensland Government Agencies published by Queensland Treasury, state entities are required to disclose the total amount for each class of special payments in their financial statements, and must include a description of the nature of special payments that are above $5,000.

Under the Financial Accountability Act 2009, special payments include ex gratia expenditure and other expenditure that is not under a contract.

Ex gratia expenditure is a payment that an entity is not legally required to make under a contract or otherwise.

Figure 5E shows the types of special payments made by large state entities over the last 5 years. On average, the former Department of Housing paid local governments $56 million each year in general rates so as not to disadvantage the councils by having social housing in their local government area. The department is not required to pay these types of rates under the Housing Act 2003, so the payments are classified as special payments. For the purposes of this analysis, we have excluded these from Figure 5E.

Note: For the purposes of this graph, state entities includes all departments, government owned corporations, hospital and health services, and large statutory bodies.

Queensland Audit Office from published entity financial statements.

There has been a 20 per cent increase in total special payments made by state entities in 2022–23 compared to the prior year.

Making ex gratia payments to executives

In 2022–23, we reported 3 significant deficiencies for one large statutory body and 2 government owned corporations relating to special payments made to their executives. This totalled around $792,000 in special payments made to 8 executives, including chief executives. We observed that each of these executives received payments that were made outside of the contractual obligations in their employment contracts and were agreed under non-disclosure agreements.

Making payments that sit outside the contractual obligations of an employment contract using non‑disclosure agreements can result in misuse and may expose state entities to reputational risks. Both Professor Coaldrake’s report and the Crime and Corruption Commission’s document entitled Use of non‑disclosure agreements – what are the corruption risks? raise concerns over the use of non-disclosure agreements, particularly in employee separation settlements. Non-disclosure agreements may be used to conceal suspected wrongdoing or make payments that are unjustified or excessive.

The issues we observed this year are consistent with those we reported in Transport 2021 (Report 10: 2021–22), where we identified 6 termination payments (with legal fees) at one entity totalling $1.5 million. We reported that there was no policy, guidelines, or board oversight to support these special payments, raising concerns for the propriety of decision-making.

Entities lack clear guidance for special payments

When reviewing these payments, we found no clear policies or guidance in place to outline:

- when these types of ex gratia payments are appropriate

- the basis for determining the appropriate amount paid

- who can approve them.

We also found instances where there was no written evidence to support the decision to make the ex gratia payments or approve them.

Without clear policies in place, and appropriate supporting documentation maintained, it may be difficult to justify payments made of this nature. Entities should also ensure that non-disclosure agreements are only used for legitimate purposes, and that sufficient supporting documentation is maintained to support the payment.

Queensland Treasury has specifically outlined in its Chief and Senior Executive Employment Arrangements policy, which applies to all government owned corporations, what payments executives are entitled to on termination. This policy does not explicitly allow for ex gratia payments to executives.

|

Recommendation 2 (all entities) Implement robust policies and procedures to ensure special payments are appropriate, defensible, and transparent. We recommend that all entities implement robust policies and procedures that specify when a special payment is appropriate and how it should be made. Guidance should outline who is authorised to approve special payments and what constitutes appropriate documentation to support:

|

|

Recommendation 3 (Queensland Treasury) Improve awareness and understanding of guidance material available for special payments, including ex gratia payments. We recommend that Queensland Treasury improves the awareness and understanding that all state entities have of guidance material available for special payments, including ex gratia payments. This should include:

|

Dashboards

Our interactive dashboard allows you to explore and compare information on government grants in Queensland by local government area and funding agency. It also includes extra information relevant to understanding the local context for specific grants.

Our interactive dashboard allows you to explore water entities’ financial performance, and view water storage levels, the number of dams, and drought declared areas.